Learned Women in Traditional Jewish Society

The long-standing idea that women are either not fit to be educated or do not need to be educated has deep roots in Jewish history. Yet in spite of these very real disabilities, there seem always to have been a handful of women in traditional Jewish communities who became educated. These women tend to fall into two categories. The first category, and by far the more common, are women from learned families where there are no sons. In these cases, in order for the father to fulfill the Deuteronomic commandment, he is obliged to teach his daughter. The second category includes daughters from learned families who benefit peripherally from the education of brothers.

Historical Background

The long-standing idea that women are either not fit to be educated or do not need to be educated has deep roots in Jewish history. Beginning with the Hebrew Bible, the primacy of men is a given and women’s status is closely related to their childbearing function. There are, however, some exceptions. Both Deborah and Huldah were prophets and therefore presumably knowledgeable in the law. The matriarchs, although not equal to their husbands, displayed assertive behavior and did not hesitate to manipulate events to fit their own interpretations of God’s will.

Deuteronomy, the latest of the five books of the Pentateuch, states that a man must teach the law of God to his banekha (Deut. 6:8). In the original Hebrew, a language that has no neuter nouns, this word can be read in two ways: “You shall teach it to your children,” assuming the word encompasses both male and female, or the more literal meaning, “You shall teach it to your sons.” There is some evidence that early Palestinian sources interpreted the word banekha more broadly and believed that women could also acquire merit by studying the law (Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah Nedarim 4:3; (Aramaic) A work containing a collection of tanna'itic beraitot, organized into a series of tractates each of which parallels a tractate of the Mishnah.Tosefta Berakhot 2:12; The interpretations and elaborations of the Mishnah by the amora'im in the academies of Erez Israel. Editing completed c. 500 C.E.Jerusalem Talmud SabbathShabbat 3:4). However, the Babylonian scholars strongly disagreed. For those living in societies where women’s inferiority was taken for granted, as it was throughout the Middle East, this ambiguous verse was unlikely to be interpreted in favor of teaching daughters and the education of girls was therefore almost always inferior to that of boys.

With the entrenchment and spread of the The discussions and elaborations by the amora'im of Babylon on the Mishnah between early 3rd and late 5th c. C.E.; it is the foundation of Jewish Law and has halakhic supremacy over the Jerusalem Talmud.Babylonian Talmud and its further interpretations, social inferiority was hardened into law. The sages concluded that women were not bound by positive commandments that had to be performed at specific times. And since women were not obligated to practice the commandments, they did not have to learn them. The exceptions to this generalization pertained to the laws of Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah (ritual purity), candle lighting, and the commandment of During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah (separating a portion of the dough when baking bread, as an offering to God). These commandments were learned at home. There is no evidence of academies for girls or women, either in Palestine or in any of the early Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora communities.

Yet in spite of these very real disabilities, there seem always to have been a handful of women in traditional Jewish communities who became educated. These women tend to fall into two categories. The first category, and by far the more common, are women from learned families where there are no sons. In these cases, in order for the father to fulfill the Deuteronomic commandment, he is obliged to teach his daughter. The second category includes daughters from learned families who benefit peripherally from the education of brothers. These women probably enjoyed a higher than average intelligence, a keen interest in the subjects their brothers were learning, and, in addition, were married off late enough to allow them to benefit from some education before going off to assume the duties of a wife. Most examples of this are found only in the later centuries, with relatively more learned women surfacing in the West than in the East.

There are a variety of reasons for this differential, but a primary cause is the seclusion of Muslim women in the lands of Islam, especialy among the upper classes. The Muslim practice influenced Jews in these communities, and in later centuries it was a common assumption that Jewish women living under Islamic regimes rarely attended synagogue. If a few had access to serious learning in the privacy of their homes, it was rarely documented.

