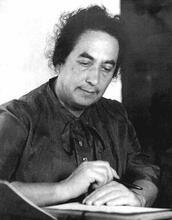

Antonietta Raphaël

Antonietta Raphaël was a painter and sculptor who rose to fame in the 1950s. Raphaël settled in Rome in 1919 and attended the Academy of Fine Arts. There she met Roman painter Mario Mafai, whom she later married. Imbued with memories of Jewish rites, Raphaël’s painting was expressionistic in style and rich in Fauvist coloring. Raphaël’s paintings were seen for the first time in Rome in 1929 at the First Exhibition of the Fascist Syndicates, where her Landscape was shown alongside two paintings by Mafai. During the war, the couple escaped to Genoa, and Raphaël took up sculpting. In the 1950s, Raphaël exhibited her works worldwide. After her husband died, she felt increasingly impelled to paint, and her later works were displayed at many exhibitions.

Early Life and Family

Antonietta Raphaël was born in Kaunas (Lithuania) in 1895, despite her declaring herself to be five years younger. The youngest child of Rabbi Simon Raphaël, coming after thirteen sons, lost her father during the winter of 1903. “My father died when I was seven or eight years old,” she wrote in her diary on July 20, 1968. “I remained with my mother with no means to survive.” Her thirteen brothers were all tailors and had moved to London before Antonietta. Presumably, in 1905, she moved to London with her mother Katia (née Horowitz). She studied music and made a living by embroidering. After attaining a diploma in piano, she mostly taught music and became a frequent visitor to the British Museum, where she was particularly fascinated by Egyptian sculptures. In London, she soon met the sculptor Jacob Epstein (1880–1959), but she herself started drawing only in 1918. In fact, she was totally devoted to music and, having a good voice, to singing.

After her mother’s death in 1919, she spent a winter in Paris and then settled in Rome where she attended the Academy of Fine Arts and in particular the life class. There she met a Roman painter, Mario Mafai (1902–1965), younger than herself, with whom she started a lifelong relationship. Only much later, on July 20, 1935, would they get married. Early in 1926 she gave birth to their first daughter, Myriam (who became a renowned journalist), and in 1928 to Simona.

Early Painting Career

At that time Mafai shared his studio in via Cavour with another painter, Gino Bonichi, known as Scipione (1904–1933). Raphaël, Mafai, and Scipione soon joined into an artistic companionship, which became so well established that art critic Roberto Longhi (1890–1970) named it the “School of via Cavour.” Their style was characterized by a special visionarism, the use of a bright palette, and the warm tonalism that later characterized the so-called “Roman School.” It exerted an influence on some of the most important Italian painters of the twentieth century, such as the Jewish painter Corrado Cagli (1910–1976) and Giuseppe Capogrossi (1900–1972). Imbued with memories of Jewish rites, Raphaël’s painting was expressionistic in style and rich in Fauvist coloring. Of the three artists, she was the most inclined to a burning imagination, so much so that she has often and incorrectly been perceived as the very inspirer of the “School of via Cavour,” as “Chagall’s little foster sister,” as Longhi called her.

Artists of the time mostly employed the “Novecento” style, a revisitation of fifteenth- and sixteenth- century art displayed at several exhibitions in Italy and abroad, which was favored by the art critic Margherita Sarfatti and strongly supported by Mussolini. Raphaël, Mafai, and Scipione were clearly inspired by totally different ideas.

Raphaël’s paintings were seen for the first time in Rome in 1929 at the First Exhibition of the Fascist Syndicates, where her Landscape was shown alongside two paintings by Mafai, Sunset and Sunset on the Lungotevere. In the catalog, her name was Italianized and changed to “Raffael.”

