Responses to Skipwith v. New York City Board of Education

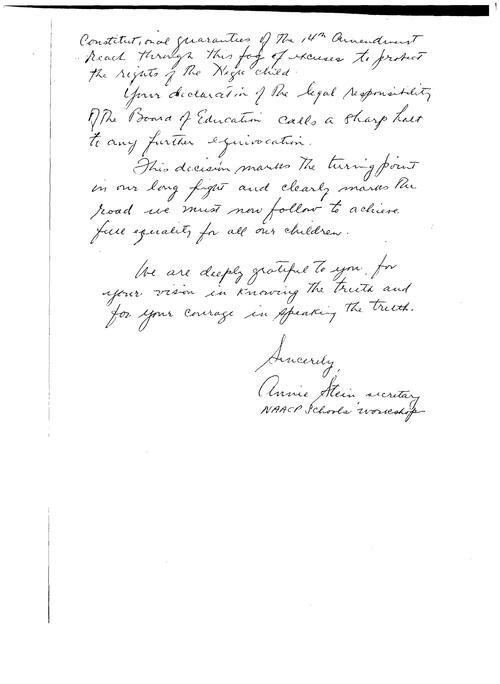

Letter to Justine Wise Polier from Annie Stein, December 23, 1958

Letter To Justine Wise Polier From Annie Stein, December 23, 1958, page 1

Letter To Justine Wise Polier From Annie Stein, December 23, 1958, page 1.

Courtesy of Eleanor Stein.

Discussion Questions

- Initial assessment/review: Who wrote this letter? When? For what purpose and what audience?

- Based on her letter, what is Annie Stein's point of view on the Skipwith decision?

- Stein talks about the difference between moral responsibility and legal responsibility in her letter. How are these responsibilities different? Which was the Board of Education missing in her mind? How did this allow them to get around making change? Do you think moral responsibility or legal responsibility is more powerful? Why?

- What did you learn about Annie Stein's background from the document? How, if at all, do you think this background might have informed her point of view? What else do you wish you knew about her?

"Wasting Time"

Another Angle column

Wasting Time

By James L. Hicks

…Last September several courageous Harlem mothers became fed up with paying teachers to warp the brains of their children, and flatly refused to send them to two of these inferior schools…

Once in the courts the mothers and their lawyers conclusively proved what we have been saying, that what they have been saying – that the Board of Education through its school administration, does discriminate against Negro and Puerto Rican children by refusing to give them an adequate supply of good permanent teachers, denying them the facilities afforded white students in so-called white schools and by conducting the Harlem schools in such a manner that the Negro and Puerto Rican child receives not only an inferior education but an inferiority complex as well…

In many respects in this case the New York Board of Education presents a much more bigoted attitude than many of the bigoted white boards of education in the South.

For in the South today even the bigots have accepted the fact that “separate but equal facilities” is a myth (and therefore unconstitutional) and today they are simply waging an all-out fight against integration.

But while Southern bigots have given up on separate but equal long ago, the New York Board is just getting around to losing a fight on the already outlawed doctrine. And despite its loss, it is at this late date considering appealing that loss to a higher court.

The Board thus finds itself belatedly trying to do what the bigots of the South have already found it impossible to do – to find a legal way to commit an illegal act with taxpayers’ money. …

James Hicks, "Wasting Time," Amsterdam News, (New York City, NY.) 3 January 1959.

Discussion Questions

- Initial assessment/review: Who wrote this article? When? For what purpose and what audience?

- Based on what you've read, what is his point of view on the Skipwith decision? What matters to him about this case?

- Based on what you know from his article, why does Hicks think that the situation is worse in the North than in the South? Do you agree or disagree with Hicks? Why?

- What do you think the experience of segregation meant to the people who lived in the North and the South? How do you think the lives of African Americans were different?

- What did you learn about James L. Hicks' background from the document and/or from additional reading? How, if at all do you think this background might have informed his point of view? What else do you wish you knew about him?

