Barbara Seaman

A pioneering health feminist, author, and central figure in the second wave of the women’s movement, Barbara Seaman was best known for her opposition to mass-prescribed hormones, including diethylstilbestrol, estrogen replacement therapy, and the high-dose birth control pill. Her first book, The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill (1969), provoked Senate hearings on pill safety. Her efforts forced pharmaceutical companies to provide written disclosures of any possible side effects in each pill packet, the first mandate of its kind. Seaman was an architect of the “feminist health movement,” which advocated informed consent and patient rights at a time when men (doctors, husbands, legislators, and religious leaders) made decisions about women’s bodies.

A pioneering health feminist, author, and central figure in the second wave of the women’s movement, Barbara Seaman was best known for her opposition to mass-prescribed hormones, including diethylstilbestrol, estrogen replacement therapy, and the high-dose birth control pill. Her first book, The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill (1969), provoked Senate hearings on pill safety. Her efforts forced pharmaceutical companies to provide written disclosures of any possible side effects in each pill packet, the first mandate of its kind. Seaman was an architect of the “feminist health movement,” which advocated informed consent and patient rights at a time when men (doctors, husbands, legislators, and religious leaders) generally made decisions about women’s bodies.

Early Life & Education

Barbara Ann Rosner was born on September 11, 1935, to Henry J. and Sophie (Kimels) Rosner, who had met at a picnic of the Young People’s Socialist League. Henry Rosner was a researcher for Norman Thomas (candidate for president on the Socialist ticket) and later assistant commissioner of welfare programs for New York City. Sophie had a variety of careers, including teaching English at James Madison High, a public school in Brooklyn.

Seaman’s early childhood was characterized by abandonment, a consequence of her parents’ marital strife. At age three, for example, she was sent to a two-month sleepaway camp, at the end of which no one came to pick her up. Her parents briefly divorced in the 1940s, resulting in Barbara and her sister Jeri (b. 1943) being placed in foster care in Woodstock, New York. Her parents subsequently remarried, had a third child, Elaine (b. 1949), and remained together until Sophie Rosner’s death in 1970.

As a teenager, Seaman was extroverted, glamorous, and compulsively social. She showed early talent for writing and, according to her family, longed to be a songwriter. She fought violently with her temperamental, competitive mother. Seaman later told friends that her mother often damned her with faint praise, telling her she was “smart, but not like Kiki Bader”—a student at James Madison High more commonly known as Ruth.

Seaman won a scholarship to attend Ohio’s Oberlin College in 1952. At nineteen, during a summer internship in Washington, D.C., she impetuously married Peter Marx (the brother-in-law of filmmaker Melvin Van Peebles). Seaman returned to college saddled with Marx, and the marriage was quickly annulled. She graduated in 1956 with a degree in History. The next year, she married Gideon Seaman, a psychiatry resident and the son of the suffragist Sylvia Seaman.

Career Beginnings

A trauma after the birth of her son Noah (b. 1957) may have triggered Barbara Seaman’s life-long campaign to empower women to speak up to male doctors. Still in the hospital post-delivery, her doctor administered a strong laxative to her despite the fact that she had informed him she was breastfeeding. The drug passed through her milk to Noah, who became seriously ill. Three years later, when her second child, Elana, was born, Seaman vowed to follow her own instincts. She “palmed” the medications and threw them away when the nurse wasn’t looking. “The strategy worked, my baby and I did beautifully,” Seaman recounted in the 25th-anniversary edition of The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill. She wrote up the experience and sold her first magazine piece, for which she was paid $50. As became customary for her throughout the 1960s, the reader response to her revolt was outsized, a clue that women were hungry for real medical information in order to form their own decisions.

By 1965, Seaman lived on the upper west side of Manhattan with her three young children (Shira was born in 1962), working on a typewriter in the bedroom while Gideon saw patients in a cordoned-off suite within their twelve-room apartment. She had health columns in Ladies’ Home Journal, McCall’s, and Family Circle, among other magazines, and a combined monthly readership of more than twelve million.

