Jewish Women's Archive

Founded in 1995, the Jewish Women’s Archive (JWA) was established on the premise that the history of Jewish women—both celebrated and unheralded—must be considered systematically and creatively in order to produce a more meaningful historical record. From the beginning, it believed that access to the stories and achievement of historical role models would transform the way contemporary Jewish women of all generations contemplate their own stories and their ability to respond to the challenges of their own moment. In the 1990s, JWA pioneered the use of digital tools in the creation of an archive for the twenty-first century. It has engaged in extensive educational outreach programs, pioneered inclusive oral history, effectively used social media to engage countless users, and responded to local, national, and global crises.

Origins

Founded in 1995 on the premise that the history of Jewish women—celebrated and unheralded alike—must be considered systematically and creatively in order to produce a more meaningful historical record, the Jewish Women's Archive’s founding mission was “to uncover, chronicle and transmit the rich legacy of Jewish women and their contributions to our families and communities, to our people and our world.” An update of the mission statement in 2013 declared that “The Jewish Women’s Archive documents Jewish women’s stories, elevates their voices, and inspires them to be agents of change.” The updated statement made explicit a hope that was already implicit in JWA’s early iterations: that access to the stories and achievements of historical role models would transform the way contemporary Jewish women of all generations contemplate their own stories and their ability to respond to the challenges of their own moment. As JWA celebrates its twenty-fifth anniversary in 2021, that reformulated mission seems more apt than ever.

While Jewish women have always played crucial roles in the cultivation and continuity of their communities, their efforts typically went undocumented, buried within an historical record that privileged men’s stories and accomplishments. Much source material on Jewish women was discarded or, when it was saved, was catalogued within the collections of husbands and fathers (on at least one notable occasion, in a file labeled “miscellaneous”). Even in fields open to the importance of women’s experiences, for instance in the field of American history, the tendency to disregard the Jewish identity of many prominent women often rendered their Jewishness invisible. Throughout its existence, the Jewish Women’s Archive has insisted on the importance of Jewish women’s historical legacies and the need to make those legacies visible and accessible, developing unique and innovative tools and programs with which to do so.

An important origin story can be traced to the attendance by JWA’s founder, Gail Twersky Reimer (b. 1950) at a Jewish Funders’ Conference in 1995, where attendees were asked to read a powerful recent essay by Leonard Fein, a noted Jewish social justice thought leader and activist. Reimer asked Fein if he realized that his list of inspiring historical exemplars failed to include a single woman. According to Reimer, Fein responded by asking “where would I go to find out about such women?” In Reimer’s mind, that was the moment that cemented her commitment to an idea she had been developing that would soon become the Jewish Women’s Archive.

Another important motivation for Reimer related to the massive effort being made at the time to document the destruction of European Jewry, through oral history projects and the recently dedicated United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Although Reimer was herself the daughter of survivors, she could not help but believe that the level of resources being devoted to documenting the ultimate assault upon Jews and the Jewish community should be complemented by dedicated efforts to capture the creativity and contributions that went into building a living and vibrant American Jewish community.

Reimer, who holds a Ph.D. in English literature, had already been contemplating the importance of bringing the lens of women’s experience to Jewish experience. Along with a faculty position at Wellesley College and work for the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities, Reimer had co-edited two books focused on women’s readings of Biblical texts and Jewish liturgies. Determined to turn her attention to historical experience, she began to convene conversations and reach out for funding for a new kind of public history effort that would focus on excavating and sharing the rich experience and contributions of Jewish women, with an initial focus on the American experience.

Early Work

Pre-eminent Jewish feminist philanthropist Barbara Dobkin credits her grandmother, the neighborhood “key-holder” for the Jewish National Fund zedakah boxes, for instilling in her a life-long passion for large-scale giving to the global Jewish community. Co-founder of MA’YAN: The Jewish Women’s Project and former chair of The Jewish Women’s Archive, Dobkin has established and funded numerous projects that seek to raise the status of Jewish women and build the self-esteem of Jewish women and girls.

Photographer: Joan Roth.

