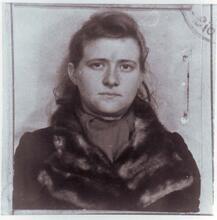

Reizia Cohen Klingberg

Reizia Cohen Klingberg began her career as a teacher, but when she began hearing reports of deportations and disappearances, she returned to occupied Krakow in 1942 and joined the ghetto’s underground movement. The group stole and smuggled weapons and engineered a Christmas Eve attack on German officers at cafes in downtown Krakow. Although the attack was successful, two members of the group betrayed the others, and they were all arrested, with Klingberg nearly executed on the spot for her part in the attack. She was sent first to Montelupich Prison and then to Auschwitz in January of 1943. Freed in 1945, she served as an interpreter for the Americans and British before making her way to Palestine in 1947, where she married and raised a family.

Early Life and German Occupation

Reizia Cohen Klingberg (alias Maria Kalina) was born on August 8, 1920, to Chava (1892–1943) and Menahem Mendel Klingberg (1890–1944), a member of a well-known Hasidic family in Krakow. She was the granddaughter of Rabbi Shem Klingberg (1873–1943). Her father, the chairman of Po’alei Agudat Israel, encouraged her to learn English and German. Prior to the German occupation of Krakow, she worked as a teacher in the Bais Ya’akov school in Tarnow.

After the Germans entered Krakow, but before the ghetto was sealed on March 20, 1941, Klingberg’s family left for the nearby town of Koszyce to avoid confinement in the ghetto. While in Koszyce, Klingberg ran a small school for Jewish children where she and her friends taught religious and secular subjects.

In 1942, the residents of Koszyce, which had hitherto been quiet, felt the danger increasing as news arrived of the transports being sent eastward and how those who were sent there were never heard from again. One of Klingberg’s friends sent her a letter via a Polish farmer at a nearby railway station, which read in part: “I am traveling to an unknown destination and I think my end is near.” Another friend, the mother of two children, wrote to her that her children were dying of starvation before her eyes. On the basis of this information Klingberg realized there was no hope left. Nothing remained but to fight; if she must die, she would die with honor.

Never a member of any youth movement, she decided to write to her friend Anka Balzam, a member of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir who then lived in Krakow, to enquire about underground groups. Within a short time, she received an answer that an underground group indeed existed. In September 1942, encountering no resistance from her parents, she traveled to Krakow to join the group.

Resistance Work

For Klingberg, who had never been inside a ghetto in her life, the difference was enormous. From the open spaces of the town and her warm, spacious home, she entered the walled-in ghetto with its narrow alleyways. Initially lacking all emotional, personal or ideological connection with the other members of the group, she was soon introduced to Laban (Avraham Leibovicz, 1917–1943), a member of the Dror youth movement and one of the commanders of the underground movement, He-Halutz ha-Lohem, whom she would later serve as his liaison. He-Halutz ha-Lohem united members of the various Zionist youth movements (Akiva A, Akiva B, Dror, Ha-Shomer ha-Dati, and several members of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir) into one group. Two other commanders, members of the Akiva youth movement, were Dolek Liebeskind (1912–1942) and Shimshon Draenger (1917–1943).

Given Klingberg’s status as an outsider who had had no connection with any specific movement, her membership in a Hasidic family in the city, and her lack of Zionist background, it is unclear why she was appointed Laban’s liaison. Her advantage for this position was probably her strongly Aryan appearance—blonde, tall, and pretty—which kept her free of suspicion by the Germans and Poles and gave her confidence and freedom of movement in her many travels at Laban’s orders within and outside the city.

Laban first explained the group’s goals to her. Since the attempt at saving had failed, only one option now remained—the preservation of Jewish honor, to be achieved by standing firmly and morally in the face of events unprecedented in human history. Despite the dangers involved, and fully aware of the fact that a number of her predecessors in the role of liaison had paid with their lives, Klingberg was prepared to take on any task.

In September 1942 the group decided to try the forest option. The PPR—Polska Partia Robotnieza (Polish Workers’ Party)—promised to assist them. The task of the couriers was to establish contact apartments that bordered on the Rzeszow forest region. The first attempt at cooperation with the PPR failed and in October a further attempt to operate independently in the forest also failed. As a result, the commanders of the organization concluded that the time was not ripe for operating in the forest and decided to concentrate their efforts in Krakow. Klingberg’s major task was to serve as liaison between Laban and his group outside the ghetto and members of the group inside the ghetto.

Weapons, so vital to sabotage activity, were taken from drunk Germans who were killed as they walked the streets of the city on Sunday nights, or by sending liaisons to supply sources in other places, such as Warsaw or villages in the district. Klingberg was among those delegated to participate in this activity.

