Gertrude/Gego Goldschmidt

After escaping Nazi Germany in 1939, Gego (born Gertrude) Goldschmidt became one of Venezuela’s most creative and ingenious artists. She worked alone, using simple materials such as wire, stainless steel, and ropes, which gave her work a sense of “organic constructivism.” After becoming a Venezuelan citizen in 1952, she moved to Colombia, where she pursued work in watercolor, monotypes, and wood engravings. In the mid-1950s Gego began making art with great intensity, working as an engraver, sculptor, and draftsperson. In 1955 she had her first exhibition in the Galeria Gurlitz in Munich. Gego saw her work as a hybrid of local tradition, apparent in her humble materials and creative impulses. Throughout the 1970s, Gego also completed many integrated architectural sculptures for public and private clients.

Gego, born Gertrude Goldschmidt, was one of Venezuela’s most creative and ingenious artists. She worked alone, using simple materials such as wire, stainless steel, and ropes, which gave her work a sense of “organic constructivism.” Her sculptures have not only a sense of closure but also a boundlessness erasing any distance between viewer and artist and insisting on generating new perspectives. A personal sense of dislocation and instability deriving from Gego’s escape from Nazi Germany is perhaps indicated by the fact that critics see in her work a state of constant transience, disintegration, and reconfiguration. Pivotal junctures in her life and work reflect an appreciation of the immediate indigenous landscape, the economic-political views of global development and an aesthetic of exploration.

Early Life and Family

Gertrude Goldschmidt, the sixth of seven children, was born on August 1, 1912, in Hamburg and raised in a liberal Jewish family of bankers. Her father, Eduard Martin Goldschmidt, was born in Hamburg in 1868 and died in Los Angeles in 1956. Her mother, Elizabeth Hanne Adeline Dehn, also born in Hamburg, in 1875, died in Los Angeles in 1947. Gego studied architecture and engineering at the Technical University of Stuttgart and graduated in 1938. She was influenced by the innovations of the Bauhaus, a creative laboratory of design that operated for over two decades in pre-Hitler Germany. Goldschmidt’s family had fled to England after closing down the family bank which had been established in 1815 by Gego’s great-grandfather, J. Goldschmidt II. She herself finished her degree before her departure. Entrusted with the responsibility of liquidating the family’s belongings and throwing the keys to the family home into the river, she left Germany in 1939, a very difficult time for a Jew to try to leave, initially to go to England to join her family. Throughout her entire life she was silent about her personal life and escape from Nazi Germany. In fact, her artwork reflects an affirmation of life, finding both a metaphorical and literal path through linear and spatial webs.

Failing to obtain a resident visa in England, she proceeded to Venezuela, where she was granted an employment contract and was nicknamed Gego. In 1940 she met and married her Nuremberg-born husband, Ernst Gunz, with whom she worked on founding a lamp and furniture manufacturing company as well as preparing designs for architects. She had a son, Tomas (b. 1942), and a daughter, Barbara (b. 1944), with Ernst Gunz, whom she divorced in 1951. The next year, 1952, she met the sculptor, sketcher, graphic designer, painter, and publicist Gerd Leufert (1914–1998) and formed a lifelong relationship with him. After becoming a Venezuelan citizen in 1952, she moved to Tarma, Colombia, where she pursued work in watercolor, monotypes and wood engravings capturing the abundance and intricate designs of the tropical environment. In 1956 she returned to Caracas. Gego was an instructor at the College of Architecture and City Planning of the Universidad Central de Venezuela and at the Escuela de Artes Plasticas Cristobal Rojas in Caracas from 1960–1967, sharing her education and insights with many students. In 1959 she lived in the United States, participating in the Museum of Modern Art (New York) exhibition The Responsive Eye.