The new organization arrived at a time when attention to women’s history and women within Jewish Studies was growing. Other concurrent initiatives included the 1997 publication of the groundbreaking encyclopedia, Jewish Women in America, and the emergence of accomplished scholars in the fields of Jewish Studies and Women’s History. Many of these scholars, led by Brandeis historian Joyce Antler, joined JWA’s Academic Advisory Council, a group that continues to support and guide JWA in developing directions for historical inquiry and that contributes to the organization’s varied ambitious projects. Important funders in both the Jewish and non-Jewish communities, including the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Dorot Foundation, the Charles H. Revson Foundation, and the Covenant Foundation, also recognized the significance of JWA’s mission and supported the new project, as did an impressive group of activists, philanthropists, and communal leaders who joined JWA’s founding board, chaired by Barbara Dobkin.

Created during the period of the Internet’s rapid expansion in the 1990s and presciently seizing on its promise, the Jewish Women’s Archive pioneered the use of digital tools in the creation of an archive for the twenty-first century. Responding to the changing use of libraries and physical archives, JWA invited researchers and students to find and use information in new and creative ways through powerful search engines and multimedia exhibits; it provided searchers of the web with ready access to primary sources previously available only to scholars and a growing profusion of trustworthy information on the history of American Jewish women. JWA’s first major undertaking, the Virtual Archive (pre-Google), provided a portal database to significant holdings on Jewish women in United States and Canadian repositories, allowing researchers to locate materials for analysis in the context of related records.

The earliest JWA content focused on the stories of both prominent Jewish women and those whose stories were less likely to be preserved. The Women of Valor project (initiated in 1996 in collaboration with Ma’yan: The Jewish Women’s Project) highlighted the life stories and accomplishments of eighteen women. It began with three posters—suitable for hanging in schools, synagogues, camps, and Jewish community centers—depicting Glückel of Hameln, Rose Schneiderman, and Henrietta Szold and gradually expanded to include curricular materials and richly detailed web-friendly online exhibits. Other than Glückel, a seventeenth-century German-Jewish businesswoman, the Women of Valor were North American women in various areas of achievement, from religion, to sports, to business, to science. Through this project, JWA sought to make these vital stories accessible, whether on the wall of a classroom or available via the internet to users of every age.

Pioneering Inclusive Oral History

JWA also set out to model an inclusive approach to history, one that could go beyond notable women who already had a place in history books. Concerned with how to collect and present the experience of ordinary people, who lacked the written records that would be of interest to physical archives, JWA incorporated oral history into several of its early programs. An initial pilot effort in cooperation with Temple Israel of Boston expanded into community-led projects in Baltimore and Seattle, capturing the stories of 30 women over the age of 80 in each city. This Weaving Women’s Words project culminated in ambitious exhibits at the Seattle Museum of History and Industry and the Jewish Museum of Maryland. Both exhibits highlighted the local oral histories and featured beautiful photographs of each woman by photographer Joan Roth. The Baltimore exhibit, in addition, featured artwork commissioned from 30 different Jewish women artists to honor and depict each narrator’s story.

Building on the expertise developed through these oral history projects, JWA in 2005 published In Our Own Voices, a how-to guide for conducting life history interviews with American Jewish women. Designed for use by individuals and community groups, the guide invites readers to become “makers of history” by using oral history to capture and preserve the stories of their mothers and grandmothers, teachers and colleagues, community members and friends.

In a further demonstration of the importance of creating inclusive historical records, the Jewish Women’s Archive launched its first oral history project that included equal representation of men’s and women’s stories in the aftermath of 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. Initiated as a collaborative project with the Institute for Southern Jewish Life in 2006, the Katrina’s Jewish Voices project (KJV) collected oral histories from 85 Jewish narrators impacted by Katrina. As JWA’s first online collecting project, KJV also used interactive online tools to gather stories, images, and reflections about the New Orleans and Gulf Coast Jewish communities before and after Hurricane Katrina, from people who had personal testimony and artifacts to share.

Continuing to pioneer the use of oral history in gathering individual and collective stories, in 2019, JWA premiered Story Aperture, an online app that encourages story-gathering and enables easy recording that can be immediately shared with JWA. JWA provides detailed guides to collecting and sharing these recordings, as well as a number of question sets focusing on topics that include voting, COVID-19, and building families that don’t fit conventional heterosexual-two parents-and-kids paradigms. Story Aperture is positioned to respond to emerging communal questions and challenges; one question set focuses on seeking stories from Jews of Color, another on “Archiving #MeToo.”

