Lilith

"Lady Lilith" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1866. Via Wikipedia.

Lilith’s character has evolved throughout the years. She began as a female demon common to many Middle Eastern cultures, appearing in the book of Isaiah, Babylonian Talmud, and incantation bowls from ancient Iraq and Iran. She is described as threatening the sexual and reproductive aspects of life, especially childbirth. A medieval Jewish text called the Alphabet of Ben Sira describes her as Adam’s first wife who disobeyed him and God and asserted her equality to Adam, giving a legendary origin to her demonic behavior. She also appears in Kabbalah as an evil reflection of the feminine aspect of God along with Samael. Jewish feminists, seizing upon her assertion of equality, have reclaimed Lilith as a symbol of autonomy, independence, and sexual liberation.

Until the late twentieth century the demon Lilith, Adam’s first wife, had a fearsome reputation as a kidnapper and murderer of children and seducer of men. Only with the advent of the feminist movement in the 1960s did she acquire her present high status as the model for independent women. The feminist theologian Judith Plaskow’s modern A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash on the story of Lilith played a key role in transforming Lilith from a demon to a role model.

The Lilith in Middle Eastern Literature

As an individual Lilith is first known from the Alphabet of Ben Sira, a provocative and often misogynist satirical Hebrew work of the eighth century CE, but the liliths as a category of demons, along with the male lilis, have existed for several thousand years.

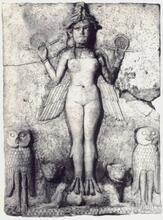

The Bible mentions the Lilith only once, as a dweller in waste places (Isaiah 34:14), but the characterization of the Lilith or the lili (in the singular or plural) as a seducer or slayer of children has a long pre-history in ancient Babylonian religion. J. A. Scurlock writes, “The lilû-demons and their female counterparts the lilitu or ardat lilî-demons were hungry for victims because they had once been human; they were the spirits of young men and women who had themselves died young.” These demons “slipped through windows into people’s houses looking for victims to take the place of husbands and wives whom they themselves never had.” Another, related demoness was Lamashtu, who threatened new-born babies and “had a disagreeable taste for human flesh and blood.” The figures of Lamashtu and the lilû and lilitu demons eventually converged to form one type of evil figure that seduced men and women and attacked children (Hutter).

The liliths are known particularly from the Aramaic incantation bowls from Sassanian and early Islamic Iraq and Iran (roughly 400–800 C.E.). These are ordinary earthenware bowls that ritual specialists or laypeople from the Jewish, Mandaean, Christian, and pagan communities, who lived in close proximity in the cities of Babylonia, inscribed with incantations in their own dialects of Aramaic. A drawing of a bound lilith or other demon often appears in the center of the bowl. The bowls’ purpose was usually to exorcise demons from the house or from the body of the clients named on the bowls, or to turn back malevolent magic that others had practiced against the clients.

The liliths appear in lists of evil spirits that often refer to the “male and female liliths,” reflecting the ancient conception that these evil demons could appear in either male or female form. The bowl-texts accuse the liliths of haunting people in dreams at night or visions of the day. One text describes the liliths “who appear to human beings, to men in the likeness of women and to women in the likeness of men, and they lie with all human beings at night and during the day” (Montgomery 117). Thus one prominent characteristic of the liliths is that they attack people in the sexual and reproductive realm of life. It is no wonder, therefore, that some of the writers of the bowl-incantations employed the language of divorce to rid people of the liliths. The liliths also attack children. One of the bowls accuses “Hablas the lilith, granddaughter of Zarni the lilith” of “striking boys and girls” (Montgomery, 168). Another text says that this lilith “destroys and kills and tears and strangles and eats boys and girls” (Montgomery, 193).

Lilith in the Bablyonian Talmud

The few references to Lilith in rabbinic literature point to a figure very much like the female lilith of the incantation bowls. Rabbi Hanina (BT SabbathShabbat 151b) refers to the sexual danger that the lilith constitutes for men: “It is forbidden to sleep in a house alone, and whoever sleeps in a house alone, a lilith seizes him.” Two other references to the lilith point to her physical appearance: she has wings and long hair. Drawings of the liliths or demons on the incantation bowls bear out these details of physical appearance. “Rav Judah said in the name of Samuel: An abortion with the likeness of a lilith, its mother is impure because of the birth, for it is a child, but it has wings” (BT Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.Niddah 24b).