In the Christian West, women were freer to move around the streets and Jewish women followed suit. They were, in general, more active in all aspects of society and it was common for the wives of learned men to be pious and learned. With the Renaissance, learning became more widespread and its effects can be seen in the quality and quantity of literary output authored by Jewish women in sixteenth-century Italy, spreading from there north and east into other Diaspora communities. With the translation of many of the more serious Hebrew works into Yiddish, women gained more access to the knowledge of Jewish law than they ever had before.

Learned Women in the Middle East and in Muslim Lands

The Rabbinic Era

Rabbinic literature occasionally portrays women as approaching rabbis to answer halakhic questions, particularly on the topics of niddah and sexuality (M. Niddah 8:3; BT Niddah 20a-b; BT Nedarim 20b), but they are rarely depicted as learned in their own right. The Babylonian Talmud does occasionally reference the category of an ishah haverah, a woman who knows rabbinic law well, yet they too rely on rabbis to answer halakhic questions in some cases (BT Hagigah 20a) while knowing the law themselves in others (BT Sanhedrin 8b).

These stories of women’s halakhic questions often teach practical halakhah, but are also used on occasion to demean women and their intellectual capabilities. In one story found in the Babylonian Talmud, a “wise woman” asks Rabbi Eliezer (an opponent of women’s Torah study) a question about the interpretation of the story of the Golden Calf, to which he responds, “A woman’s wisdom is only at the spindle” (BT Yoma 66a). A parallel version of this story in the Jerusalem Talmud records a more extreme response: when a wealthy patron of the rabbinic academy asks Rabbi Eliezer a similar question, he replies, “Better the Torah be burned than to be studied by a woman” (JT Sotah 3:4). However, the Jerusalem Talmud seems aware of Rabbi Eliezer’s extremist response, with his son criticizing his father for driving away such a wealthy donor while his students ask, “Rabbi, this one you pushed away with a stick, but what would you explain to us?” — in other words, you sent her away, but her question was valid.

The most famous learned woman in the Talmud is Beruryah, who is depicted across rabbinic literature as knowledgeable and able to engage in rabbinic discourse. She is a composite of two characters mentioned in the Tosefta, one named Beruryah (T. Keilim Metzia 1:3) and the other the unnamed daughter of R. Hananiah b. Teradyon (T. Keilim Kamma 4:9), who both make halakhic rulings. The Babylonian Talmud merges these two characters and names her the wife of Rabbi Meir, depicting her as particularly learned (BT Pesahim 62b) and as engaging in midrashic debate with her own husband (BT Brakhot 10b) or other rabbis (BT Eruvin 53b, Avodah Zarah 18a-b). Scholars differ on whether these rabbinic sources about women reflect real history or a rhetorical construction.

Beyond the academic communities of scholars in Roman Palestine and in Babylonia, there are fewer learned Jews in general and less information about them. Talmudic standards did not sift down to the general population until after the spread of Islam and the strengthening of the Geonate. The Head of the Torah academies of Sura and Pumbedita in 6th to 11th c. Babylonia.Geonim were leaders of the Babylonian academies who began to send out rulings to Jews throughout the Middle East and eventually west into the developing communities of Europe.

The Middle East Under Islam

The Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsa of the Geonim did nothing to change the norms limiting education for girls. R. Hai Gaon (Hai ben Sherira, 939–1038), a tenth-century scholar, ruled that girls must also be taught, but the standard was very different for them. The requirement was simply that they learn the commandments that would allow them to be “kosher women of Israel.” This education was mainly the responsibility of the girl’s mother or other female relative. It usually ended when the daughter left her childhood home to be married, sometimes as early as nine or ten years old.

