Kurdish Women

Jews lived in Kurdistan for 2,800 years until a mass migration to Israel in the 1950s. This Jewish community’s ancient roots and relative seclusion in the Kurdistan region fostered unique religious, cultural, and linguistic practices. The community spoke an Aramaic that is closely related to ancient Aramaic, as well as Kurdish in larger society. Kurdish and Jewish life and culture became so intertwined that popular folk stories accounting for Kurdish ethnic origins connect them with the Jews. The country’s harsh geography and climate contributed to the establishment of the economic structure of Kurdish Jewry’s small rural communities, which relied on traditional farming. Women and men both worked in the fields, and, despite the patriarchal nature of the society, women were treated with a high level of respect.

Introduction

The history of the Kurdish Jewish community began well before the destruction of the First Temple and continued for many generations. Ancient tradition has it that Jews were settled in Kurdistan 2,800 years ago, part of the Ten Tribes dispersed by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser. Kurdish Jews identify themselves as amongst those described in the Prophets: “…the king of Assyria captured Samaria. He deported the Israelites to Assyria and settled them in Halah, at the [River] Habor, at the River Gozan…” (2 Kings 17:6), places which are in fact within the Kurdistan region.

The first to highlight the Kurdish Jews’ tradition of antiquity was the medieval Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela (second half of twelfth century), who visited Kurdistan in the year 1170. He describes finding over one hundred Jewish communities, including the 25,000 strong community of Amadiya, for whom Aramaic was still a spoken language. Kurdish Jews called their language—actually Aramaic mixed with some Persian, Turkish, Kurdish, Arabic, and Hebrew words—“Lishna Yahudiyya” (the Jewish language) or “Lashon ha-Targum” (language of the Targum) and referred to themselves as “Anshei Targum” (People of [the language of] the Targum). Indeed, their use of an ancient form of Aramaic (formally called Suriyani, i.e., “Assyrian”), closely related to the Aramaic of the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, gives further credence to the tradition of their community’s ancient origins.

Scholars agree that by the beginning of the second century C.E. Judaism was firmly established in central Kurdistan. During the fourth and fifth centuries Kurdistan was a fertile ground for conversion to Christianity, yet most Jews maintained their commitment to the Jewish faith. Records have been found from the Place for storing books or ritual objects which have become unusable.genizah of Kurdistan that date back to the sixth century.

In the twelfth century, when Benjamin of Tudela visited, both Kurdistan as a whole and its Jewish community in particular were at a high point in their history. Benjamin describes financially and religiously vibrant communities, with many synagogues and rabbis. But the community’s stability and prosperity soon deteriorated. When the Spanish-Jewish poet Judah al-Harizi visited in 1230, he spoke of splendid synagogues—full of ignorant worshippers. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, no records at all exist of the Jews of Kurdistan. During this two-hundred-year period, the Jews, like their non-Jewish neighbors, may have been occupied primarily with escaping the destruction of the Mongolian conquerors.

In 1534, Kurdistan became part of the Ottoman Empire, remaining under Turkish rule until the end of World War I. From the sixteenth century onwards, the main written legacy of the Kurdish Jewish community—primarily the writings of its rabbis—has been preserved. These documents reflect a society, many of whose members lived in simplicity and poverty, yet which also supported yeshivot and Jewish scholarship. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw both Jewish and non-Jewish populations reduced, in some cases even decimated, as a result of armed conflicts between the Turkish government and local tribal leaders. But the Jews remained a relatively large group in Kurdistan—many villages were populated entirely by Jews—until their immigration to Israel in the mid-twentieth century.

Throughout the centuries, the Jews of Kurdistan rarely lived in peace and tranquility with the Muslims; their lives were subject to major political and economic instability, since they were frequently forced to move suddenly or to pay huge taxes for protection. On the other hand, their geographical isolation throughout three thousand years allowed them to be spared the stormy periods that affected other nations, as well as the Jews. This isolation also helped to preserve the distinctive religious, social, and cultural characteristics of the Jewish communities in Kurdistan, though it concomitantly cut them off from the centers of Jewish society for most of their history. Thus, while it was the only place in the Jewish world where Aramaic remained a living language, Kurdistan hosted a population with little knowledge of Rabbinic Judaism, though they religiously practiced the few Jewish customs and A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvot passed on from previous generations. Though in certain periods of relative prosperity Jewish learning flourished, illiteracy was common; only the leaders of the community and a few others were literate.

