Community Organizing II: Wednesdays in Mississippi

Encounter a little known story of women collaborating across geographic, racial, and religious boundaries through documentary clips of Wednesdays in Mississippi activists.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

- The Civil Rights Movement consisted of various models of community organizing and social change, carried out by a range of activists from different generations, geographic areas, races, and faith backgrounds – and there is much to be learned from these different models and activists.

Essential Questions

- What different kinds of activism took place during the Civil Rights Movement?

- How did older and younger activists relate to one another?

Materials Required

- Copies of Community Organizing Chart

- Copies of Letter from a Parent (to Vivian Rothstein)

- Video clips from Wednesdays in Mississippi Documentary

- Copies of Wednesdays in Mississippi Documents

Wednesdays in Mississippi: Introductory Essay

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy, Civil Rights, Unit 2, Lesson 5

If some parents disapproved of their children's involvement in civil rights activism, others were inspired by their children to take greater action themselves. One such parent was Polly Cowan, mother of Freedom Summer volunteers Paul and Geoff Cowan. Polly was herself a committed civil rights activist, who brought her Jewish social justice sensibilities to her work as a volunteer for the National Council of Negro Women, where she worked closely with its director, Dr. Dorothy Height. She and Height were particularly interested in ways to encourage women's participation in the civil rights movement and to protect female activists who were being mistreated by police and jail officials.

When her sons volunteered to join Freedom Summer, Polly was both concerned with how the media was portraying the student activists and inspired to create a program that would support and build on the foundation they were creating. As Dorothy Height recalled, when Polly Cowan heard about Freedom Summer, she wrote to Height and said, "My children are going, and I know there are other women who'd want to kind of be there to support their children and to let it be known that we are responsible people." She and Height were also concerned that the increased activism of Freedom Summer would intensify the brutal treatment of female civil rights workers. So they developed their own model of community organizing in a project called "Wednesdays in Mississippi" that brought together women across boundaries of race, religion, and geography (though most of the women in their project were more homogenous in terms of class, education, and community position – what Cowan called the "Cadillac crowd") to support and educate one another. They understood that women in southern communities would play important roles in sustaining civil rights work when Freedom Summer was over and that northern women could help report on conditions in the South and perhaps bring some attention to civil rights issues in their own communities. They believed that women working together could overcome some of the differences that divided them.

Wednesdays in Mississippi brought black and white women from the North to visit with black and white women in the South. The teams of women traveled to Jackson, Mississippi on Tuesdays, traveled across the state on Wednesdays to work with freedom schools, and returned home on Thursdays. For pragmatic reasons of safety, the women worked in single-race groups, but always made sure to have one mixed-race group meeting during each trip. Wednesdays in Mississippi continued in the summer of 1965 with a slightly more professional focus on teachers and social workers, and in 1966 became "Workshops in Mississippi," a program to help black and white women and their families achieve better economic conditions. The National Council of Negro Women continues to work in Mississippi communities today.

Wednesdays in Mississippi was the only civil rights program led by a national women's organization (the National Council of Negro Women, in partnership with the National Council of Catholic Women, the National Council of Jewish Women, Church Women United, the Young Women's Christian Association, the League of Women Voters, and the American Association of University Women).

Introduction: Different Points of View

- If you have already taught Lesson 4:

- Remind your students that in 1964, approximately 1000 young Northerners, many of them Jews, went south as part of Freedom Summer, a community organizing project.

- Ask your students: What did these young people hope to accomplish and what kinds of projects did they take part in?

(Possible responses might include: Freedom Schools, registering voters, organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, seeing for themselves what was really happening in the South, providing support to southern African Americans, etc.)

- OR if you haven't taught Lesson 4, you may want to review the essay for Unit 2 lessons 4 and 5, and/or review Unit 2 lesson 4, and share some of the highlights with your students at this time.

- Distribute copies of "Letter from a Parent" Document Study to your students (either the transcript or copies of the original letter). Explain that this is a letter between a young woman who was part of Freedom Summer and her father. You may want to provide some biographical background on Vivian Rothstein (found at the top of the letter). Have one of your students read the letter out loud. Stop him/her as necessary to explain terms or phrases with which your students might not be familiar.

- Discuss the questions from the "Letter from a Parent" Document Study.