350 Years of American Jewish Women’s History

In 2004/2005, the American Jewish community commemorated the 350th anniversary of Jewish communal presence in what became the United States. Although many national efforts fell short of sufficiently recognizing women’s place in that story, a more inclusive story did advance as JWA challenged male-centered narratives and took a leading role in a joint effort by multiple museums and archives to create a national commemoration. In addition, JWA created numerous signature programs of its own to mark this milestone. This Week in History, an ongoing effort first introduced during the 350th, connected movements and individuals with specific dates on the calendar, enabling JWA to expand the stories, individuals, and events on its website while highlighting the impact of women’s stories throughout the year. Additional efforts included public exhibits, a film series, a reading series, a timeline of American Jewish history focused on major events for women, and a printed curriculum highlighting women’s role in the community’s 350-year history. JWA, working with Lions of Judah (a women’s philanthropy arm of the Jewish Federations of North America), also organized a gathering in Washington, D.C., with sixteen Jewish women of notable historic achievement, including pioneering rabbis, politicians, artists, communal leaders, and activists. The Library of Congress event featured a speech by Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who shared a moving appreciation of what the example of Henrietta Szold meant to her. Ginsburg also referred to the experience of her own mother as she posed a question that illuminates the promise the American experience has offered to many of its immigrants and citizens: “What is the difference between a New York City garment district bookkeeper and a Supreme Court Justice?” Her answer: “One generation.”

Exhibits, Curricula, and Other Resources

In 2005, JWA took on the important story of American second-wave feminism, a movement in which Jewish women played an almost dominant role as thought leaders and activists even though historians had paid little attention to this aspect of their identity. To create The Feminist Revolution exhibit, JWA asked an array of pioneers within both American and Jewish feminism to share a historical artifact documenting their activism, along with a personal statement contextualizing the significance of the item they chose.

Like all of its programs, JWA’s educational offerings have multiplied and deepened over time, emphasizing rich resources, analysis, and accessibility. Building on the Women of Valor online exhibits and posters, JWA developed a broad array of online curricular materials. A variety of lesson plans provide educators with both content and pedagogical approaches. For example, JWA’s Living the Legacy lesson plans, created in 2011, offer extensive curricular material to scaffold teaching about the role of Jews, female and male, in the American civil rights and labor movements. These plans, like others on the site, offer framing essays, primary sources, and fully imagined class activities. Lesson plans also help teachers show students how to work with the primary sources. In 2006, JWA began running an Institute for Educators, run regularly from 2006 to 2013, that offered teachers a cohort-based immersive introduction to JWA’s resources. More recently, JWA has provided online seminars with the same goal of helping teachers present themes in Jewish women’s history, examine primary source documents and oral histories, explore multimedia resources, and develop strategies for using these materials with students.

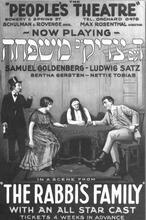

In 2006, JWA introduced a blog, originally called Jewesses with Attitude and relaunched in 2017 as Jewish Women Amplified. In 2007, JWA turned to documentary film as another vehicle for storytelling, highlighting Jewish female entertainers whose achievements often go unrecognized. The award-winning Making Trouble profiles the struggles and successes of Molly Picon, Fanny Brice, Sophie Tucker, Joan Rivers, Gilda Radner, and Wendy Wasserstein.

A major addition to JWA’s resources came in 2009, when Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, edited by Paula Hyman and Dalia Ofer, found a home on the JWA website, thus for the first time offering extensive resources about women outside of North America on the JWA website. The Encyclopedia had originally been published on CD-ROM by Shalvi Publishing Ltd in cooperation with JWA. Its addition to the website made JWA host to the largest collection of well-researched and thoroughly vetted material about Jewish women available anywhere. A new edition, renamed the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, with hundreds of revised articles and new entries, was released in 2021.

Change in Leadership

In 2014, Gail Reimer retired, amid a year punctuated by celebrations of the eighteenth anniversary of JWA’s founding and Reimer’s leadership. One of the other notable innovations of that year was a Boston-area pilot iteration of the Rising Voices Fellowship, offering female-identified high school students a highly supportive leadership cohort experience focused on developing writing skills, refined through a feminist, Jewish, social justice lens; the fellows’ writing is published on the JWA blog and elsewhere, through syndication partnerships.