France, Rome, and Sculpting

In February 1930, after the birth of their third daughter, Giulia, Raphaël and Mafai left for Paris. She stayed for four years, with short visits to Rome and London, where Epstein unsuccessfully tried to exhibit her work at the Redfern Gallery. In Paris, Raphaël met Chagall, who thought her art was still unripe and advised her not to exhibit there for the moment. In the French capital, the couple lived in poverty. She tried to earn by again giving piano lessons, taught English, and sold her embroideries. Very often there was almost nothing to eat, as Raphaël would later recall. “Just a piece of bread and a half egg were in the dish: I would push it toward Mario and he would it push it back toward me.” After Mafai’s return to Rome, Raphaël started studying sculpture, as a way to avoid domestic conflicts. “It is difficult for two painters to live together. I criticized him and he did the same with me. That’s why I attended an evening school of sculpture up to 1933, when I went back to Rome.” From that moment on Raphaël devoted herself mainly to sculpture. Although she loved stone, she made terracottas, cements, and bronzes. Her preferred subject were her daughters (Sleeping Myriam, 1933; Simona and her brush, 1935; Giulia’s Portrait and The three sisters, 1936; Simona’s Portrait and Giulia’s Head, 1938), though dramatic works are not missing (Escape from Sodoma, 1935–1936; Niobe, 1938). Her sculptures are characterized by full, rounded shapes, possibly echoing the French sculptor Aristide Maillol (1861–1944), to whose work she turned with a sensitivity far from academicism. There is also a perceptible indebtedness to Epstein.

To avoid Raphaël’s exile after the Fascist anti-Jewish laws were passed in November 1938, the entire family left Rome in July 1939 and took refuge in Genoa, at the home of the Jewish art collector Emilio Jesi and Alberto Della Ragione (1892–1976), who allowed Raphaël and her daughters to live safely till the end of World War II. (Mario was enlisted in the army in 1942.) Antonietta’s portraits of Emilio Jesi and Lucia Rodocanachi (Della Ragione’s mother) belong to this sad period as does a new version of her Tyrannicide.

Post-War Artistic Career

After the war Raphaël took part in important exhibitions, such as the 1948 National Survey of Figurative Arts held at the Rome National Gallery of Modern Art, where she showed Selfportrait and Genesis under the name “De Simon Raphaël,” thus adding her father’s given name to that of her family. She was also invited to the XXIV Biennale in Venice, where she exhibited The three sisters—a chalk of 1947. In 1950 she was again at the Biennale with three chalks (Escape from Sodoma, 1939; Figure of a woman, 1943; Dying bull, 1945). The following year she showed two terracottas (Portrait of Dr. Jesi and The little girl singing) and two bronzes (Portrait of painter Mafai and Portrait of painter Guttuso) at the VI Quadriennial Exhibition, where she was awarded one of the prizes for sculpture. In addition to exhibiting at the Biennales of 1952 and 1954, Raphaël participated in several competitions for monuments. In 1956 she toured China and exhibited in Peking with a number of Italian artists. Invited to the VIII Quadriennial (1959), she exhibited twelve works (paintings and sculptures) under the name Raphaël, adding “De Simon” in parentheses. After her husband’s death in 1965, she felt increasingly impelled to paint. Now at last under the name “Antonietta Raphaël,” her works were displayed at many exhibitions, amongst which Modern Art in Italy 1915–1935 is noteworthy. Curated by art critic and historian Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti (1910–1987), the exhibition was held in 1967 at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. It was followed by Contemporary Italian Sculptors, a traveling exhibition curated by the Quadriennial which opened at the Musée d’art moderne de la ville de Paris in November 1968 and toured Cairo, Teheran, Lisbon, Cologne, Budapest, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, and Hakone, Japan with its last stop in Malta in 1977.

During her last five years, Raphaël painted a number of large works. In 1975 she was hospitalized in a Roman hospital and died three days later in her sleep.

Alfredo Mezio, Raphael (sic), Ivrea 1960.

Marzio Pinottini, Scultura di Raphaël, exhibition catalogue, Milano 1971.

Sandra Orienti, Raphaël a Celano, exh. cat., Milano 1981.

Mario Mafai, Diario 1926-1965, Roma 1984.

Marzio Pinottini, Mafai e Raphaël. Una vita per l’arte, exhib. cat., Torino 1985.

Fortunato Bellonzi, La “Scuola Romana”, in G. Di Genova (ed), 3^ Biennale Nazionale d’Arte Contemporanea. GENERAZIONE PRIMO DECENNIO, Rieti/Bologna 1985.

Fabrizio D’Amico, Antonietta Raphaël, sculture, exh. cat., Milano/Roma 1985.

Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, I Mafai. Vite parallele, exh. cat., Roma 1994.

G. Di Genova, Storia dell’arte italiana del ’900: Generazione primo decennio, Bologna 1996.

Achille Bonito Oliva-Valerio Rivosecchi, Antonietta Raphaël. Materia e colore del sogno (with some pages from Raphaël’s diary), exh. cat., Roma 2000.