The Alphabet of Ben Sira

Lilith’s image as a dangerous demon persists in the Alphabet of Ben Sira, where she becomes the first wife of Adam (Stern; Yassif 1984). As Scholem (1974) remarks, this tale “sets out to explain the already widespread custom of writing amulets against Lilith.” God created Lilith from the earth after the creation of Adam. They immediately began to fight over who would be on top during sexual intercourse. Lilith said, “We are equal to each other inasmuch as we were both created from the earth.” Lilith then pronounced God’s name and flew away into the air. At Adam’s request, God sent three angels to bring Lilith back, but she refused. According to one version of the tale, she told them that she could not return to her first husband because she had already slept with the “Great Demon.” She told the angels that she was created only to sicken newborn babies and that she had dominion over males until the eighth day (when the boy is circumcised) and over females until the twelfth day after birth. The angels then told her that they would not force her to go back to Adam as long as she agreed to leave the child alone when she saw an amulet inscribed with the angels’ names and forms. Many amulets have been made against Lilith that refer to this tale. For example, Sefer Raziel (Amsterdam, 1701) contains instructions, with drawings, of how to make an amulet against Lilith. Even today, it is possible to purchase amulets made according to this model in Jerusalem shops that sell religious articles.

Lilith in Kabbalah

Lilith became a figure of cosmic evil in medieval The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah. In the thirteenth-century “Treatise on the Left Emanation,” she became the female consort of Samael (Scholem, 1927; Dan). The “Great Demon” of the Alphabet of Ben Sira was given the name of Samael. According to earlier midrashim he had seduced the serpent to evil in the Garden of Eden and he was long identified as the angel of death and the guardian angel of Rome. In the “Treatise on the Left Emanation,” Samael and Lilith emanated together from beneath the Throne of Glory as a result of the sin of the first humans in the Garden of Eden. Their mythological characteristics were further developed in the Zohar (Tishby; Scholem 1974). There, Lilith and Samael emanated together from one of the divine powers, the sefirah of Gevurah (Strength). On the side of evil, the Sitra Ahra (the “Other Side”), they correspond to the holy divine female and male: “Just as on the side of holiness so on ‘the other side’ there are male and female, included one with the other” (Tishby, II: 461). Lilith attempted intercourse with Adam before the creation of Eve, and after the creation of Eve she fled and ever after has plotted to kill newborn children. She dwells in the “cities of the sea” and at the end of days God will make her dwell in the ruins of Rome (Tishby).

In the Zohar Lilith’s demonic sexuality comes especially to the fore. She attempts to seduce men and use their seed to create bodies for her demonic children. The Zohar recommends the performance of a special ritual before sexual intercourse between husband and wife, in which the husband should turn his mind to God and say, “Veiled in velvet, are you here?/Loosened, loosened (be your spell)!/Go not in and go not out!/Let there be none of you and nothing of your part!” (Scholem 1965: 157). She is the seductive harlot who leads men astray, but when they turn to her, she transforms into the angel of death and kills them (Tishby)

The Feminist Lilith

The traditional depiction of Lilith from ancient Mesopotamia through medieval Kabbalah presents an antitype of desired human sexuality and family life. Lilith not only embodies people’s fears of how attraction to others can ruin their marriages, or of how risky childbearing and raising children are, but also represents a woman whom society cannot control—a woman who determines her own sexual partners, who is wild and unkempt, and who does not have the natural consequences of sexual activity, children.

The contemporary feminist movement found an inspiration in this image of Lilith as the uncontrollable woman and decisively changed the image of Lilith from demon to powerful woman. In 1972 Lilly Rivlin published an article on Lilith for the feminist magazine Ms., with the aim of recovering her for contemporary women. The Jewish feminist magazine Lilith, founded in the fall of 1976, took her name because the editors were inspired by Lilith’s fight for equality with Adam. An article in the introductory issue spelled out Lilith’s appeal and rejected the understanding of her as a demon. Since then, interest in Lilith has only grown among Jewish feminists, neo-pagans, listeners to contemporary music by women (highlighted in the Lilith Fair), poets, and other writers. A useful recent book collecting many articles and poems on Lilith, with specific focus on her importance for Jewish women, is Whose Lilith? (1998). As Lilly Rivlin writes in her “Afterword,” “In the late twentieth century, self-sufficient women, inspired by the women’s movement, have adopted the Lilith myth as their own. They have transformed her into a female symbol for autonomy, sexual choice, and control of one’s own destiny.”