- Explain that there was some conflict between generations about civil rights activism. Sometimes parents didn't understand their children's ideals. Other times, parents shared the same ideals (often having taught their children their own values), but feared for their children's safety. Some of those in the latter category also chose to get involved in the Civil Rights Movement and organized their own community projects. You may want to read the "Statement by Carolyn Goodman, June 1965" to illustrate the perspective of one parent whose son was murdered because of his civil rights activism but who continued to stand behind his decision to go south.

Different Organizational Models - Part A

- Distribute copies of the Community Organizing Chart to your class. Together, fill out the information about Freedom Summer in the middle column of the chart, using what your students learned in the Community Organizing I: Freedom Summer lesson (or filling it in as you again go over the basics of that lesson).

- Explain that Freedom Summer represents one type of community organizing project and a model that was popular during the Civil Rights Movement; however, it wasn't the only model. Another (lesser-known) project and model was Wednesdays in Mississippi, also known as WIMS. The project was founded by an African American woman, Dorothy Height, and a white Jewish woman, Polly Cowan. They organized teams of black and white women from the North to meet with and support teams of black and white women in the South. Their trips centered on spending Wednesdays in Mississippi working for civil rights and the education of the black community. Run by the National Council for Negro Women, WIMS also drew participants from faith-based groups such as the National Council of Catholic Women, the National Council of Jewish Women, and Church Women United. Approximately 25% of the white women who participated in WIMS were Jewish. (See the WIMS essay for further details.)

Film clips from Wednesdays in Mississippi documentary

- Watch the three short clips of footage from the Wednesdays in Mississippi documentary film project. After each clip, ask students to turn to the person next to them and discuss one or two of the questions on their discussion sheet. Depending on how much time you have and how comfortable your students are with verbal discussion vs. writing, consider having your students fill in information on their chart after each of the film clips rather than waiting until the end.

- "Portraits from Wednesdays in Mississippi" (3:42):

The first clip looks at the different experiences of the Northern and Southern Wednesdays women through interviews with Beatrice "Buddy" Mayer (part of the Chicago team) and Elaine Crystal, who as a member of the Jackson, Mississippi team hosted Mayer when she came down. - "A Journey South" (2:58):

The second clip describes the danger the Wednesdays women encountered and reveals the dormant racism that existed in even some of the Wednesdays women. Susan Stedman and Doris V. Wilson of the Jackson team describe meeting the Northern women at the airport, with Klu Klux Klan members watching and spitting on the women as they arrived. Edith Savage Jennings, the first black woman to meet with a group of white women in Jackson, tells of how after she (intentionally) removed her glove none of the women were willing to shake her hand. - "WIMS: A Model of Women's Activism and Social Change" (2:20):

The third clip addresses the significance of organizing women in particular, and the impact of relatively well-off white and black women from the North and South working together for social change. Includes observations by historians Debra Schultz and Deborah Gray White, as well as by Polly Cowan's daughter, Holly Shulman, and her daughter-in-law, Rabbi Rachel Cowan.

- "Portraits from Wednesdays in Mississippi" (3:42):

- Bring the group back together. Ask a few pairs to share a couple examples of what they discussed, perhaps focusing on points of disagreement between them, or on things they found particularly surprising or confusing.

Different Organizational Models - Part B

- Ask students to turn back to their copies of the Community Organizing Chart and fill in information about Wednesdays in Mississippi in the right-hand column. Let students know they will have a chance to add more to that column in a little while.

- Distribute copies of Wednesdays in Mississippi Documents. Begin by looking at "Wednesdays in Mississippi" – Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator, 1964. Ask students to take turns reading it aloud, or break into small groups. Encourage students to draw connections between the film clips and this document, and discuss any surprises or disparities they notice.

- Have three students each read one of the remaining documents out loud. These documents are excerpts from oral history interviews conducted with WIMS participants, in which the women reflect back on their experiences. (If you have students with acting experience or strong voices, invite each of the three readers to come up to the front of the class when it is his/her turn.)

- Once again encourage students to draw connections between the film clips and these oral history excerpts, and discuss any surprises or disparities they notice.

- Using what they learned from the documents studied, have students finish filling in the Wednesdays in Mississippi section of their charts.

- When all of your students have finished their chart, discuss the following questions:

- Different organizations were involved in these two projects. How were these organizations similar and/or different? How do you think these differences and/or similarities affected the work they were doing?