The country’s harsh geographic and climatic conditions also contributed to the establishment of the unique economic structure of Kurdish Jewry’s small rural communities, which were the only ones in the Jewish world that maintained traditional farming as a major source of livelihood. Although Kurdish Jews spoke Aramaic within their own community, in commerce within the larger society they spoke Kurdish. Many aspects of Kurdish and Jewish life and culture became so intertwined that some of the most popular folk stories accounting for Kurdish ethnic origins connect them with the Jews.

After World War I, modernization and industrialization began to influence the community—a process accelerated after Kurdish Jews’ immigration to Israel en masse in 1950–1951, when many of the traditional customs ceased to exist or were given different interpretations. However, the Kurdish Jews continue to live in their own neighborhoods in Israel and still celebrate Kurdish life and culture, festivals, costumes, and music in symbolic ethnic forms.

The Kurds are a patriarchal society, yet Kurdish Jewish women enjoy much more freedom than their Jewish sisters in other traditional Jewish communities and they are far more independent than their counterparts among Kurdish, Turkish, Iranian, or Iraqi Muslim women. The relationship between husband and wife is much more relaxed than that in other communities. Jewish women worked in the field with their husbands and rarely had to cover their faces with a veil. Though the superior-inferior relationship existed, as in any patriarchal society, Jewish Kurdish men treated women with great respect, due to the women’s contribution to the wealth and hard work of the extended family.

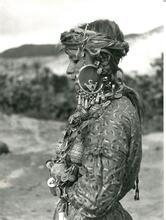

Kurdish Jews did not differ in their clothing from the rest of the population. The men wore turbans, circling them with colorful scarves. They wore a wide top with large wide sleeves, wide trousers, and a wide belt around their waist. The women wore long striped gowns, with wide scarf cloths around their heads. They decorated their arms, hands, and legs with gold and silver jewelry. Thus in their appearance and behavior the Jews blended completely and utterly with the local indigenous population. During celebrations and parties there was no separation between men and women; holding hands, they danced folkloric dances together. Furthermore, though women worked very hard from morning to night, they found time to enjoy bathing together in the river, singing and joking—a kind of ritual that takes many hours.

In the seventeenth century the relative freedom of Kurdish women in their community led to the scholarly achievements of Asnat Barazani, the daughter of the well-known Rabbi Samuel Barazani (1630), who founded many Judaic schools and seminaries in Kurdistan. She was referred to as Lit. (from Aramaic teni) "to hand down orally," "study," "teach." A scholar quoted in the Mishnah or of the Mishnaic era, i.e., during the first two centuries of the Common Era. In the chain of tradition, they were followed by the amora'im.tanna’it, the feminine form of the customary term for a Talmudic scholar. Asnat became the head of the prestigious Judaic academy at Mosul.

Life Cycle

Birthing

During pregnancy—and especially during the first—a woman receives love, attention, and respect. Because the pregnant woman attempted to conceal her pregnancy for reasons of modesty, she stayed indoors during most of the nine months. Numerous beliefs, customs, and rituals accompanied the pregnancy. It was quite common for the woman and her relative to seek a fortune-teller in order to find out the sex of the baby. The belief was that anything a woman sees or feels during conception or pregnancy would influence the character of the child, its looks, behavior, and well-being. If the pregnant woman fancied a certain food and did not get it, the baby’s body would have a mark in the shape of that particular type of food. Therefore all her fancies and wishes had to be fulfilled. While women as a rule rarely drank alcohol, they believed that if a pregnant woman drank wine her baby would be born handsome and fair. An anxious pregnant woman was made to drink water that had been kept exposed on the roof overnight and received starlight. Prior to her drinking, hot skewers were put in the water, to provide her with strength to overcome her fear. A pregnant woman was not allowed to go outside during a lunar eclipse because it might affect the part of the child’s body that was exposed to the eclipse and cause deformities. In the case of a woman who suffered from several miscarriages or lost many of her children, the belief was that there was an evil eye or witchcraft influencing her and therefore snake skin or threads of red, green, black, and white were wound around her waist while the names of certain demons were recited. There was a strong belief that performing this ceremony would ensure that the birth would proceed without any problems. The birth was performed by a traditional midwife (with no medical training), with the help of elderly women of the family. Midwives were fully trusted and well respected by the community.

