Vaudeville in the United States

When hearing the phrase “Jewish women in vaudeville,” one is likely to think of the headliners Sophie Tucker, Belle Baker, and Fanny Brice. Some performers kept their Jewish identity offstage, such as Nan Halperin and Nora Bayes. Still to be added would be the visitors from other venues, such as Molly Picon, star of Yiddish theater, and Sarah Bernhardt, star of the stage. Enacted on the vaudeville stage was the emergence of the American Jewish woman. These women became representations of the dangers and emancipatory promises of assimilation. They represented divided attachments to both the Old World (the yiddishe mame) and the New (such as “Sadie Salome”). The reign of Jewish female vaudevillians ended in the 1930s, although their voices continue to be heard.

Introduction

When hearing or reading the phrase “Jewish women in vaudeville,” one is likely to think first of the headliners Sophie Tucker and Belle Baker, chief among those who placed their ethnicity at the center of their acts. (Fanny Brice might be added, although her early career focused more on the Ziegfeld Follies than on the vaudeville circuit per se.) One might also remember those headliners who were Jewish but kept their Jewish identity offstage, such as Nan Halperin and Nora Bayes. Still to be added would be the visitors from other venues, such as Molly Picon, star of Yiddish theater, and Sarah Bernhardt, star of the stage. But as rich as this list would be, it would introduce us only to the canonical history, the biographies of the familiar, established stars. It would only begin to tell the larger story of how and why Jewish women and vaudeville came to intersect as they did in the early decades of the twentieth century.

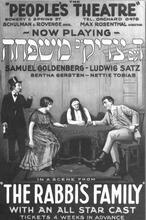

That story, first of all, included a much larger and more diverse company of participants. Generally left out of vaudeville histories have been the performers in Yiddish vaudeville, a circuit distinct from both the American vaudeville houses and Second Avenue’s Yiddish theater. In beer halls and saloons across New York City, such Jewish women as Nellie Casman, Miriam Kressyn, and Vera Rosanko performed sketches and skits mainly in Yiddish, identifying themselves more directly with yiddishkeit than did the performers of mainstream vaudeville. Equally unheralded have been the lesser-known performers on all the circuits—the second-billers, chorus girls, and female members of teams. One finds them mentioned in contemporary daily papers such as the New York Dramatic Mirror—performers such as Sadie Fields, Belle Gold, Annie Goldie, Leah Russell, Lillian Shaw, and Fannie Woods (Grossman 31). One finds recordings by singers such as Rhoda Bernard (“Yiddishe Matinee Girl” and “Rosie Rosenblatt”). For the most part, however, even their names have been lost, and their contributions elided from the histories.

This expanded list does not stop here, for participation in the business was not limited to performers. Behind the curtain were the Jewish mothers who supported both daughters and sons in the business, such as Sarah Glantz, Milton Berle’s mother and manager. And in front of the curtain were the Jewish women in the audience, constituting perhaps a third of the house in Jewish neighborhoods and areas such as Brooklyn.

Representation of Jewish Women in Vaudeville

What brought all of these performers and participants together is also a largely untold story—the story of a struggle over representation. Enacted on the vaudeville stage was the emergence of the American Jew. The Jews who played the central role in this process were the immigrants who had arrived from Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1910 and settled in the urban Northeast. During this period and in this area, an unprecedented intermingling of men and women from different races, ethnicities, and classes forged not only many of the expressive conventions of vaudeville, but also the foundations for representing ethnic American identity. The criteria for ethnic representation, particularly the representation of Jews, did not arise without debate. Many points of view entered the process, registering the attitudes of Jews of different generations and places of origin, of non-Jews, of men and women, of people from different social classes. Despite these differences, however, the debate was often pursued through a common frame of reference: the representation of the Jewish woman. Jewish women were drawn to the center of this debate on a number of levels: as participants in assimilation, as vehicles for the expression of attitudes about assimilation, and as speakers in their own right.

