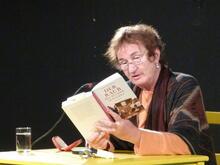

Ruth Peggy Sophie Parnass

Born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1927, Peggy Parnass grew up in Sweden, where she remained throughout World War II. Parnass’s experience reporting in the Berlin law courts from 1970 to 1978 formed the basis for her book Prozesse (Trials, 1978/1990). Her second book, Kleine radikale Minderheit (Small Radical Minority, 1985) shares the echoes of Prozesse by questioning how minorities interact within the multiple identities of the majority. Parnass continued to confront the meaning of being Jewish in Germany in a post-Holocaust society throughout her literary career. In 1982 Parnass and her colleague Axel Engsfeldt won the Bundesfilm Award for their film Von Richtern und anderen Sympathisanten (On Judges and Other Sympathizers) and in 1998 the City of Hamburg awarded her its Biermann-Rathjen Medal.

Personal Life and World War II

How many identities can a woman have? Peggy Parnass is a Jew, a woman, a German born in Hamburg and raised in Sweden, an author, a journalist, an actress, and, last but not least, a feminist. Born in Hamburg on October 11, 1927, Parnass is a person of great passion—in body, mind, heart, and soul. This passion directs her way of thinking and writing, particularly in the genres she prefers: reportage, political interviews, and political statements. The tone of her writing, which is always subjective, provocative, and fresh, is especially challenging on political and feminist matters. Indeed she abjures the separation of private and public lives that Hannah Arendt so adamantly advocated throughout her life. For example, she revealed details of her childhood in an interview with Erika Runge for the radio station Hessischer Rundfunk (1981), in which she spoke of the love affair between her mother, Herta Emanuel (Hamburg 1906–Treblinka 1942), who was half-Portuguese, and Simon (Tarnopol 1878–Treblinka 1942), known as Pudl, a Polish Jew, who was Peggy’s father. Pudl was a short man with black curly hair and an elegant moustache—“not like Hitler.” When the SS came for him, they took little Peggy away and afterwards gave her money for the tram, telling her to “Go to the Jewish orphanage.” In the interview published in her first book, Unter der Haut (Under the Skin, 1983), Parnass relates the story of her childhood—a childhood characterized by poverty under Nazi rule in Hamburg and exile in Sweden: “The Nazis were all around us. I don‘t know how Kissinger and others could ignore this.” Parnass avers that she was never really a child.

In Unter der Haut Parnass claims that memories are like a palimpsest. All her memories are connected to her mother and arise with a sensual perception of her mother’s body and outer appearance, which surrounds her with a unique aura. “She was small. With curly black hair. Much plaited hair in order to look more grown-up and tidy. Big grey eyes. Big nose. And a lot of mouth. She had a very fragrant skin, because of washing herself all the time in the kitchen.” Although her mother’s hands were roughened by hard work, in Parnass’s memories they seem to be lilies—a flower that serves as a metaphor for chasteness and purity. Not knowing what childhood really is, Parnass transfigures it into an idyll: a place, a “house” where she felt sheltered and where she could stay. In reality, her very unconventional, tough mother took her children—Peggy and her brother Gady—to the railway station in order to send them to Sweden. She herself, together with Pudl, was deported to the Warsaw Ghetto from where they were both transported to Treblinka and murdered in 1942. Gady later lived in Israel on A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Ein ha-Horesh. Parnass attended schools in Stockholm and London and universities in Hamburg and Paris, studying Russian, law, psychology, and especially Gestalt therapy. In 1949 she gave birth to a son, Kim Parnass.

Post-War Journalism

Parnass was a reporter in the Berlin law courts between 1970 and 1978. These reports form the basis for her book Prozesse (Trials, 1978/1990), which critics praised as a classic of journalism. Der Spiegel called her the queen of female journalists, one who works in a courtroom without distancing herself or claiming to be objective. Die Zeit saw her as glamorous and called her the most erotic person on the political left. “Peggy Parnass has the grace of ingenious women, such as those Germany knew in former times.” Parnass reported political cases, violent crime, and sexual offenses, but also less sensational cases; for example, she interviewed Wolf Biermann and Günther Wallraff in the Wallraff Trial. She participated in demonstrations such as the forbidden demonstration in Brokdorf (1978). But mainly she attended the trials of Nazi criminals accused of killing Jews.