If a husband dies childless, Jewish law demands that his widow marry his brother in Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).Levirate marriage to carry on the deceased’s name. If the eldest brother-in-law did not want her, his younger brother had to marry her, and if he was too young, she had to wait for him. However, this custom was not strictly observed. Usually the halizah ceremony was performed, releasing the widow from the levirate tie and freeing her to marry someone else.

The birth of males was important for the perpetuation of the family. The birth of females evidently created tension, particularly in the husband’s family, and there was a tendency for the husband to blame his wife. The birth of boys reflected the father’s social status and masculinity and increased his self-esteem and self-importance. Women also preferred boys because they brought fame and elevated their status in the eyes of the family, particularly in the eyes of their husbands. The announcement of the birth of girls to the father was delayed and hushed, but news of a boy’s birth was immediately passed on to the father, even if he already had many sons. The news spread very fast and in no time all the neighborhoods knew of the happy occasion. The different responses are variously accounted for by referring to various facts: that there are no religious or other ceremonies accompanying the birth of a girl, that sons bring their wives into the family while girls leave the family, and that it is easier to find a wife for a male even if he is very old, while it is very hard to find a husband for a young woman if she is about to reach the age of twenty. As she gets older her chances of finding a husband become slimmer, so she becomes a burden on her family and in particular on the older brothers, who have to care for her. There is a saying that expresses the position of the girl: “A girl is like a beautiful apple. Despite its beauty, the longer you leave it the less tasty it becomes, it loses its vitality, and in the end it becomes rotten.”

Marriage

Formally, the father was the master of his family. Although the birth of girls was not as welcome as the birth of boys, the bride-price custom, whereby the father of the bride actually received money for his daughter (as if the husband were buying her), meant that the birth of girls was not considered a burden on the family, even though it was less desired. Girls were married at the age of thirteen or fourteen and boys at the age of seventeen.

Age, beauty, and health were important attributes that increased a female’s chances of attracting a husband from a good family. It was highly unusual for a man to marry into a class lower than his own, and this occurred only if the bride was remarkable for her beauty. A man liked to show his wealth through his wife, and this was evidenced both by the amount of gold with which a man covered his wife and by her healthy looks. A woman had to look after her jewelry and wear her gold and silver on every occasion. It was by the amount of gold he bestowed on her that a man demonstrated his love, affection, and appreciation.

Usually parents began to look for a prospective bride within their extended families. Cousin marriages were preferred among all Kurds, including the Jews. If this was not possible, men sought their brides from the extended family and most marriages were endogamous. Once the right bride was found, the couple would be introduced to each other in the company of the families. Formally the matchmaking had to receive the consent of the father, but from interviews it appears that the father would not give his consent without his wife agreeing to the choice. Many parents promised their daughters at a very early age, even at the age of six or seven. Amongst the Iraqi and Turkish Kurds, the bride-price custom was common. Marriages were contracted after the bride-price was agreed upon and this was formalized with a handshake. Once the terms of the agreement of the marriage contract were decided, the kiddushin ceremony was conducted and the father of the bride received the bride-price (money or goods) from the groom or his father. A divorced Kurdish Jewess could remarry but her bride-price would be low or waived, depending on the circumstances. In the final analysis most women could marry and have a family, something that could not be said of the Iraqi Jewess.

In many cases the father of the bride-to-be gave the bride-price to his daughter to use in order to buy material for her clothes and household goods, though formally these had to be provided by the husband. In the event of conflict or if the woman wished to divorce her husband without any good reason, her family had to repay the bride-price. On the other hand, if a man wished to divorce his wife without any apparent reason, he could not demand the bride-price but would have to provide for her welfare until she remarried. He also had to pay her the sum of money stipulated in the Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah (marriage contract). As a result, many men who were not happy with their wives but still wanted to retain all the property and money they had accumulated usually took second wives rather than divorcing their first wives. Such an act caused enormous tension and friction in the household, with conflicts and fights between the children of both women over the inheritance. Furthermore, the community did not encourage divorce. Usually, when a man wished to divorce his wife, the two parties would get together and attempt to settle the conflict before approaching the rabbi. If this was not successful, they would go to an influential member of the community whose opinion they all valued and he would act as an arbitrator, usually managing to solve the conflict and prevent the divorce. Only if the differences between the couple could not be bridged did they approach a rabbi. Very few divorces are recorded and several of them were the result of adultery. The compromise was for the man to take a second wife and for the woman to stay married and have a roof over her head.