Books

Dame, Enid, Lilly Rivlin, and Henny Wenkart, eds. Which Lilith? Feminist Writers Re-create the World’s First Woman. Introduction by Naomi Wolf. Northvale, NJ: 1998.

Montgomery, James. Aramaic Incantation Texts from Nippur. Philadelphia: 1913.

Naveh, Joseph, and Shaul Shaked. Amulets and Magic Bowls: Aramaic Incantations of Late Antiquity. Second edition. Jerusalem: 1987.

Naveh, Joseph, and Shaul Shaked. Magic Spells and Formulae. Jerusalem: 1993.

Patai, Raphael. The Hebrew Goddess. 1967. Third enlarged edition. Detroit: 1990. Chapter Seven is devoted to Lilith.

Scholem, Gershom. On the Kabbalah and its Symbolism. Trans. Ralph Manheim. New York: 1965.

Scholem, Gershom. On the Mystical Shape of the Godhead: Basic Concepts in the Kabbalah. New York: 1991.

Schrire, Theodore. Hebrew Amulets: Their Decipherment and Interpretation. London: 1966.

Tishby, Isaiah. The Wisdom of the Zohar. 3 vols. Trans. David Goldstein. Oxford: 1989.

Trachtenberg, Joshua. Jewish Magic and Superstition. 1939. Reprint, N.Y.: 1970.

Yassif, Eli. The Hebrew Folktale: History, Genre, Meaning. Trans. Jacqueline S. Teitelbaum. Bloomington: 1999.

Yassif, Eli. Tales of Ben Sira in the Middle Ages (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1984.

Articles

“The Alphabet of Ben Sira.” In Rabbinic Fantasies, edited by David Stern and Mark Jay Mirsky, 167–202. Philadelphia: 1990.

Dan, Joseph. “Samael, Lilith, and the Concept of Evil in Early Kabbalah.” In Essential Papers on Kabbalah, edited by Lawrence Fine, 154–178. New York: 1995.

Hutter, M. “Lilith.” In Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, edited by Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter W. van der Horst. Leiden: 1995.

Lesses, Rebecca, “Exe(o)rcising Power: Women as Sorceresses, Exorcists, and Demonesses in Babylonian Jewish Society in Late Antiquity.” JAAR 69 (2001): 343–375.

Levine, Baruch, “The Language of the Magic Bowls.” In A History of the Jews in Babylonia, Vol. 5, edited by Jacob Neusner, 243–373. Leiden: 1970.

Plaskow, Judith. “The Coming of Lilith.” In Religion and Sexism: Images of Women in the Jewish and Christian Traditions, edited by Rosemary Ruether, 341–343. New York: 1974.

Scholem, Gershom. “Lilith.” In Kabbalah, by Gershom Scholem, 356–360. Jerusalem: 1974.

Scholem, Gershom. “New Contributions to the Discussion of Ashmedai and Lilith” (Hebrew). Tarbiz 19 (1947/8): 165–175.

Scholem, Gershom. “The Kabbalah of R. Jacob and R. Isaac, the sons of R. Jacob ha-Kohen” (Hebrew). Madda‘ei ha-Yahadut 2 (1927): 244–264. Publication of “Treatise on the Left Emanation” by R. Isaac ben R. Jacob ha-Kohen.

Scurlock, J. A. “Baby-snatching demons, restless souls, and the dangers of childbirth: medico-magical means of dealing with some of the perils of motherhood in ancient Mesopotamia.” Incognita 2 (1991): 137–185.

Teugels, G.M.G. “The Creation of the Human in Rabbinic Tradition.” In The Creation of Man and Woman: Interpretations of the Biblical Narratives in Jewish and Christian Traditions, edited by Gerard P. Luttikhuizen, 107–127. Leiden: 2000

Websites

http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~humm/Topics/Lilith/lilith.html

An excellent site at the University of Pennsylvania, with many of the original

sources available here, and links to other sites on Lilith.

http://www.lilith.org/

The website of Lilith magazine.

http://www.lilithfair.com/

A website on the music festival Lilith Fair.

http://www.lilitu.com/lilith/

The Lilith Shrine, a personal website of a Jewish pagan with many interesting

links, especially on the contemporary meanings of Lilith.