- How did the goals and motivations of the participants in the two different projects overlap? What were some differences in the goals and motivations? What role do you think the age of the participants played in their goals and motivations? [Note in particular what Dorothy Height recalls in her interview: that Polly Cowan was motivated to start WIMS because of the ways the Freedom Summer volunteers – including her own children – were being described.] What role do you think gender played in their goals and motivations?

- Think back to the letter between Vivian and her father that we read at the beginning of class. How do you think each would have felt about the work being done by Wednesdays in Mississippi?

- What do you think is the significance these two different models had in terms of the Civil Rights Movement as a whole?

- How does knowing about WIMS impact your image of the Civil Rights Movement, and how Jews were involved?

OPTIONAL

For an additional assignment or class activity, interview a woman activist. This can be done in class, by bringing in a speaker and interviewing her in front of the class, or as an outside assignment, in which students choose someone to interview themselves. See JWA's "How-To" section for a downloadable oral history guide and a set of "Twenty Questions" for interviewing American Jewish women. Be sure to ask questions about the role of gender and the role of community in her activism.

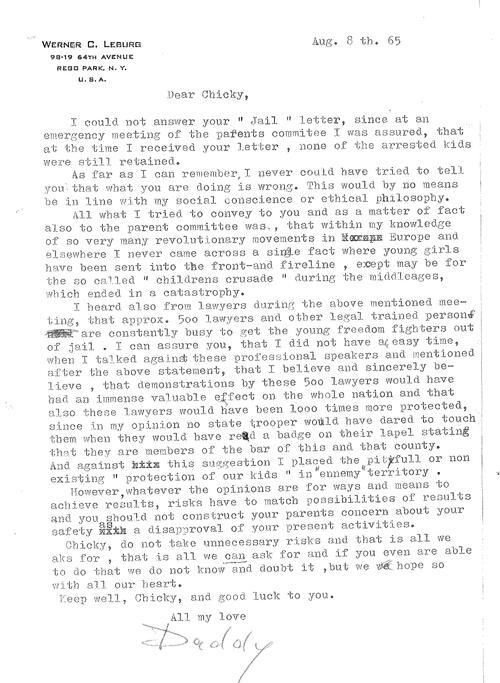

Letter from a Parent

Context

Vivian Rothstein (called "Chicky" in this letter from her father) was born in New York to German Jewish parents who fled Nazi Germany. She was raised in Los Angeles and attended UC Berkeley where she became involved in civil rights campaigns in the Bay Area. She was recruited to the Mississippi Freedom Summer program in 1964 and, after 10 days in jail with several hundred others for parading without a permit in Jackson, Mississippi, was assigned to work with the Freedom Democratic Party in Leake County. The Civil Rights Movement set her on a course of community organizing which led to involvement in the anti-war, women's liberation, and economic justice movements. Today Rothstein works with the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy in efforts to end low wage poverty in Southern California.

Letter to Vivian "Chicky" Leburg from Werner Leburg, August 8, 1965

Werner Leburg to Vivan "Chicky" Leburg, August 8, 1965.

Courtesy of Vivian Rothstein.

Discussion Questions

- What is the father's concern about what Vivian has chosen to do? Knowing what you know about Freedom Summer, do you think her father is justified? Why or why not?

- How do you think Vivian understands her father's concern? What is your evidence?

- How do you think Vivian's father really feels about her choice? What is your evidence?

- If you were a parent of a child going to Mississippi during the summer of 1964, how do you think you would have felt? What actions might you have taken as a result of your feelings?

Statement by Carolyn Goodman

Context

Carolyn Goodman was a psychologist and life-long activist. She and her husband, Robert Goodman, raised their three sons to be engaged in the world. In 1964, their son Andrew went to Mississippi as a volunteer with the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project and became one of the three civil rights workers who were disappeared and murdered by the Klan in Neshoba County. For the rest of her life, until her death in 2007 at age 91, Carolyn Goodman carried forward Andy’s legacy through her own activism, protesting civil rights abuses and getting arrested into her 80s, and traveling down to Mississippi to testify at the 2005 trial of a Klan leader who was finally indicted and found guilty of manslaughter in the deaths of the three civil rights workers.

Statement by Carolyn Goodman, June 1965

Wednesdays in Mississippi: A Documentary Film

Note

These film clips were prepared for the Jewish Women’s Archive by Marlene McCurtis, Cathee Weiss, and Joy Silverman, producers of a full-length documentary on Wednesdays in Mississippi. (See wimsfilmproject.com).