It was not uncommon for a man’s parents to buy him a wife. If both parties agreed to the terms, they performed the kiddushin (betrothal) ceremony. This was followed a few months later by the wedding ceremony, enabling the bride to prepare her clothing and linens in the interim. It was customary for the girl to embroider all her bed linen and clothing. This began to change with the exposure to modernity, even in the period prior to the immigration to Israel. Thus, the kiddushin and marriage ceremonies were performed together, as is now customary in Israel.

The wedding celebration began early on Monday morning and continued for seven days, during which the entire community was invited to bridegroom’s house. During the first two days the relatives came to see the bridegroom’s parents. Early on Thursday morning the bridegroom’s friends arrived to be with him, and on the evening of that day the crowd marched from the house of the bridegroom to the house of the bride’s parents to bring the bride from her parents’ house to that of the groom. The decorated bride rode on a colorfully decorated horse accompanied by musicians, singers, and the singing crowd, all the way to her future parents-in-law. Before she entered the house, the bridegroom’s family slaughtered a sheep as atonement for the bridegroom and bride. From then on, the celebration began and generous hospitality was provided.

After the wedding ceremony both parties were anxious as to whether the couple would be able to perform the act of intercourse. While the newlyweds entered the bridal chamber everyone waited outside, eating and drinking, until it was announced that the couple had consummated the marriage. The couple was not allowed to leave the room before successfully performing the act of penetration, for fear of witchcraft, which is believed able to prevent the newlyweds from having intercourse. Prior to the wedding ceremony adults explain to the couple—and particularly to the man—how to successfully perform the act of penetration. If the couple stayed more than half an hour in the room, those outside would knock on the door to find out what the difficulties were. When intercourse had been successfully performed, the bridegroom opened the door and let everyone— particularly his mother—see the bloodied sheet. This was followed by ululating, singing and joyful cries of happiness, while the band commenced playing. The custom was to keep the bloodied sheet as evidence of the bride’s virginity in the event of conflicts between the two families. The marriage concluded with seven days of celebration, during which the couple was not allowed to leave the house for fear of witchcraft.

Gifts were presented at a special ceremony on the first Saturday night after the wedding night. The master of ceremonies announced to the couple the details of the donors and their presents. On the first Saturday after the wedding the bride hosted all her women friends for lunch and presented them with gifts. On the second weekend, she invited both families to her house.

After marriage the young couple moved in with the husband’s parents, as was appropriate in a rural farming society whose members are poor. Living in the same household saved expenses and all members of the extended family gathered food, particularly in the harvest period, when all hands were needed.

Division of Labor

The woman was responsible for all domestic duties, but most of all she had to acknowledge her husband’s superiority, accept his position as the head of the family and obey him. He was in charge of all the activities outside the domestic sphere, religious ceremonies and communal activities. In the home he sat at the head of the table and was the first to receive his food, which would be the biggest portion. Although there was thus a strict division of labor in the home, all the family members, including the wife, worked together in the field.

Education

The behavioral characteristics of the Jewess in Kurdistan were the result of a combination of the traditional local customs of the indigenous population and Jewish religious laws. In this society women’s needs and feelings were given some consideration, due in part to the woman’s contribution to the family workforce. Nevertheless her main duties were childbearing, serving her husband’s needs, and educating her daughters to manage household duties when they married.

The Mandate for Palestine given to Great Britain by the League of Nations in April 1920 to administer Palestine and establish a national home for the Jewish people. It was terminated with the establishment of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.British Mandate did not bring socio-economic prosperity, modernity, and secularization as it did to the Iraqi urban Jews, since the Jewish Kurds were isolated geographically, socially, and culturally from their Iraqi co-religionists. As in the Iraqi community, the majority continued to object to educating girls.

In general the hakhamim (rabbis) did not invest in educating the young because they were busy performing other demanding tasks such as ritual animal slaughter and performing circumcisions of Muslims. In any case, very few were themselves literate. Boys learned in Lit. "room." Old-style Jewish elementary school.heder and girls learned only the Shema Yisrael prayer. From their mothers, sisters, and grandmother girls learned how to perform all household duties and conduct themselves as wives and mothers. As early as 1906 the Alliance Israélite Universelle opened schools for boys and girls, as well as many other facilities for educating and fostering progress among the Jewish Kurds. Non-Jewish Kurds also benefited vastly, since children were accepted into these schools regardless of their religious affiliation. Operations of the Alliance continued until soon after the establishment of Israel. However, very few girls studied in these schools for more than three or four years. The majority of women did not study.