Reports of learned women that surfaced during the period from 700 to 1200 C.E. were rare and often fragmentary. Documents found in the Genizah suggest that women in Egypt during the Fatimid Empire (969–mid-thirteenth century) were more likely to be educated. Many worked as teachers of children or in girls’ schools, teaching the rudiments of literacy and perhaps some Bible stories and prayers as well as needlework and embroidery. Records show many Jewish women referred to as mu’allimah (Arabic for teacher). From the responsa of Moses Maimonides we know of one woman who was forced to make her living as a Bible teacher in her brother’s academy because her husband failed to support her. We also know of one school, called “The Synagogue of the Women Teachers,” where reading and writing were taught to children between the ages of four and thirteen. However, there is almost no evidence of women reaching the level of learning that was expected of male students. Maimonides, the leading figure in twelfth-century Cairo, disapproved of educating women, and his influence on Judaism proved stronger than the liberal trends in Fatimid society.

Other than in Egypt, there were a few outstanding exceptions to the rule that women were not—and need not be—taught. The earliest of these is Bat ha-Levi (the daughter of the Levite), a learned woman whose name is not known but whose activities were reported in a medieval travel diary. She was the only child of R. Samuel ben Ali (Samuel ha-Levi ben al-Dastur, d. 1194), the Gaon of Baghdad, and lived in the twelfth century. The traveler described in detail how she sat next to an open window and taught her father’s (male) students who listened from the courtyard below. This arrangement served both to preserve her modesty and to prevent the students from being diverted from their studies by her appearance. A eulogy in the form of a poem, written by R. Eleazar ben Jacob ha-Bavli (c. 1195–1250), was believed to be about Bat ha-Levi. In the poem she is described as a woman distinguished by her many virtues and her rare wisdom, but her name is not mentioned. In the writings of a convert to Islam named Shmuel ha-Maghrebi, S. D. Goitein found evidence of educated Jewish women in the same century. The writer described his mother and sisters, natives of Basra (Iraq), as “proficient in the Scriptures and in Hebrew calligraphy,” but made no mention of their knowledge of Jewish law, the ultimate standard for an educated Jew.

The extent of learning achieved by Miriam Benayah of Yemen, a scribe of the fifteenth century, is also unclear, but she was certainly educated enough to be a skilled Hebrew copyist. Miriam, who worked in the family workshop, may have contributed to many books and scrolls. One Torah scroll, however, is unquestionably the work of her hands, since she wrote at the end: “Do not condemn me for any errors that you may find, as I am a nursing woman.”

Perhaps one of the most educated of all the women in the Middle East was Asnat Barazani, who lived in northern Iraq (then Kurdistan) in the sixteenth century and like so many other learned women was an only child in a rabbinic family. Shmuel Barazani, Asnat’s father, clearly had great respect for his daughter’s talents. When he arranged for her marriage to Rabbi Jacob ben Judah Mizrahi, he stipulated that she must be able to continue her studies. After her husband’s death, Asnat Barazani Mizrahi became the head of her father’s academy and taught Torah there.

While the general educational level of women in the Middle East and North Africa remained low, exceptions continually appeared. A late example of a learned woman is Freha bat Avraham bar Adiba, a poet and scholar of the eighteenth century. Born in Morocco, she lived in Tunisia and was killed there when Tunis was attacked and conquered by the Algerians. To honor her memory Freha’s father built a synagogue in her name. He located the ritual bath on the site where her bed once stood, while the Holy Ark marked the place of her library.

Muslim Spain

In Muslim Spain a rare example of a learned woman from the tenth century is the wife of Dunash ben Labrat, the famous grammarian and Hebrew poet. Only a single poem by this woman is extant. It was written when her husband left her to go into exile. Here again, the fact that it was composed in Hebrew suggests a higher level of learning than might be expected, since women were not routinely taught Hebrew. However, nothing is known of this woman’s family or education.

In the following century the wife of the Karaite leader Abu l-Taras, from the city of Toledo, also gained a reputation as an educated woman. Known only by the title al-mu’allima (the teacher), she was knowledgeable in the Karaite version of the law. After the death of her husband, his followers relied on al-mu’allima when they had doubts about what to do.