Literary Works and Awards

In 1979 Parnass received the Joseph Drexel Prize for “outstanding achievements in journalism” and in 1980 the Fritz Bauer Award of the Humanist Union. Her book Prozesse presents the profoundly radical idiom of her language and style, which also typified her next book, Kleine radikale Minderheit (Small Radical Minority, 1985). The topic of the small radical minority interacts with the opening question of multiple identities. Parnass portrays a chain of small radical minorities, who embrace political themes such as squatters in Hamburg or questions of Jewish identity. Here one can also find Parnass’s confrontation with being Jewish in Germany today, as in her article Jüdin in Deutschland (A Jewish Woman in Germany). Unlike Barbara Honigmann in her novel Sohara’s Reise (1969), Parnass does not write along traditional lines. The topos of a specific “female-Jewish” collective art has no place in her writing. In this article, Parnass concedes that she cannot talk about her Jewish identity, not for reasons of privacy, but because it completely controls her life. She tried to talk about it in 1965 and again in 1980 for the book Fremd im eigenen Land (Strangers in One’s Own Country), edited by Henryk M. Broder, one of the most popular authors of Jewish literature of the post-Holocaust generation. Parnass confesses that as time passes she is less and less able to talk about her “second skin.” One of the reasons for her increasing silence on this score may be her left-wing political activity. Like some of her friends, she sees herself as falling between two poles: She does not feel accepted as a Jewe and confesses that Judaism plays a role in her life only because of Jew-baiting. In one of her childhood dreams she wants to become Chaplina, the female counterpart of Charlie Chaplin, a man she admired. Nevertheless, when Parnass talks about famous Jewish personages such as Franz Kafka or Rosa Luxemburg, it sounds like name dropping without deeper communicative connections.

In 1982 Parnass, together with her colleague Axel Engsfeldt, won the Bundesfilm Award for their film Von Richtern und anderen Sympathisanten (On Judges and Other Sympathizers) and in 1998 the City of Hamburg awarded her its Biermann-Rathjen Medal. Parnass’s vigilance, curiosity and passion for life are mirrored in all her books, which are a collection of wide-ranging articles and speeches, most of them first published in the magazine Konkret or in anthologies. Titles such as Süchtig nach Leben (Addicted to Life, 1990) reflect her attitude towards life as a challenge. Autobiographical stories alternate with political statements on issues such as Israel. As a feminist she is concerned with questions such as abortion and that of her Jewish identity in her book Mut und Leidenschaft (Courage and Passion, 1993/1997). The feminist issue appears again and again in interviews and dialogues between two women, as in the book on cartoonist Marie Marcks, which contains the latter’s political cartoons (1981). Creating art and earning money as a single woman is one of the points of discussion. The kibbutz as a lifestyle for women with children is another theme.

The short story “Gelüste” (Desires), from her book Süchtig nach Leben, tells of her late-discovered love of eating as a real pleasure. In another story in this book, “Trennungen” (Separations), Parnass reflects on different forms of separation from family members, for instance from her father Pudl, from her son, who left her when he was young, and from her mother. She confesses to failure in love affairs: love becomes a battlefield, its topography a chain of many separations.

Selected Works by Peggy Parnass

Monographs

Unter die Haut. Hamburg: 1983.

Kleine radikale Minderheit. Hamburg: 1985.

Prozesse. Berlin: 1978; (Erweiterte Neuausgabe Hamburg: 1990, Reinbek bei Hamburg: 1992).

Süchtig nach Leben. Hamburg: 1990.

Mut und Leidenschaft. Hamburg: 1993.

Marcks, Marie. Schöne Aussichten. Karrikaturen. Mit einem Interview von Peggy Parnass. Berlin: 1981 (Reihe politische Karrikatur).

Essays, Feuilletons, Criticism

“Warum XY-Zimmermann nicht nach Nazis fahndet. »Fahndung«—eine Kolumne von Peggy Parnass.” In Unsere Zeit [Essen], 25.4.1984, Nr. 80.

“Kindheit.” In Hans-Georg Behr: Winifred und Wolf. Eine historische Posse mit Gesang. (Für eine Schauspielerin und zwei Schauspieler [von denen einer auch Klavierspielen kann] mit einem Essay von Karl Markus Michel.) Berlin: 1998, 29–30.

Giordano, Ralph. “Ein Leben als Kunstwerk.” Ralph Giordano über Peggy Parnass. “Süchtig nach Leben.” Der Spiegel 22 (May 28, 1990): 208.

Henry, Ruth. “Gegen die Zeit. Aufsätze einer kritischen Beobachterin. Peggy Parnass: Unter die Haut.” Die Zeit, October 14, 1983.

Müller, Jutta. “Mit Herz und Verstand. Peggy Parnass’ “Süchtig nach Leben.” Frankfurter Rundschau, April 27, 1991.

Pagener, Gabriela. “Veränderungen von Denk- und Sehgewohnheiten. Zum neuen Buch von Peggy Parnass.” In Jüdische Allgemeine Wochenzeitung 38/41 (October 14, 1983).

Pagener-Neu, Gabriela. “‘Bild mir nicht ein, objektiv sein zu können.’ Peggy Parnass und die radikale Minderheit.” Jüdische Allgemeine Wochenzeitung 41/3 (January 17, 1986).

Troller, Georg Stefan. “Peggy Parnass: Kleine radikale Minderheit.” Die Zeit 50 (December 5, 1986).

Weigel, Sigrid. “Jüdische Kultur und Weiblichkeitin der Moderne. Zur Einführung.” In Jüdische Kultur und Weiblichkeitin der Moderne, edited by Inge Stephan, Sabine Schilling and Sigrid Weigel, 1–8. Köln: 1994.