With Reimer’s retirement, leadership passed to an academically trained historian with a long history at JWA. Judith Rosenbaum (b. 1973) began working at JWA in 2000, while still a graduate student. She continued in varied capacities, including as Director of Education and Director of Public History, before succeeding Reimer as executive director. In keeping with broader trends toward elevating the profile of women’s leadership, Rosenbaum took the title of CEO in 2019. Rosenbaum’s leadership represented a meaningful passing from generation to generation in more ways than one. She grew up identifying as a Jewish feminist under the influence of her mother, Yale historian Paula Hyman. Hyman’s pioneering work in Jewish women’s history was key to so many of the major efforts that made JWA possible [see, e.g. her role as co-author, with Sonya Michel and Charlotte Baum, of The Jewish Woman in America (1976) or her work as co-editor (with Deborah Dash Moore) of Jewish Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia (1997) and (with Dalia Ofer) the Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia (2009)].

Under Rosenbaum’s leadership, JWA continued to enrich and broaden its online content while also building upon existing communication outlets and the growing world of social media to expand JWA’s engagement with ongoing public conversations. Her early years at the helm saw projects that had been in the pipeline for years, like the Women Rabbis oral history collecting project (a project of Jewish Women’s Theater, now known as The Braid), come into public view on the Archive’s website. Additional significant initiatives included the JWA Book Club, a regular podcast “Can We Talk?,” and many projects associated with the Story Aperture app.

Responding to Crises

Showing how and why the stories of both prominent and “ordinary” Jewish women matter became increasingly urgent as challenges to the United States as a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-faith, multi-gendered society emerged (too often, violently) during the Trump administration. In response, JWA rededicated itself to finding examples of resilience and resistance in the public and private histories of Jewish women and showing how many built upon their outsider status to challenge and navigate oppressive institutions. The pursuit of social change became a more explicit aspect of JWA’s programs. As the Rising Voices Fellowship expanded into a robust national program (having engaged more than 100 teenagers by 2020, representing a diverse array of religious, ethnic, racial, and geographic backgrounds), these strong young voices powered important critiques, published on the JWA blog and beyond, of many of the familiar practices and assumptions shaping both the American Jewish community and the broader society.

JWA had always striven to be ahead of the curve in building upon the possibilities engendered by advancing virtual technologies. Yet even with the advent of social media, it had generally stuck to the notion that most users would engage with the Archive as consumers of the information offered on the website, with less interaction in real time outside of in-person programming. The challenges of the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020 and 2021 called forth a different response, enabling JWA to connect with its audience in a new and promising fashion. In March 2020, JWA introduced the Quarantine Book Club, showcasing engaging authors through regular Thursday evening programs. These weekly programs quickly expanded into on-line history courses engaging issues of activism, leadership, navigating crisis and change, and race and ethnicity. Finding an eager audience, these book conversations (soon redubbed the “Quarantine(ish) Book Talks”) and historical discussions continued past the pandemic. Thousands of subscribers from around the world signed up, with a typical evening drawing between 250 and 500 participants and many more accessing the taped programs in subsequent weeks. These lively conversations, moderated by Rosenbaum in full force as historian, careful reader, and engaged interlocutor, created an unprecedented sense of virtual community among old and new followers of JWA, in a fashion that would have been impossible to imagine twenty-five years before.

Future

Indeed, as the Archive moved toward a twenty-fifth anniversary celebration of its work in 2021, its impact could be discerned in religious schools, college classrooms, family celebrations, online conversations, and published scholarship. JWA achieved its early goals not only of becoming the premiere site for the sharing and growth of Jewish women’s history, but of shifting the discourse on the nature of Jewish history. In fact, in so many ways, it has become what Gail Reimer initially called for in her 1995 speech at the Jewish Funders Network when she challenged Jewish communal donors and leaders to imagine the possibility of “a central address [to] easily access material on immigrant women, on Jewish women and social action…. a prestigious address that made this material so readily accessible that ignoring it would only be considered ignorance, at best, and malevolence, at worst …. If there were an institution on the scale of the Holocaust Museum which rather than ensuring that we not forget, was designed to ensure that we re-member the forgotten half of Jewish experience - the experience of Jewish women - could anyone, anymore, plead innocence?”

If JWA does not rival the scale of the Holocaust museum, it has ensured that it is long past the day when anyone could justify focusing only on men as exemplars in American Jewish history with the excuse that there was nowhere to go for information on the women.