Art Career in the 1950s and 1960s

A military government existed in Venezuela from 1948 to 1958. However, the country’s oil boom of the mid–1950s coincided with and supported cosmopolitanism in the country. The Geometric/optical/kinetic art movement signaled an alignment of Latin America in general, and Venezuela in particular, with the avant-garde modernism of Europe and the United States. The involvement of artists and policy makers in modernism served the desarrollista (developmentists) of the economic elite and the government, while unfortunately bypassing the social reality of the majority of the population. Gego worked on the margins of the kinetic and op art movements, not going to Paris to work with such artists as Victor Vasarely (1908–1997), Antoine Pevsner (1886–1962) or Fernand Leger (1881–1955). She saw her work as a hybrid of local tradition, apparent in her humble materials and spatial meanderings and in her training and creative impulses. Art historian Rina Carvajal maintains that Gego’s work grew out of the skepticism and disenchantment of her wartime experiences, significantly dissenting from the optimistic and apologetic vision of the kinetic artists who were trying to emulate European rationalist and technological models.

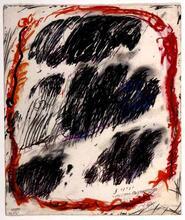

In the mid-1950s Gego began her art making with great intensity, working as an engraver, sculptor, and draftsperson. In 1955 she had her first exhibition in the Galeria Gurlitz in Munich, Germany. For Gego, the element of line describes the dualities of tension and order, of ambling mobility and patterned rhythm. In her first period of sculptures, from 1957 to 1972, structural systems use parallel lines, as if frozen in mid-air, allowing the viewer variant experiences when walking around the work. She experimented with aluminum, nylon, stainless steel, wire and neon. In 1961 she created aerial structures for the interior of Banco Industrial de Venezuela as well as working with architects on several large public sculptures. An example of work from the late 1960s and early 1970s is the outdoor sculpture Cinco Pantallas, constructed for the Instituto de Investigaciones Cientificas (IVIC) in Caracas. In 1959–1960 Gego and Leufert came to the United States, where he held a scholarship at Iowa State University. There she studied with the Argentinean Jewish artist/engraver, Mauricio Lasansky (b. 1919) and learned about iron techniques. In 1966 she experimented with line in printmaking at the Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles, California. The use of line in graphics is then transposed to wire-like threads in several pieces including Sin Titulo (1967), which alludes to unraveling cloth.

Scientific Influence

Borrowing from the scientific ideas of Stephen Jay Gould (1941–2002) and Niles Eldredge (b. 1943), which emerged in 1972, she transferred the description of the evolutionary pace of species (organic beings) to the stylistic evolution of an individual’s development, in this case, an artist’s stylistic development. Charles Darwin, the originator of the concept of “punctuated equilibrium” refers to the uneven pace of development, noting that a certain species can go unchanged for a very long time and is then replaced without any transition by a new species that looks like a variation of the old one. The scientific explanation is that a group of creatures separates from the main group and, through selection pressure, evolves fairly quickly and later spreads and replaces the parent species. Darwin, Gould and Eldredge, as scientists, are talking of time in 500,000-year segments, but art history as a discipline does not have that luxury. In fact, the condensation of ideas of punctuated equilibrium in art history is further abbreviated when looking at a single artist as a catalyst for a new style or way of manipulating the visual language of art. The scientific importance of the theory of punctuated equilibrium states that evolution is more likely to happen to small groups, isolated from the homogenizing effect of the larger main group. This scientific thought reinforces its utility in describing artistic innovation, which is so often an outcome of individual creativity. The differentiated and uneven evolutionary cadences of science are paralleled by the forced peripatetic path that Gego pursued, which geographically isolated her from her technical training and social, emotional and intellectual upbringing. The relevance of Gego’s adaptation can be seen in Reticulareas (1969), a groundbreaking room-size web of anodized aluminum and stainless steel lines of varying thicknesses forming a network of a transparency of volume through hanging geometric shapes such as triangles and squares that allude to a mangrove swamp, a fisherman’s net or a star map. The wire lines of the sculpture intertwined and repeated with no visible support resemble the spiny roots and branches of mangrove trees that dominate coastal towns like Tarma, Colombia or the outskirts of Caracas, Venezuela. At the age of fifty-seven, Gego distinguished herself in creating a unique aesthetic developed from diverse personal sources. She became a skilled craftsperson and designed systems of metal weaving that bypassed welding, enabling her to fully create her own pieces. Gego’s architectural training has seemingly invited her to work with the spatial aesthetics of openness and infinity. With line, Gego reflects a human scale and, as Carvajal notes, a “dimension of self.” Reticulareas is on permanent exhibition in the Galeria de Arte Nacional, Caracas.