The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill

Barbara Seaman frequently joked that her married name was perfect for a journalist who wrote about birth control. In 1968, the women’s liberation movement was building momentum in New York City, approximately seven million women were taking the pill, and Seaman was earning a certificate in science writing from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. The pill, approved in 1960, was lauded as a win-win for women—freedom through a pharmaceutical, rigorously tested and extremely safe. Readers’ letters to Seaman told a different story: some women were having terrible side effects, and their doctors were dismissing their concerns.

At Columbia, Seaman pored over the medical literature and discovered that the pill was implicated in blood clots, strokes, cancers, depression, weight gain, and deaths. With dubious consent, the pill had been tested on “half of the women of Puerto Rico.” To the average consumer, that sounded like a large-scale study, but Seaman learned that just 200 women had taken it for more than a year. Of those, three had died, and seventeen percent experienced severe and intolerable side-effects such as nausea, dizziness, and vomiting. In 1969, Seaman published The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill, which exposed the risks of the birth control pill and how little doctors knew of its potentially lethal side effects, especially for the 35 percent of women who smoked.

Pharmaceutical companies attempted to discredit Seaman as hysterical and opposed to sexual freedom, but the book resonated with its intended audience of women on the pill, magnetizing their stories of ill effects. In 1970, Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson (the creator of Earth Day) held hearings on the pill’s safety. Nelson invited drug companies and the FDA to testify, but not patients. Furious that the people affected by this drug would not be heard, Seaman urged activists from D.C. Women’s Liberation (a local feminist group) to protest from the gallery. The repeated feminist disruptions landed the hearings on the nightly news. Seaman’s exposé led directly to patient warnings listing side effects on all pill packets.

Women’s Health Movement

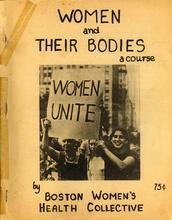

Despite the success of “Docs Case,” as Seaman nicknamed it, her magazine contracts were not renewed, perhaps because her approach was not advertiser friendly. As she became more involved with women’s liberation, Seaman wrote Free and Female: The Sex Life of Contemporary Women and began to coalesce disparate activist threads—the Boston Health Book Collective (later called Our Bodies, Ourselves), Byllye Avery’s Black Women’s Health Project, and Lorraine Rothman and Carol Downer’s development of menstrual extraction (DIY early abortion)—into a feminist women’s health movement.

In 1975, Seaman co-founded the National Women’s Health Network, a patient advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. In 1978, she published Women and the Crisis in Sex Hormones (putatively “co-authored” with her husband Gideon), which prompted a government task force on the effects of diethylstilbestrol, or DES, on women whose mothers had been prescribed it to prevent miscarriage. Many of these “DES daughters” were diagnosed with a rare vaginal cancer as young women and underwent hysterectomies. As a member of the task force and after, Seaman fought for their right to sue drug companies for their medical costs.

The Seamans separated in 1978 and later divorced; Barbara kept the on-brand surname. In 1982, she married her high school sweetheart, Milton Forman.

Lovely Me: The Life of Jacqueline Susann

After penning several successful non-fiction books about women’s, Seaman wanted to tackle a biography and began looking for a notable female figure without one. Initially, she researched the life of the British writer, spiritualist, and women’s rights advocate Annie Besant. In 1980, at a publishing lunch with her agent and an executive at William Morrow, talk turned to Valley of the Dolls author Jacqueline Susann. At first glance, a Pucci-wearing pulp writer who fed her poodle caviar seemed to be an odd subject for a serious health writer, but as the backlash against women’s liberation picked up steam, Seaman began to understand Susann’s triumph as proto-feminist. In her framing, a middling actress with a lot of chutzpah receives a diagnosis of breast cancer at age 42, makes a pact with God, and then wills one of the most successful publishing careers in history before her death twelve years later. All the while, no one knows she is sick. Seaman argued that Valley of the Dolls (published in 1966) was “an early storm signal to both the drug culture and the women’s movement.”

Lovely Me: The Life of Jacqueline Susann, published in 1987, elicited a wide range of positive reviews. In Mademoiselle, Joyce Maynard called Seaman “a marvelous storyteller who…research[ed] Susann’s life with no less rigor than she might have if her subject had been Eleanor Roosevelt or Marie Curie.” Indeed, Seaman interviewed many dozens of Susann’s friends and associates, including Alexander Korda, her editor after Valley of the Dolls. Korda later authored an eight-page article for The New Yorker about his brief relationship with Susann, which was optioned for film for $750,000. Seaman believed Lovely Me had to have been the primary source material for any movie about Susann’s life, but Korda insisted he hardly remembered their interview and implied he had not read her book. Lovely Me was optioned for $75,000 by Michele Lee, a star of Knots Landing, and turned into the TV biopic Scandalous Me in 1998.