Occupation

As already mentioned, the Kurdish Jews were distinct from the rest of the Jewish world—farming the fertile land and keeping sheep, working in the fields and vineyards from sunrise to sunset. Every evening, women of the extended family and their neighbors would gather to help each other clean the rice, sift the wheat, and bake the bread, all the while singing, chatting, and laughing. During harvest time all the members of the family worked together, including the women. Prior to the immigration to Israel, the majority of the Jews continued to engage in farming as a major source of income, but supplemented it with occupations such as dressmaking, weaving, painting, shoemaking, trading small goods, and bartering. Some seventy families from Zakho excelled in shipping woods and cargo from Kurdistan down the rivers to the arid areas. Walter Fischel (1949) found that in 1936 many Jewish farmers who were poverty-stricken, particularly in years of drought, were forced to sell their daughters because of the famine. There were incidents in which creditors took farmers’ daughters for their sons in lieu of money owed to them. In this time period in Kurdistan, Jewish girls were considered an attractive commodity in exchange for goods.

Jews and Non-Jews

Conversion to Islam was not uncommon. In many cases Jews who converted refused to divorce their wives. Due to the fear of their becoming Woman who cannot remarry, either because her husband cannot or will not give her a divorce (get) or because, in his absence, it is unknown whether he is still alive.agunot, Rabbi Yoseph Haim made a Regulation supplementing the laws of the Torah enacted by a halakhic authority.takkanah to protect women which stated that every man had to write in the Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbah that should he change his religion the kiddushin would be null and void. Thus the women’s right to remarry were not abused by men who decided to convert. As the condition of Jews improved the number of conversions declined dramatically. Shimon Marcus (1964) tells of a not uncommon incident where a marriage was contracted between families, the bride-price was paid, and the engagement took place, but the girl changed her mind and refused to marry the man. For his part, he refused to divorce her. Thereupon the woman threatened to convert to Islam and marry a non-Jew. This threat led to such community pressure that the groom finally granted the woman the bill of divorce.

Generally speaking the Jews had good relations with the Muslims and Christians except for one problem. Kurds loved Jewish women, found them very beautiful and attractive, and desired to marry them. As a result there were many incidents in which Muslims abducted girls and married them. Horrified families guarded their daughters closely, particularly if the girls were young and very good looking. Once a girl was abducted her family could do little to bring her back and the chances of her being found were very slim.

Kurdish Women in Israel

The first group of Kurdish Jews settled in Jerusalem in 1812. Later many also settled in Jaffa, Tiberias, Safed, and Bet Shean, working mainly at farming in the agricultural settlements. The majority of Kurdish Jews who arrived in Israel before World War I came from four parts of Kurdistan: the area of the Turkish city of Diyarbakhir, the mountainous area of Tigris and Euphrates in the north of Iraq, the Kermanshah District of Iran, and the Orumiyeh lake and the city of Tibriz in the Persian district in Azerbaijan. The immigrants who arrived from Iraq via Syria (particularly those from Zakho) integrated very successfully into the agricultural scene, and by the thirties a chain migration was established when the population of many Kurdish villages immigrated to Israel. In 1910 the Jewish Colonial Association attempted to settle Kurdish families in the agricultural settlement of Sejera, near Tiberias. They established agricultural settlements like those in Kurdistan, populated only by Jews from Kurdistan, such as the villages of David Alroy, Kefar Azariah, Kefar Uriah, and many others. In 1935 the population of Kurdish Jews from the Iraqi area totaled eight thousand souls, the majority of whom lived in Jerusalem. After the declaration of the state of Israel, the majority of Jews from the Iraqi part of Kurdistan immigrated to Israel with the mass migration of over 125,000 Jews from Iraq. In 1950 they suffered from the Muslims and had to seek shelter in Teheran until the time was ripe for the Jewish Agency to transfer them to Israel. This was followed by a mass migration of the Jews from the Iranian part of Kurdistan; entire villages were vacated as their population walked hundreds of kilometers to the Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah center in Teheran, whence they were transferred to Israel.

Once in Israel, many formed farming settlements similar to those in Kurdistan. There is a large group in Jerusalem and in other, smaller cities. The women worked in crafts, cleaning, cooking, and other services. Because entire communities moved together with no major change in their socio-cultural structure, the community as a whole and women in particular did not go through major changes or extreme culture shock. Further, unlike the Iraqi women, who were not accustomed to working outside the home, Kurdish women acted as the right hand of their husbands, quickly adapting to life in Israel.