Qasmuna, a poet who wrote in Arabic, was once believed to be the daughter of the scholar and statesman of Granada, Samuel ha-Nagid (993–1055/56), but new information places her in the early twelfth century. Although Qasmuna probably wrote a good deal of poetry, only a few four-line poems have been found. These are lyrical and follow the style of Arabic poetry in her time. They may have been composed and presented orally and only later written down. Stories about her attest to the fact that her father taught her the art of poetry but there is no evidence that she studied Jewish law or knew Hebrew.

Learned Women in Christian Europe

Northwestern Europe

Diaspora Jewish communities did not become well established in northwestern Europe until the tenth century and any documentation before that time is rare. Examples of learned women do not appear until relatively late in the Middle Ages and these, not surprisingly, are found among the daughters and wives of scholars.

Shlomo ben Yitzhak (c.1040 –1105), better known as Rashi, had three daughters and no sons. It would be reasonable to assume that his daughters, Yokheved, Miriam, and Rachel (also known as Belle Assez), were learned, but there is no definitive evidence for this. Both Yokheved and Miriam married their father’s students and were the mothers of scholarly sons. They also had daughters who, whether formally educated or not, were knowledgeable and astute. Hannah, the daughter of Yokheved and R. Meir ben Shmuel, was quoted by her brother, the famed Rabbenu Tam (Jacob ben Meir Tam, c. 1100–1171), concerning laws about candle-lighting. Elvina (Alvina), the daughter of Miriam and R. Yehudah ben Natan, taught some of Rashi’s customs, learned from her mother, to her cousin R. Yitzhak of Dampierre.

Rashi’s youngest daughter, Rachel, was divorced early and spent a good part of her life in her parents’ home. It was long believed that she wrote at least one legal ruling for her father when he was sick. This assumption was based on a single source, a thirteenth-century work, Shibbolei Ha-Leket. In 2001, the reference to Rashi’s daughter was discovered to be a misprint; the word should have been “grandson” and not “daughter.” This recent correction eliminated the only evidence available for Rachel’s possible erudition.

Women conversant with Jewish law appear among Rashi’s descendents and their spouses, continuing into twelfth- and thirteenth-century France, up until the time of the French expulsion in 1306. One of Rashi’s granddaughters (unnamed) is credited with having taught the women of her community how to perform the commandments to which they were obligated. Rabbenu Tam’s second wife, Miriam, was asked to explain her husband’s customs after his death, and the wife (b. 1305) of R. Yosef ben Yohanan Treibish, another of Rashi’s descendants, clarified obscure passages in the Talmud and explained difficulties in the writings of the Tosafists (school of commentators on the Talmud in France and Germany; twelfth to fourteenth centuries).

Dulcea of Worms (Germany), also believed to be related to Rashi, was highly regarded as a learned woman. She was married to the great Rhineland scholar, R. Eleazar ben Judah (1165–1230), also known as the Rokeah, and was active herself, teaching her own daughters and other women in the community, and presiding over the women’s section of the synagogue.

There were a handful of other women whose opinions on matters pertaining to The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut and women’s commandments have been recorded in various collections of responsa. These include Bellette, sister of R. Isaac ben Menahem the Great (eleventh century), the unnamed widow of R. Isaac ben Samuel of Dampierre (d. c. 1185), and others, all of whose rulings depended on the established customs of male relatives.

Italy

Italy has the distinction of being the site of the earliest Jewish communities in Europe and scholarship was well developed there by the tenth century. However, there is little evidence of learned women until the Renaissance, which began in the late fourteenth century, and it is clear that girls never participated in the formal Jewish education offered to boys in yeshivot. As everywhere among Jews, the principal purpose of the formal education of girls was to teach them to manage a household. But some girls, especially among the more educated or prosperous families, were taught at home.