The A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kevuzah established at 13 Jozefinska Street, in the apartment of the parents of one of the members, of necessity disbanded because the Jewish police, with the help of Jewish informers, almost caught Liebeskind. Most of the members moved outside the ghetto.

From now on, Klingberg went at Laban’s orders to the members who were scattered throughout the city. After the Aktion of October 27 and 28, 1942, in which seven thousand Jews were deported, most of them to the extermination camp of Belzec, the fighters decided they must quickly strike hard at the Germans, to undermine their confidence and avenge the loss of their loved ones. They also felt that the end of the ghetto was approaching.

They chose to attack close to Christmas Eve, on December 22. Their target would be the exclusive cafés downtown, whose clientele were the German officers and members of the administration. At 7:00 p.m., these places were crowded with German soldiers and officers.

Klingberg’s assignment was to report to Laban, who had returned to the headquarters on the Aryan side together with Dolek after giving orders to carry out the operation. He had also given handbills to the young women to distribute throughout the city, calling on the Poles to rebel against the Germans. Klingberg was to report on the comrades’ return to base early the next morning at an agreed-upon meeting place.

Arrest and Deportation

The operation was called Cyganeria after one of the targeted cafés. One member, Idek Lieber, threw grenades into the café, killing eleven Germans and wounding thirteen. All the members returned to base, but later it emerged that two members had turned traitor and divulged the hideout. At around 9:00 p.m. Gestapo officers surrounded and broke into the hut in which some of the members were hiding. They found twelve people inside. They chose Klingberg as the victim for their execution, making her stand with her face to a wall and aiming for the back of her neck. She stood unafraid, expecting a swift death, but was reprieved. She had managed to swallow the forged papers in her wallet. Arriving the following morning to find out why his liaison had not come to their meeting place, Laban was captured by the Gestapo, who had remained there, anticipating the arrival of more members. He was taken to the notorious Montelupich Prison, as his comrades had been the previous evening.

The women were separated from the men and taken to the nearby prison, formerly the Helzlaw monastery. Klingberg remained at the Montelupich Prison together with another comrade, Havke, because they were believed to be Aryan despite Klingberg’s assertion that she was Jewish and wished to join the others.

On January 28, 1943, Klingberg was sent to Auschwitz, where her supposed Aryanness did not protect her from hunger and diseases such as typhus. Yet despite her physical weakness, her spiritual strength was great. As the Russian army approached in January 1945, the women who remained on their feet were taken westward for forced labor in the war effort. The first station was a large camp in Germany, from which they had to march about six kilometers each way to the Telefunken ammunitions factory. They did not remain there long, but were taken west once more, deeper into the German interior. Everywhere they went, their stay was brief, as the Russians continued to advance. In the end, the Americans liberated them.

Postwar Life

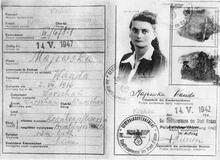

Klingberg worked briefly as an interpreter for the Americans and the British, thanks to the English and German she had learned as a child. Eventually she reached London, where she met Moshe Shertok and asked him to help her get to Palestine. On January 1, 1947, she reached Palestine by sea as part of Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah Dalet, traveling in the ship that was taking home the representatives of the first Zionist Congress held in Basel after the Holocaust.

Klingberg married Moshe Cohen (1916–1986); they had a son, Zvi (b. 1952), a daughter Chava (b. 1954), and six grandchildren. Her parents, her brother Yitzchak Isaac (1917–1944), and her sister Leah (1914–1943) perished in the Holocaust. On her liberation, she told her father’s spirit: “Father, you said the Germans would lose the war, though we would learn of it only in our graves. Yet we do not even have graves.” But while Klingberg had no graves at which to mourn her parents and siblings, she raised a family of her own, perhaps the best revenge of all.

Reizia Cohen Klingberg died in January 2006, in Tel Aviv, Israel.

Borwicz, Michal, Nella Rost, and Josef Wulf. W 3 Cia Rocznice Zaglady Ghetta w Krakowie (Polish). Krakow: 1946.

Interview with Klingberg, February 12, 1982, at the Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Oral Histories Department; Interview with Dr. Eichhorn, 1946. Archives of the Jewish Historical Committee of Krakow. Yad Vashem: 06/1740.

Peled, Yael (Margolin). Jewish Craców, 1939–1943: Resistance and Underground Struggle (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1993.

Rabban, Yehezkel (ed.). Know That I’m a Jew: The Life and Death of Avraham Leibovicz (Laban), a Commander of the Craców Ghetto (Hebrew).Tel Aviv: 1985.