Portraits from Wednesdays in Mississippi, 2010

Activists speak about community response to integration in the mid 1960s. Portraits from Wednesdays in Mississippi. Flash video, 4 mins., Los Angeles: Wednesdays in Mississippi Documentary Film Project, 2010. This film clip was prepared for the Jewish Women's Archive by Marlene McCurtis, Cathee Weiss, and Joy Silverman, producers of a full-length documentary on Wednesdays in Mississippi. (See http://wimsfilmproject.com)

A Journey South

A Journey South. Flash video, 3 mins., Los Angeles: Wednesdays in Mississippi Documentary Film Project, 2010.

This film clip was prepared for the Jewish Women's Archive by Marlene McCurtis, Cathee Weiss, and Joy Silverman, producers of a full-length documentary on Wednesdays in Mississippi. (See http://wimsfilmproject.com)

"WIMS: A Model of Women’s Activism and Social Change," 2010

WIMS: A Model of Women’s Activism and Social Change. Flash video, 4 mins., Los Angeles: Wednesdays in Mississippi Documentary Film Project, 2010.

This film clip was prepared for the Jewish Women's Archive by Marlene McCurtis, Cathee Weiss, and Joy Silverman, producers of a full-length documentary on Wednesdays in Mississippi. (See http://wimsfilmproject.com)

Courtesy of Wednesdays in Mississippi Documentary Film Project.

Discussion Questions

"Portraits from Wednesdays in Mississippi"

- What stood out to you the most, from what you heard and saw in the film clip?

- What do you think motivated each of these women to take part in WIMS? What, if any, role does being Jewish seem to play in their work?

- How do you think Buddy Mayer and Elaine Crystal represent and defy stereotypes of Northerners and Southerners during the 1960s?

"A Journey South"

- The women shared different perspectives on the danger present. Based on the film clip, how do you think the inherent danger affected their work and their relationships with each other?

- How might you reconcile the civil rights activism of the Southern white Wednesdays women and their fear of/refusal to shake the hand of a black Northern activist?

"WIMS: A Model of Activism and Social Change"

- The WIMS activists worked together across racial, geographic, and class lines, but specifically limited their membership to women. What do the speakers in the film clips see as the significance of women working together?

- Do you find this aspect of their work significant? Why or Why not?

- Rabbi Rachel Cowan says that at the time, she and other activists in SNCC thought that they were more revolutionary than the WIMS women, but that looking back, she sees the WIMS women as just as dangerous, if not more so. How would you evaluate WIMS? What, if anything, do you think was revolutionary and/or dangerous about these women?

- What aspects of the Wednesdays in Mississippi model for activism seem most relevant/applicable today? What aspects seem less relevant/applicable?

Wednesdays in Mississippi Documents

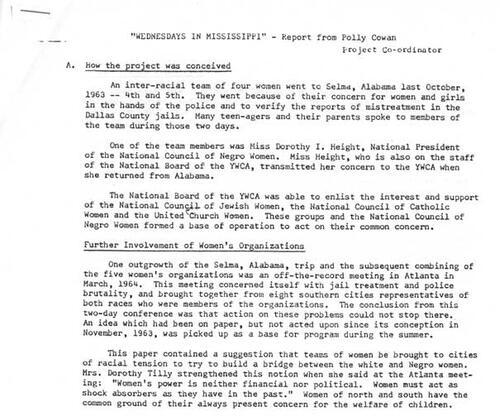

Wednesdays in Mississippi - Excerpts from the Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator, 1964

Wednesdays in Mississippi - Excerpts from the Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator, 1964

How the project was conceived

An inter-racial team of four women went to Selma, Alabama last October, 1963 – 4th and 5th. They went because of their concern for women and girls in the hands of the police and to verify the reports of mistreatment in the Dallas County jails. Many teen-agers and their parents spoke to members of the team during those two days.

One of the team members was Miss Dorothy I. Height, National President of the National Council of Negro Women. Miss Height, who is also on the staff of the National Board of the YWCA, transmitted her concern to the YWCA when she returned from Alabama.

The National Board of the YWCA was able to enlist the interest and support of the National Council of Jewish Women, the National Council of Catholic Women and the United Church Women. These groups and the National Council of Negro Women formed a base of operation to act on their common concern.

...