Criticism

Seaman was referred to as the “Ralph Nader of the pill,” “a fairy godmother to those of us who were becoming women's health activists in the 1970s,” and “the first prophet of the women’s health movement,” but her critics included feminists and women’s health reporters who critiqued her hard line as too simplistic. In a New York Times review of The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women, Gina Kolata noted that Seaman “tends to hold estrogen critics to a looser standard than she does estrogen promoters.” Other reviews questioned her tendency to cast all drug companies as sacrificing health for profit and all doctors as dismissive of women or in the pocket of big pharma.

Later Life

Seaman always cut a unique figure in the New York city women’s movement—a mink-coat clad, much-married radical feminist. By the 1990s, Seaman was single for the first time in her adult life (she divorced husband Milton Forman in 1988 and alluded to domestic violence in their marriage). As relentless and eager to organize as ever, she carried pamphlets or a petition in her purse, ready to lobby anyone she encountered. She also mentored dozens of young feminists, generously offering her contacts, ideas, expertise, time—even her apartment—to anyone who asked. Her compulsive connecting was strategic as well as genuine; she was afraid of being abandoned by official histories of second-wave feminism. Her generosity wasn’t always warranted. According to L. Frank Baum biographer and dear friend Michael Patrick Ahearn, Seaman was a “great networker, but not always the best judge of character.”

Seaman was fiercely suspicious of drug companies, but not of another industry that misrepresented the lethality of its products: tobacco. At sixteen, her doctor suggested she smoke to help with weight loss and she quickly became addicted. She tried to quit multiple times but chain-smoked into her fifties, which annoyed and upset her children. Her daughter Elana recalled being sent to the corner store to pick up cartons of Carltons. Shira had serious asthma and allergies. Once, Seaman burned a hole in Elana’s fancy party dress as they exited a cab. When her children pointed out the incoherence of fighting for women’s health yet smoking three or four packs per day, Seaman responded: “Everyone has the right to choose their own form of suicide.”

Seaman was diagnosed with lung cancer in May of 2007. Apart from her family and a few friends, she kept her illness a secret. Her last months were spent primarily with her mentee and assistant Laura Eldridge, finishing two books and organizing her archive for the Schlesinger Library. Elana later remember that at a book party a few weeks before she died, her mother stayed for hours, laughing and talking, no one having a clue she was ill: “She was always the last person to leave a party. She couldn’t say goodbye.”

Barbara Seaman died on February 27, 2008. At her request, eulogists included Seaman’s stepmother Ruth Gruber, Erica Jong, Phyllis Chesler, and Laura Eldridge, along with dozens of other friends, family, and feminists. As fitting someone who couldn’t say goodbye, the funeral lasted nearly five hours.

Selected Works by Barbara Seaman

The Doctor’s Case Against the Pill. Nashville: Hunter House, 1995. First published 1969.

Women and the Crisis in Sex Hormones. New York: Bantam Books, 1978.

Free and Female: The Sex Life of Contemporary Women. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1972.

The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth. New York: Hyperion, 2003.

Lovely Me: The Life of Jacqueline Susann. New York: Morrow, 1987.

Baker, Christina Looper and Christina Baker Kline, eds. The Conversation Begins: Mothers and Daughters Talk About Living feminism. New York: Bantam, 1996.

Drucker, Jeri Rosner (Barbara Seaman’s younger sister), interviewed by Jennifer Baumgardner, March 27, 2020.

Hearn, Michael Patrick (Barbara Seaman’s close friend and confidante), interviewed by Jennifer Baumgardner, March 29, 2020.

Seaman, Barbara. Foreword to the 25th Anniversary edition of The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill. Nashville: Hunter House, 1995.

Seaman, Shira (Barbara Seaman’s youngest child), interviewed by Jennifer Baumgardner, March 27, 2020.

“A Tribute to Barbara Seaman: Triggering a Revolution in Women’s Health Care.” On the Issues, Spring 2011.