Paula dei Mansi of Italy was the daughter of Abraham Anau (fl. early thirteenth century) and a member of a distinguished family of scribes who traced their roots back to Nathan ben Jehiel of Rome (Ba’al he-Arukh, 1035–c. 1110). The first evidence of Paula’s scribal and intellectual skills is to be found in a collection of Bible commentaries (1288). While her father wrote the original collection, she added her own explanations and translated the entire work from Hebrew into Italian. Paula also copied a prayer book and added her own explanations. A third work is a collection of laws, written at the request of a relative.

Another woman in Italy who engaged in serious scholarship lived a century later than Paula dei Mansi, although her dates are by no means confirmed. She is Miriam Spira-Luria, daughter of the scholar Solomon Spira (c. 1375–c. 1453). Her name appears in a single document, attributed to Johanan Luria (late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries), who claimed to be one of her descendants. In a work incorporated in a book by Josef ben Gershom of Rosheim (1478–1554), Johanan Luria described Rabbanit Miriam as a teacher who “sat in the yeshivah behind a curtain and taught the law to some outstanding young men.”

As the ideas and ideals of the Renaissance became more widespread, records suggest that some Jewish women, particularly in the upper class, received a better secular education than Jewish women ever had before. A document of the sixteenth century reports that rich young women, both Christian and Jewish, studied poetry, learned classical literature and discussed these writings among themselves. Although the stricter rabbinic authorities regularly condemned this type of education for women, warning that it would corrupt them, it persisted and reached its height in the sixteenth century. The most outstanding of these women, however, always seem to have had a good Jewish education as well.

Both Fioretta da Modena and her sister Diana Rieti were disciplined and dedicated sixteenth-century scholars. Expert in Torah, Mishnah, Talmud, A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash, and Zohar, Fioretta was praised for her learning by her grandson, Aaron Berechiah ben Moses of Modena (d. 1639), a cousin on his mother’s side of Leone Modena (1571–1648). When she was seventy-five she left Italy to continue her studies in Safed but died just as she reached the border of Palestine.

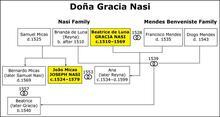

Benvenida Abravanel, from the famous Abrabanel family of Spain, was well educated in both Jewish and secular subjects. As a result of the Spanish Expulsion of 1492, the Abrabanel family immigrated to Naples where Benvenida became tutor to Eleonora, the daughter of the Spanish viceroy. The two women maintained a close relationship long after Eleonora had grown and married the Grand Duke of Tuscany. Benvenida, along with her daughters, was also a generous patron, contributing money for the printing of books and the support of scholars. Among those who benefited from her patronage was the pseudo-messiah David Reuveni (d. 1538?).

In the same century, a few other women’s names appear. Rivkah of Ferrara is mentioned in several records. The daughter of the scholar Jehiel ben Azriel Trabot of Ascoli (d. 1569), she brought her father’s teachings to the attention of his colleagues, who then recorded them for posterity. Anna d’Arpino is named in only one record. According to the roster of the Jewish community of Rome, she was paid for leading the women in prayer in the synagogue on Saturdays and holidays.

A handful of Italian women, most living in the sixteenth century, have been credited as patrons, providing money and encouragement to male scholars and authors. In doing so, they adopted the traditional woman’s role of enabler although they were clearly learned enough to appreciate the talents of the men they sponsored. Sarah of Pisa, Hannah bat Jehiel of Pisa, and Hannah of Rieti are among such women.

By far the best known Jewish women of the Italian Renaissance are Devora Ascarelli of Rome, a sixteenth-century poet and translator, and Sara Coppia Sullam, her slightly later contemporary. Known even in learned Christian circles, Sullam achieved fame, as well as some notoriety, as a poet and writer.