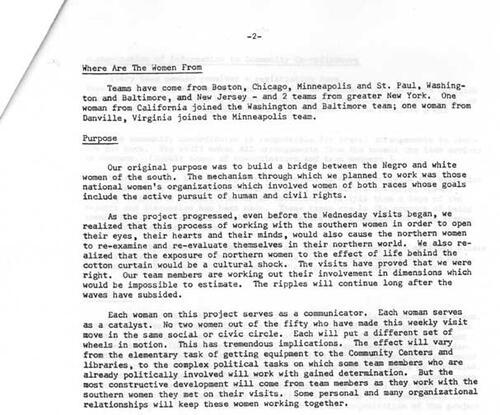

Purpose

Our original purpose was to build a bridge between the Negro and white women of the south. The mechanism through which we planned to work was those national women’s organizations which involved women of both races whose goals include the active pursuit of human and civil rights.

As the project progressed, even before the Wednesday visits began, we realized that this process of working with the southern women in order to open their eyes, their hearts and their minds, would also cause the northern women to re-examine and re-valuate themselves in their northern world. We also realized that the exposure of northern women to the effect of life behind the cotton curtain would be a cultural shock. The visits have proved that we were right. Our team members are working out their involvement in dimensions which would be impossible to estimate. The ripples will continue long after the waves have subsided.

Transcript of excerpts from Polly Cowan, "Wednesdays in Mississippi - Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator," 1964. Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work exhibit website.

Polly Cowan's Report on Wednesdays from Mississippi, 1964, page 1

"Wednesdays in Mississippi - Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator," 1964, page 1. Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work exhibit website. (See The Creation: Beginning: The Call for Action: The Start)

Courtesy of the National Park Service/Mary McLeod Bethune Council House.

Polly Cowan's Report on Wednesdays from Mississippi, 1964, page 2

"Wednesdays in Mississippi - Report from Polly Cowan, Project Coordinator," 1964, page 2. Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work exhibit website. (See The Creation: Goals: "Wednesdays in Mississippi" by Polly Cowan)

Courtesy of the National Park Service/Mary McLeod Bethune Council House.

Excerpts from Dorothy Height Oral History

Well, Polly [Cowan] knew of the work we were doing with some of the Head Start people down in Mississippi…She wrote a little note back to me, and she said – because by this time things were heating up in Mississippi. Bob Moses had decided that though he was a successful teacher, he would go down there and organize Freedom Schools. So she wrote and she said, ‘The word is out that all of those young people going from Ivy League colleges are communists.’* And she said, ‘My children are going, and I know there are other women who’d want to kind of be there to support their children and to let it be known that we are responsible people.’

She said, ‘I think if we could get the Cadillac crowd to do something I would call Wednesdays in Mississippi, that they would prepare and go in on Tuesday, that they would give some kind of a service.’ She said, ‘We don’t want them to go as sightseers. They have to be willing to do something that furthers the movement.’ And then we would somehow find a way to get together and then come out on Thursdays and go home, each one committed to doing something about civil rights back in their community, but also helping to expose the conditions that are affecting people in Mississippi…

Then we made a list of women that we thought of who would be very good. We began to think of women who had skills, who could do something. Augusta Baker, who was a librarian at the county library, we said, ‘She’s a good storyteller. We would have her.’ We thought of women like [Ellen] Terry, said if we had her, she’s a poet and she writes, and the like…

*In this context, “communist” was meant as a derogatory term. It was also sometimes used as a shorthand way to imply “Jewish” (due to the association of Jews and radicalism in the early 20th century).

Dorothy Height, interviewed by Holly Cowan Shulman for "Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work.” 16 October 2002. Permission to use granted by Holly C. Shulman.

Excerpt from Sylvia Weinberg Radov Oral History

The original purpose [of WIMS], as I understood it, was to give a sense of legitimacy to these college kids, to our kids, not mine, but it was a pretty close neighborhood. Those were our kids. And come down to Mississippi, a bunch of lovely ladies of all colors and ages, and to come dressed like ladies and behave like ladies, which we didn’t ordinarily—we spent a lot of time in blue jeans—and show the kids that we cared, and to live in the community and show the community that we were nice ladies with good backgrounds and good thoughts, a good education, and we were to scout out our own place to fit into this. It sounded like a great idea to me.…I felt it was the right thing to do. First of all, I did have a real connection and a real sympathy and interest in what the college kids were doing that year. I really did. And if this was some help to them—and it was presented originally more as a backup for the kids, and there’s no reason—for the same reason if one of the kids in the neighborhood fell off his bike in front of your house, you picked him up and brushed him off. That was the same thing. But of course, it developed to be much more…