The figures of the yidishe mame and the ethnic vamp, the “dumb Dora” and the nagging wife served to express the anxieties and ambivalences attending assimilation in all its aspects, from the preservation of the community to the allocations of authority over issues of gender. The same process was at work in the celebration and vilification of the female Jewish vaudevillians themselves. That the battleground for these mixed feelings would be women’s bodies, specifically the construction and a spectacular display of those bodies on stage, is not surprising: Women’s bodies are often the site where cultural disputes are enacted. In this case, the focus on Jewish women’s bodies, in particular, is also not surprising. During this period, Jewish women did, of course, play a significant role in the process of assimilation, through their entry into the workplace (a workplace that included the vaudeville stage as well as the sweatshops), their exposure to new notions of sexual desire, and autonomy, and the reconfigurations of filial and personal responsibilities that accompanied these changes. But the actions and attitudes of the Jewish immigrant women themselves were rarely the focus of these debates. On the vaudeville stage, these women became representations of the enticements, dangers, and emancipatory promises of assimilation. One finds figures of Jewish women representing divided attachments to both the Old World (the yidishe mame invoked almost nightly in Sophie Tucker’s stage act) and the New (the ethnic vamp cajoled in Irving Berlin’s 1909 “Sadie Salome”).

Cultivating an American Jewish Identity Through Performance

Yet Jewish women did not allow themselves to be only the objects of this debate. They also entered the discussion as subjects in their own right. Female vaudeville performers, in particular, mainly recent immigrants and children of immigrants, found the vaudeville stage to be one of the few places where they could act out their concerns and dramatize their often divided feelings about both assimilation and their assigned roles as women. Through, and often against, the conventions of vaudeville, they fought to represent themselves, offering their own commentaries on the positioning of the Jewish woman in America. On a typical night on the stage, for instance, Sophie Tucker would follow a highly sentimentalized performance of “My Yiddishe Momme” with a highly sexualized performance of the ribald song “You’ve Got to See Mama Ev’ry Night.” She then complicated the picture further by drawing both personae together to create the fantastic figure of the Jewish “red hot mama.”

Such performances constituted not an abandonment of Jewish identity but rather an attempt to create something new: an American Jewish identity specifically available to women. The drive toward this identity is evident even in the performers’ names—or, rather, the name changes through which these women marked their transformation into performers. Sophie Tucker began her life as Sophie Abuza, adopted the name Tuck after her husband’s name, and then finally changed it to Tucker. Belle Baker began as Bella Becker, and Fanny Brice as Fanny Borach. While these changes to, or abandonments of, given names indicated the control that the women exerted over their professional lives in America, the new names hardly demonstrated the women’s desire to erase or hide their Jewish identity.

The beginnings of this struggle over representation can be traced back to the 1882 introduction of the first female “Hebrew” figure on the American vaudeville stage. The routine was titled “Our Pawnshop,” and it was performed by the male-female team of William Hines and Earle Remington. One might expect to find that the participation of Jewish women vaudevillians dated back to this early period. Yet many years passed before Jewish women began to appear on stage in vaudeville, and at least twenty years before a few of them began to acquire the status of headliners. Remington, for instance, although the writer of the team, was not Jewish.

This lag was partly the result of repressive attitudes toward women, and Jewish women in particular, that were as common onstage as off. Most of the early onstage “Hebrew” figures were male. In virtually all of the early routines about Jews, female characters were either absent altogether, as in such classic monologues as “Cohen at the Telephone” and “Levinsky at the Wedding,” or constructed only as offstage foils, as in the very first “Hebrew” routine, an 1878 number by the team of Burt and Leon entitled “The Widow Rosenbaum,” a parody of a popular Irish song. But if Jewish women themselves were largely excluded from the stage as vaudeville performers or subjects in their own right, the “Jewish woman” was not so difficult to find: nagging but voiceless, feared but powerless.

Sexism in Performance

This anxiety about women, and the containment of women, was evident in all levels of early performance conventions. It was present in the content of the routines, the extent and nature of the roles allotted to women performers, the positioning of the women on stage (alone and in relation to men), the wardrobe, the display of types of language and language proficiency, and the concrete dimensions of the voice itself. In addition, men were generally the ultimate curators and controllers of these conventions: the owners, managers, and booking agents, the fathers and husbands at home, and the men in the audience. Even the very appearance of women on stage was at first considered scandalous, a sign of public exposure that, in the case of the Jewish woman, amounted to nothing less than the woman casting aside her fidelity to her “people,” her “place.” Indeed, Jewish women were not encouraged to sing even offstage, and so had few models to draw upon as performers. In European Jewish society at the time, singers, both religious and secular, were invariably men, and America offered few models of its own (the remarkable burlesque performer Adah Isaacs Menken was one of the few exceptions).