Later Career

In 1970–1971, Gego created the following works, which incorporate the immediate environs of the tropics and the spatial flux of Caracas: Chorros (Streams), Malles (Meshes), Nubes (Clouds), Cuerdas (Strings or Cords), a planar aerial environmental bridge of suspended nylon and stainless steel strips for the Parque Central architectonic complex in Caracas, and Troncos (Trunks). Chorros appears as a vertical rain, a downpour of thin aluminum wires with subtle and broad metal twists changing the wire/current’s direction. The sculptures from the 1970s displace, replace and place the viewer in multiple structures, some bound to nature, others to a constructed reality, as in Sphere (1976). These pieces have been considered to be structural drawings subverting the grid and the rational structure of art. Line breathes, becoming intentionally unstable in its connections and orientations, indicating unforeseeable events that suddenly break with the linear, provoking discontinuities and revealing forces that generate a life energy in the form, according to Carvajal. This description has immediate relevance to seeing line as a sign/indicator of Gego’s personal (Holocaust) history of escape, exile and life-long artistic innovation. These pieces offer a type of coexistence within all her media—no distinction between graphics, two or three dimensional sculpture and drawing. Throughout the 1970s, Gego also completed many integrated architectural sculptures for public and private clients.

Carvajal sees a symbiosis between movement and stasis in the intimate Drawings without Paper of the early and mid 1980s; they resemble scratchy calligraphic signatures, broken bed springs, torn window screens and knotted hair pulled from a hair brush. Her subjective references increase in the 1980s and 1990s with works such as bichos (animals/creatures), cuadriculas dislocadas (dislocated grids) and tejeduras (weavings). Many of the pieces from Drawing without Paper are craggy lines of wire alluding to the barren branches of trees floating in space in a German winter, a broken wire fence and, in other pieces, barbed wire. Her work became playful, using recycled industrial waste materials and metals, loosening the regularity of repetitive modules and grid-like formations. The privilege of age provided Gego with the opportunity to emphasize the ambiguous in her work and combine the fragile with the permanent, forming an embracing transparency.

Gego died in Caracas on September 17, 1994.

Art Nexus, The Nexus Between Latin America and the Rest of the World. Miami, Florida and Bogota, Colombia: 1991–2003.

Barnitz, Jacqueline. Twentieth Century Art of Latin America. Austin, Texas: 2001.

Biller, Geraldine P. (guest curator). Latin American Women Artists, 1915–1995. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: 1996.

Bois, Yve-Alain, and Paulo Herkenhoff, Ariel Jimenez, Luis Enrique Perez Oramas, Mary Schneider. Geometric Abstraction; Latin American Art from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection. Caracas, Venezuela: 2001.

Carvajal, Rina, and Alma Ruiz. The Experimental Exercise of Freedom. Los Angeles: 1999, 111–136.

Guevara, Roberto, Gego..

Mosqrera, Gerardo, ed. Beyond the Fantastic: Contemporary Art Criticism from Latin America. London: 1995.

Pantin, Yolanda. Gego Works on Paper, 1962–1991. Caracas, Venezuela: 2002.

Peruga, Iris, and Marta Liano. Gego 1955–1990: A Selection. Caracas, Venezuela: 2002.

Rasmussen, Waldo, (organizer). Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century. New York: 1993.

Sullivan, Edward, ed. Latin American Art in the Twentieth Century. London: 1996.

www.cs.colorado.edu Speciation by Punctuated Equilibrium.

De Zegher, M. Catherine, ed. Inside the Visible: An Elliptical Traverse of Twentieth-Century Art In, Of and From the Feminine. Cambridge, MA: 1993.