Well, we met down at the airport, and we took a plane together, and Doris met us with a car and dropped us off where we were supposed to be. I don’t know, I was insecure. I could find my way around Paris and I could get along very fine in London, but I wasn’t real sure about what I could do in Jackson, Mississippi, and she was our shepherd…

I’m trying to think what else [we did]. Mostly we ate in each other’s homes. We didn’t go out for fancy meals at a restaurant, and we did not take on the right to sit at the same soda fountain kind of a thing. That’s not what we were after. That was an issue at the time, too… Polly’s eyes were way above a shared soda. Am I right? And her eyes were to support the kids and to help guarantee the right to vote and to live where you wanted to live. I think that’s about as much as we could handle. That’s a big bite at that time. It doesn’t sound like anything now.

Sylvia Weinberg Radov, interviewed by Amy Murrell, Chicago, Illinois, 25 June 2002. Permission to use granted by Holly C. Shulman.

Excerpt from Oral History with Beatrice "Buddy" Cummings Mayer

First of all, I thought that Wednesdays was a very brave, innovative moral thrust into the human neglect and abuse of civil rights violations. It was the most innovative and total participatory attack on civil rights abuses from a community approach that had so differed from the politician’s approach. This, I thought, was a people-to-people approach; and that, I thought, was how it was so different and so appropriate, so unique to work with the people most effective very much on a one-to-one basis as opposed through any of the existing political processes starting with the president down and going to all of the different national organizations that had some sort of a political base. This was not a political base. It was nonpartisan, and it was really, I think, from heart to heart and from mind to heart… I think the civil rights movement would have been incomplete if present and future generations only thought of it as a political process led by political leaders, and that individuals like myself didn’t have an opportunity to both express their concerns and to participate in trying to build bridges.”

Beatrice “Buddy” Mayer, interviewed by Holly Cowan Shulman, Chicago, Illinois, 25 June 2002. Permission to use granted by Holly C. Shulman.

Community Organizing Chart

| Mississippi Freedom Summer | Wednesdays in Mississippi | |

|---|---|---|

| What organizations were involved in the project? | ||

| What were the age, gender, and background of the participants? | ||

| What kinds of experience did the participants bring to the project? | ||

| How much time did they spend in Mississippi? | ||

| What were the goals/purpose of going to Mississippi? | ||

| What kinds of work did the participants do in Mississippi? |

Wednesdays in Mississippi (WIMS)

Wednesdays in Mississippi was founded by Polly Cowan (a Jewish woman) and Dorothy Height (an African American woman). They wanted to get teams of interracial, interfaith Northern women to learn about the situation in the South and to support their Southern counterparts. The model was for women to prepare on Tuesday, for the Northern women to go down to Mississippi and do service work on Wednesday (staying in the homes of their Southern counterparts) and return to the North on Thursday or Friday. Their work was often connected to Freedom Summer and Freedom Schools. While there, these women/community leaders would also keep any eye on the safety of women and youth doing Civil Rights work in Mississippi.

Community Organizing

An approach to social change that involves bringing community members together to form powerful organizations that allow them to act on their own behalf to make systemic changes in their lives. Community organizing aims to generate collective power for those who have been powerless and to create social change through collective action. The term and organizing model was originated by Saul Alinksy, a Jewish activist from Chicago and founder of the Industrial Areas Foundation.

Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work - exhibit website

Wednesdays in Mississippi: Civil Rights as Women's Work - exhibit website: www2.vcdh.virginia.edu/WIMS/

Jewish Women's Archive "We Remember" article on Polly Cowan

Jewish Women's Archive We Remember article on Polly Cowan: jwa.org/weremember/cowan-polly

Wednesdays in Mississippi from Lilith Magazine

Wednesdays in Mississippi: How Jewish Was My Mother's Civil Rights Activism? by Holly Cowan Shulman in Lilith Magazine.

There was a great story on NPR on June 5, 2013 about the 50th anniversary of Medgar Evers' death. You can find it here: http://www.npr.org/blogs/codeswitch/2013/06/05/188727790/fifty-years-after-medgar-evers-killing-the-scars-remain

For those interested, you can find an interview with the director of the WIMS documentary and participants on YouTube. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v...