Sexism was not the only obstacle to the opening of the stage to Jewish women. Whether male or female, Jews in general faced conflicting and constraining stereotypes of themselves as Jews, figures muffled in dialect and confounded by greed or incompetence, icons of ridicule and nostalgia. Jewish women during this early period were thus subject to a double negation, as women and as Jews.

Such denigration and displacement did not end with the new century. But it would be wrong to argue that these stage representations succeeded in wholly repressing Jewish women. Certainly, they did not keep Jewish women off the stage after the turn of the century, nor did they prevent these women from critiquing the representations themselves. One of the remarkable features of the Jewish female vaudevillians was their ability to claim cultural authority in such an inhospitable environment.

Female Autonomy and Fame

What made their entry onto the stage possible? A number of factors could be cited. Toward the end of the century, the vaudeville stage began to become “respectable,” largely through the efforts of performer and stage entrepreneur Tony Pastor. Pastor wanted to “clean up” vaudeville, to make it an arena of acceptable entertainment for women and families as well as men. Larger theaters were built to supplement the beer halls and cabarets, and certain risqué and male-directed conventions of the stage that had been common for fifty years began to change. Women performers were no longer represented in advertisements or on the stage itself merely as sources of illicit pleasure. At the same time, a female performer could respectably perform her own sexual desirability. By the second decade of the twentieth century, the effects of these changes could partly be measured by the makeup of the audience, which had been transformed from mostly men to roughly two-thirds men and one-third women and children.

Jewish women performers were now better able to enter the battleground of representation on their own terms. They could use their stage personae to explore their roles as women and particularly as Jewish women. Through the alterations of old routines and inventions of new ones, and through displays of visual and verbal dexterity, they articulated the intersections of Jewish and female identity, most notably with regard to their own previously suppressed sexual desires. Thus Sophie Tucker could become all things to all men—kept woman, nice Jewish girl, flippant flapper, beckoning Jewish mother—yet still manage to claim self-possession. (“I ain’t takin’ orders from no one,” she sang in a 1927 song.) While such flirtation with transgressive desire was occasionally criticized as “vulgar,” it was just as often celebrated as a sign of exuberant self-confidence. Indeed, in the theater columns of local newspapers, Tucker and others were granted a kind of “high society” status, their flamboyant show of sexuality and wealth reconfigured as a demonstration of refinement. Their every public gesture was loftily reported, from their appearances at public events to their displays of the latest fashions and their contributions to charities. Tucker was especially shrewd in coordinating the media’s presentation of her as the royalty of a now noble profession.

Not all female vaudevillians were as straightforward as Tucker in their use of their sexuality or as devoted to claiming class status as a sign of respectability. Performers such as Molly Picon and Fanny Brice explored more indirect avenues of self-expression and thus offered somewhat different commentaries on the positioning of Jewish women. Picon often played a young girl in man’s clothing, a performance recorded in the 1937 Yiddish film Yidl with a Fiddle, and Fanny Brice began developing her Baby Snooks character, a mischievous child undermining all sorts of authority, including her own. Nor were spectacle and indirection the only performative modes pursued by women in vaudeville; their acts also included material that directly addressed the kinds of experiences Jewish women encountered in America. In “The Song of the Sewing Machine,” for instance, Fanny Brice sang about her mother’s work in the garment district.

As is evident from these examples, the performance of gender and sexuality was only one sphere in which Jewish women explored their identity. In keeping with vaudeville conventions of the time, Jewish identity was also articulated through racial and ethnic impersonation. Such impersonations were wide-ranging in their choice of objects. Sophie Tucker began her career as a “coon shouter,” while Molly Picon first auditioned for vaudeville by impersonating a Hawaiian maiden, complete with short skirt and ukulele. Belle Baker was exemplary in this area. She might begin her act in the character of Sadie Cohen, an aging Jewish woman begging her boyfriend to marry her. Then she would sing another plea to a lover, only this time in minstrel-Italian dialect (“Come Back Antonio”). Then would come her version of “My Mother’s Rosary,” followed, perhaps, by a song with black minstrel overtones, such as “How I Wish I Could Sleep ’Til My Daddy Comes Home.” Finally, she would begin the song for which she became famous, “Eli, Eli,” sung entirely in Yiddish (Snyder 112).