Central and Eastern Europe

As the centuries progress, a handful of women begin to appear in the records without any reference to scholarly men. Among them are Henndlein of Regensburg, referred to as die meistrin (the teacher) in Germany in approximately 1415, with no mention of father or husband. Frommet of Arwyller was educated enough to have reproduced a Hebrew code of laws as a gift to her husband, Samuel ben Moses. Nothing more is known of her. However, evidence of scholarly women who are identified as the wives and daughters of scholars still appear fairly consistently.

R. Israel ben Pethahiah Isserlein of Germany (1390–1460) deemed it important to have an educated wife for his son and engaged a tutor to teach his daughter-in-law Raidel. Isserlein’s own wife, Shondlein, was also quite well educated. She was consulted at least once on a matter of law, by a woman; Shondlein’s responsum, written in Yiddish, is recorded in Leket Yosher: Orah Hayyim by Joseph (Joselein) ben Moses (1423–1490).

About one hundred years later, Bayla Falk of Lemberg (Lwów) daughter of Israel Edels and wife of the prominent rabbi Joshua ben Alexander Ha-Cohen Falk (1555–1614), was a Torah scholar. Her sons praised her, saying that she was “the first to arrive at the synagogue every day …” and that “she would occupy herself with learning Torah.” She was well-versed in Jewish law and is believed to have ruled on a decision concerning when to light holiday candles.

As European Jewry moved east, the population of the Jewish communities of Bohemia, Poland, and Lithuania became more numerous and more and more women in these areas became educated. We know of Roizel Fishels, one of many women printers who worked the Jewish printing presses in Eastern Europe. In 1586 Fishels printed a book of Psalms that had been translated into Yiddish by R. Moshe Standl. As a preface to the book, she composed her own Yiddish poem. Its content suggests that Roizel Fishels was more than just a printer. She was also a teacher and probably understood some Hebrew.

Rivke bas meir Tiktiner was a contemporary of Roizel Fishels, but her level of erudition was certainly higher. Tiktiner was herself a writer and an educator of women. She may even have traveled from town to town preaching to women. Her book on ethics, entitled Meineket Rivkah, was the first book written in Yiddish by a woman. Its contents show that she had a wide knowledge of both Hebrew and Yiddish literature and made frequent reference to the writings of the Bible and the Talmud as well as other religious sources. Her book discusses such topics as raising and caring for children and educating sons. Despite her own superior education, she accepts without comment the centuries-old assumption that girls were not meant to be scholars. Daughters were to be educated only for the purpose of helping to educate their younger brothers.

Later in the sixteenth century, Havvah Bacharach (1580–1651), wife of Isaac ha-Priests; descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses, who were given the right and obligation to perform the Temple services.Kohen, also from Prague, was another of the small number of women who actually entered the erudite culture of learned men. She was part of a dynasty of scholars: the granddaughter of the eminent rabbi, R. Judah Loew ben Bezalel (the Maharal) of Prague (1525–1609), the daughter of Vogele Cohen, and the mother and grandmother of famous rabbis. Havvah Bacharach left no writings of her own but her grandson, Jair Hayyim Bacharach (1638–1702), immortalized her in his book, named Havvot Yair in her honor. Describing her as a teacher as well as a scholar, Jair Hayyim extolled Havvah’s teaching abilities, saying “she taught ... through her comprehension and knowledge ... and she explained in such a manner that all who heard her understood that she was correct.” He added that she taught “Rashi’s commentary on the five books of Moses and the whole Bible and Targum and Apocrypha.”

As more and more of the scholarly Hebrew works were translated into Yiddish, a language much more accessible to women, the number of learned women increased. In the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many women were themselves the translators of Hebrew works. In the late seventeenth century Laza of Frankfurt, the wife of Jacob ben Mordecai of Schworin, translated her husband’s work, Tikkun Shalosh Mishmarot, from Hebrew into Yiddish, adding her own introduction to the Yiddish translation. Other women translated prayers from Hebrew into Yiddish, adding original lines of their own and creating a new genre, the Tkhines. Some of the more famous among these women were Sarah bas-Tovim of Podolia, Leah Dreyzl of Stanislav, and Leah Horowitz of Bolekhov, all from the eighteenth century and all women prayer leaders (firzogerins) in their synagogues. As Hasidism developed and spread, women from this movement joined the ranks of scholarship and leadership. Consistent with the older standard, most of these women—with only a few exceptions—came from the ranks of elite, scholarly families.