Letter from Mrs. L.O.K to Justine Wise Polier

Apr. 10, 1959

Judge Justine Wise Polier

Children's Court Division

Domestic Relations Court

New York City.

Dear Judge Polier:

In your article in the U.S. News of Jan. 9, 1959, you state that the best teachers in New York City are being allowed to choose their schools, and that the Negro and Puerto Rican schools are being assigned the weakest teachers.

As a former teacher in the Indianapolis Public schools, as the manager for ten years of 11 units of Negro property and as the wife of an architect who built Negro housing in Indiana, I should like to answer your complaint.

A huge percentage of the Negro pupils now in Northern schools, have come from the South, where segregation has existed for generations. Finding themselves in an integrated society, these formerly stable children, become arrogant and abusive; in other words, they go "haywire". Unfortunately, welfare workers, police and school principals have not cracked down sufficiently on these delinquents. (Could such laxness be due to fear of political retaliation?)

I know definitely of cases where Negro children have kicked, cursed and even threatened women teachers with physical assault; but it does these teachers no good to protest to their principals, for in many cases the principals merely say, "Settle these matters yourself." These teachers feel that they cannot do a good job of teaching under such circumstances; and I, as a former teacher, admire them for refusing to accept positions in Negro neighborhoods. If the Negro parents want better teachers for his neighborhood school, let him discipline his children, but the average Negro parent is apt to cry "Discrimination!" if his children are disciplined. And, I might add, runs to the NAACP with his story.

A stiff backed attitude by society in general would help immensely; for, after all, the whites have some rights, which are now ignored by welfare, church and judiciary groups.

I am particularly bitter today, because I have recently heard from two schools of Negro boys pushing white girls up against walls and fences and passing their hands over their bodies. What is the matter with the old fashioned whipping post?

In Cleveland, O., where I lived for nine years, there was no trouble with Chinese children; is there any reason why the Negro race cannot control its offspring?

As a result of my numerous contacts with Negroes, and as a result of Negro studies while living in four large cities, I am for Segregation with a capital S.

Yours. truly

[Signature]

(Mrs. L.O.) H.V.K.

[name & address redacted]

Indianapolis

Ind.

(Mrs. L.O.) H.V.K to Justice Justine Wise Polier, 10 April 1959, Polier, Justine Wise, 1903-1987. Papers, 1892-1990, Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliff College.

Letter from Justine Wise Polier to Mrs. LOK

May 11, 1959

Mrs. L.O.K

[name and address redacted]

Indianapolis, Ind.

Dear Mrs. K:

I received your letter concerning the report on a decision that I rendered.

My experience throughout over 23 years on the Bench has convinced me that as one comes to know people one cannot put any group in a separate category; that every religious, racial and national group has human beings of every variety among it. The task of America, which is a difficult one, is to evoke the best in each individual so that he or she can become educated in accordance with his ability and make the fullest use of his or her potential.

Certainly the American and religious tradition that all human beings are the children of God and brothers places a heavy obligation on those of us who believe in that ideal to work towards the abolition of the discrimination in our actions and the prejudice in our hearts which is so destructive to not only those who are subjected to it but to those who practice it.

With every good wish,

Sincerely,

Justine Wise Polier

JWP:mo

Justice Justine Wise Polier to (Mrs. L.O.) H.V.K, 10 April 1959, Polier, Justine Wise, 1903-1987. Papers, 1892-1990, Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliff College.

Discussion Questions

- Initial assessment/review: Who wrote these letters? When? For what purpose and what audience?

- What are Mrs. L.O.K.'s arguments against integration of schools? What solutions does she suggest?

- What did you learn about Mrs. K.'s background from letter? How do you think her background informed her point of view? What else do you wish you knew about her?

- What is the difference between how Judge Polier views "people" and how Mrs.K. views "people?" How is this difference significant to this case and civil rights in general?

- What did you learn about Judge Polier's background from her letter? How do you think her background informed her point of view in writing this letter? Do you think it also informed the way she ruled in the Skipwith case? If yes, do you think a judge should only take the law and facts in a case into account when making a ruling or should they take other things into account as well?