Conclusion

While ethnic impersonation was not itself unusual on the early vaudeville stage, female performers were rarely involved. Aside from a few exceptional women such as Sophie Tucker, the blackface performers were men, in part because blackface operated as a mode of licensed transgression, a license deemed too dangerous to grant to women. But the female vaudevillians found ways around this prohibition. As in Belle Baker’s act, they performed through the personae of many ethnicities, even though ultimately anchoring their stage presence in their Jewishness. The meanings of such routines as enactments of Americanization were characteristically varied. The acts were sometimes a means of forging a hybrid American identity, born of the urban experience of the Northeast. They were also a means of displacing anxieties about the changing nature of Jewishness itself. In this latter case, one might argue that, by the second decade of the twentieth century, Jewish vaudevillians had begun to perform their own ethnicity on stage. Fanny Brice, for instance, did not know Yiddish when she began her career, but chose to learn it as a way of defining her stage persona. Finally, these routines were a way for Jewish women, in particular, to engage in the transgressions that such hybridity seemed to require. Baker’s modulating impersonations of a sexy Italian woman, a minstrel “coon,” a devout Catholic girl, and a Yiddish lover were a means of defining herself as an American Jewish woman, as was Fanny Brice’s self-naming “confession” in her hilarious “I’m an Indian.”

This struggle over the representation of the Jewish women did not end with the closing of the vaudeville houses in the 1930s. While the actual reign of the Jewish female vaudevillians ended about this time, many of the headliner performers continued to raise these issues in their acts in other venues. They also left a rich and varied legacy, as can be seen in the works of entertainers from Ethel Merman, who began her career at the end of the vaudeville era, to such contemporary figures as Bette Midler. Through them the voices of the Jewish vaudevillians continue to be heard, making their artful claims upon a still heatedly debated identity: the American Jewish woman.

Allen, Robert C. Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (1991).

Antelyes, Peter. “Red Hot Mamas: Bessie Smith, Sophie Tucker, and the Ethnic Maternal Voice in American Popular Song.” In Embodied Voices: Representing Female Vocality in Western Culture, edited by Leslie C. Dunn and Nancy A. Jones (1994).

Bial, Henry. Acting Jewish: Negotiating Ethnicity on the American Stage and Screen (2005).

Cohen, Sara Blacher, ed. From Hester Street to Hollywood: The Jewish-American Stage and Screen (1986); DiMeglio, Joe. Vaudeville, U.S.A. (1973).

Erenberg, Lewis. Stepping Out: New York Nightlife and the Transformation of American Culture, 1890–1930 (1981).

Gilbert, Douglas. American Vaudeville: Its Life and Times (1940).

Grossman, Barbara W. Funny Woman: The Life and Times of Fanny Brice (1991).

Isman, Felix. Weber and Fields (1924).

Kibler, M. Allison. Censoring Racial Ridicule: Irish, Jewish, and African American Struggles over Race and Representation, 1890-1930 (2015).

Laurie, Joe, Jr. Vaudeville: From the Honky-Tonks to the Palace (1953).

Matlaw, Myron, ed. American Popular Entertainment (1979).

Picon, Molly, with Jean Bergantini Grillo. Molly!: An Autobiography (1980).

Slide, Anthony. The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville (1994).

Slide, Anthony, ed. Selected Vaudeville Criticism (1988), and The Vaudevillians: A Dictionary of Vaudeville Performers (1981).

Smith, Bill. The Vaudevillians (1976).

Snyder, Robert W. The Voice of the City: Vaudeville and Popular Culture in New York (1989).

Staples, Shirley. Male-Female Comedy Teams in American Vaudeville, 1865–1932. Theater and Dramatic Studies 16 (1984).

Stein, Charles, ed. American Vaudeville as Seen by Its Contemporaries (1984).

Tucker, Sophie, with Dorothy Giles. Some of These Days: The Autobiography of Sophie Tucker (1945).

Wilmeth, Don B. Variety Entertainment and Outdoor Amusements: A Reference Guide (1982).