The Maid of Ludomir (Hannah Rachel Verbermacher), born in 1815 in Ludomir, Poland, was a rare example of a learned woman who did not come from a rabbinic family but was anxious to learn. She studied The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic works as well as Midrash, Statements that are not Scripturally dependent and that pertain to ethics, traditions and actions of the Rabbis; the non-legal (non-halakhic) material of the Talmud.Aggadah, and ultimately The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah, resisting marriage in order to continue her studies. She gained a modicum of fame among the Jews in her area and counted both men and women among her followers. Ultimately, however, her refusal to marry or to remain with a husband once she finally was persuaded to marry, marked her as a maverick. She ended her life in Palestine, maintaining her own small following until her death in 1892 or 1895.

By the time of Verbermacher’s death, the world of scholarship was opening up to women in Christian Europe and North America and Jewish women were slowly finding their way into secular universities. However, it would be at least another fifty years before the doors of Jewish learning would officially open to them.

Looking back in time, we see that women have often studied privately, ignoring the barriers that were always before them. It is only from the vantage point of modern scholarship that we can recognize that these individual women comprised a community of scholars, even though at the time each woman thought she was an exception.

Abraham ibn Daud. Sefer haQabbalah. Edited and translated by Gerson D. Cohen. London: 1969.

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. “The Educational and Literary Activities of Jewish Women in Italy During the Renaissance and the Catholic Restoration.” Jewish History 5 (1991): 27–40.

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. “Servants and Sexuality: Seduction, Surrogacy and Rape: Some Observations Concerning Class, Gender and Race in Early Modern Italian Jewish Families.” In Gender and Judaism: The Transformation of Tradition, edited by Tamar M. Rudavsky, 81–97. New York and London: 1995.

Adelman, Howard Tzvi. “The Literacy of Jewish Women in Early Modern Italy.” In Women’s Education in Early Modern Europe: A History, 1500–1800. Edited by Barbara J. Whitehead, 133–158. New York and London: 1999.

Ashkenazi, Shlomo. “Learned Women in the Family of Rashi” (Hebrew). Be-Mishur A 27–28, (February 8, 1940): 18–19.

Baskin, Judith. "Educating Jewish Girls in Medieval Muslim and Christian Settings." Making a Difference: Essays in Honor of Tamara Cohn Eskenazi. Edited by David Clines, Kent Richeards, and Jacob L. Wright, 19-37. Sheffield: Phoenix Press, 2012.

Baskin, Judith. “Some Parallels in the Education of Medieval Jewish and Christian Women.” Jewish History 5 (1991): 41–51.

Baskin, Judith. Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing. Detroit: 1994.

Baskin, Judith. Jewish Women in Historical Perspective. Second edition Detroit: 1998.

Baskin, Judith. “The Education of Women and Their Enlightenment in the Middle Ages in the Lands of Islam and Christianity” (Hebrew). Pe’amim 82 (Winter 2000): 31–49.

Baskin, Judith. “Dolce of Worms: The Lives and Deaths of an Exemplary Medieval Jewish Woman and Her Daughters.” In Judaism in Practice: From the Middle Ages through the Early Modern Period. Edited by Lawrence Fine, 429–437. Princeton and Oxford: 2001.

Baskin, Judith and Michael Riegler. "'May the Writer Be Strong': Medieval Hebrew Manuscripts Copied by and for Women." Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women's Studies and Gender Issues vol. 16, no. 2 (2008): 9-28.

Berliner, Abraham. Geschichte der Juden in Rom. Frankfurt am Main: 1893.

Boyarin, Daniel. Carnal Israel: Reading Sex in Talmudic Culture. Berkeley: 1993.

Bromberg, Batya. “Women Who Make New Law” (Hebrew). Sinai 59 (1966): 248–250.

Chetrit, Joseph. “Freha bat Yosef—A Hebrew Poetess of Eighteenth-Century Morocco” (Hebrew). Pe’amim 4 (1980): 84–93.

Idem. “Freha bat Avraham” (Hebrew). Pe’amim 55 (1993): 124–130.

Encyclopaedia Judaica, s.v. “Benayah”.

Fleisher, Ezra. “Dunash ben Labrat and His Wife and Son” (Hebrew). Mehqerei Yerushalayim be-Sifrut Ivrit 5 (1983–1984): 189–202.

Goitein, Shlomo Dov. A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Genizah. 6 vols. Berkeley: 1967–1993.

Idem. “The Jewish Family in the Days of Moses Maimonides.” Conservative Judaism 29:1 (1974): 25–35.

Idem. Jews and Arabs: Their Contacts Through the Ages. Third edition, New York: 1974.

Golinkin, David. The Status of Women in Jewish Law: Responsa (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 2001.

Goodblatt, David. “The Beruryah Traditions.” Journal of Jewish Studies 5 (1975): 68–85.

Grossman, Avraham. Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Europe in the Middle Ages . Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2012.

Halevi, H. S. “Family Life in Israel in the Time of the Geonim” (Hebrew). Ha-Hed 10 (1935): 16–22.

Hassoun, Jacques. “Féminin singulière: En Egypte, du Xe au XVe siècle: Judaisme au feminin.” Les nouveaux cahiers 86 (Autumn, 1986): 5–14.

Kayserling, Meyer. Die Jüdischen Frauen in der Geschichte, Literatur, und Kunst. Leipzig: 1879.

Melammed, Renee Levine. “He Said, She Said: A Woman Teacher in Twelfth-Century Cairo.” AJS Review 22 (1) (1997): 19–35.

Melammed, Uri and Renée Levine. “Rabbi Asnat: A Female Yeshiva Director in Kurdistan,” Pe’amim 82 (2000): 163–178.

Modena, Leon. The Autobiography of a Seventeenth-Century Venetian Rabbi: Leon Modena’s Life of Judah. Ed. and trans. Mark Cohen. Princeton, NJ: 1988.

Petahiah of Regensburg. The Travels of Rabbi Petahiah of Regensburg (Hebrew). Ed. L. Greenhut. Jerusalem: 1967.

Richler, Benjamin. “The Education and Conversation of Rich Italian Daughters During the Renaissance” (Hebrew). Asufot Kiriyat Sefer. 275–278. Jerusalem: 1997–1998.

Roth, Norman. Jews, Visigoths and Romans in Medieval Spain: Cooperation and Conflict. Leiden: 1994.

Stern, Moritz. Regensburg im Mittelalter. Vol. 5 of Die israelitsche Bevölkerung der deutschen Städte: ein Beitrag zur deutschen Stadtgeschichte. Frankfurt am Main: 1935.

Stow, Kenneth, and Sandra Debenedetti Stow. “Donne ebree a Roma nell’eta del ghetto: affeto, dipendenza, autonomia.” Rassegna Mensile di Israel 52 (1986): 63–116.

Taitz, Emily, Sondra Henry, Cheryl Tallan. The JPS Guide to Jewish Women: 600 b. c. e. B 1900 c. e. Philadelphia: 2003.

Wegner, Judith Romney. Chattel or Person? The Status of Women in the Mishnah. New York: 1988.

Weissler, Chava. Voices of the Matriarchs: Listening to the Prayers of Early Modern Jewish Women. Boston: 1998.

Yuval, Yisrael Yaakov. The Spiritual Activities of the Jews of Germany (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1988.