At first the transition from a traditional to a western society did not bring major changes in the functions of the Kurdish family. The division of labor went through gradual changes, as did the position of women. Coming from poverty-stricken areas of Kurdistan, they were prepared to work at every type of occupation. This was particularly true of the women, who were accustomed to working outside the home and for whom it was quite natural to continue working the land. Women worked at many jobs in order to provide for their families. They never complained, but after working from dawn to late afternoon returned home to care for home and family. In time, modernity began to influence the younger generation and women began to take an active part in decision-making. There was a gradual decline in the birthrate and a rise in women’s age of marriage, which resulted in smaller families, a narrowing of the average age difference between husbands and wives and a dramatic decrease in the number of kin marriages.

The girls who arrived in Israel at the age of twelve or more did not go to school because they had to work to help support their family. However, with the introduction of compulsory education for males and females alike up to the age of fourteen, the families had to obey the law. Improved education brought more women into the workforce, resulting in professionalism and an increase in their rights in society. Furthermore, a 1977 law made education compulsory to the age of eighteen. The marriage age is now higher. Israeli family laws protect women’s welfare in the home. Compulsory military service has made women more independent. All these factors contributed fundamentally to a change in the position of Kurdish women, who now have fewer children. Since many of them live in a Kurdish homogeneous ethnic population, inter-ethnic marriages rarely occur. In general young people not only choose their own partners but also undergo a period of courting so that they can get to know each other. Selecting one’s own partner is a function of Western society, concerned with individual rights. The bride-price custom ceased to exist after a number of years in Israel. The extended family remains important for Kurdish women, but not to the same degree as in Kurdistan. As to their beliefs, Susan Sered (1993) in her study of Yemenite and Kurdish women in Israel showed that, though mainly illiterate and excluded from formal religious practices, the women were expert in rituals designed to safeguard the well-being of their extended families. By analyzing their rituals, experiences, and non-verbal gestures, Sered discovered strategies these women have developed to overcome the patriarchal institutions and create their own “little tradition.”

There is still an explicit division between the sexes with regard to work and the professional occupational role is still viewed mainly as a masculine prerogative. Most Kurdish women do not see any contradiction between their role as housewives and their work outside the home. As for decision-making, men already in the country of origin took their wives’ opinions seriously and in Israel this is even more the case.

Only in the last generation have the women begun to be exposed to modernization processes. This is due to the fact that the majority lived in fairly homogenous ethnic groups and were not exposed to other ways of life. On arrival to Israel in the early 1950s the host society and the policy makers “wanted to demonstrate their superiority and they decided for the Kurds in which places to live, establishing villages for them in deserted far-away places isolated from modern centers of activity” (a Kurdish interviewee). Thus Kurdish Jews were once again isolated from the surrounding society and kept in ignorance of it. As a result, it took this ethnic group much longer than others to take advantage of the opportunities offered by modern city life.

Conclusion

The transition to modern society has given more power to women. The decline in the birth rate—the average family today has approximately three children—has also played a major role in improving the welfare of women. The Kurdish woman continues to move toward increased freedom of the individual from parental control, particularly in the last two decades. As Sami Smooha (1978) noted, there is a “growing democratization in respect to sex and age differentiation which took place among Orientals during the last two decades.” In the words of a Kurdish university student interviewee, “Today the woman is independent and is able to fulfill her desire and realize her potential. She is more aware of modernization and takes advantage of modern life as much as she can. Furthermore, even though Jewish women in Kurdistan were respected and their contribution was valued, and they were quite strong, here in Israel she exercises her rights and there is more equality between men and women. In the past a man did not dare ask his wife for help openly, everything was done quietly. Now he needs help too and he can ask his wife to support him emotionally.”

In recent years there has been a revival of symbolic ethnicity among this ethnic group and women play an important part in this process. For example, in Kiryat Malakhi, a development town where there is a large population of Kurds, they have established a performing dance group that has frequently represented Israel at folkloric festivals abroad. Furthermore, in Jerusalem, where there is an attempt to revive Kurdish folk music, there is a choir that sings Kurdish folk songs in the Kurdish language.

English

Ben-Zvi, Yizhak. The Exiled and the Redeemed. Translated from the Hebrew by I. A. Abbady. Philadelphia: 1957.

Brauer, Erich. The Jews of Kurdistan: An Ethnological Study. Edited by Raphael Patai. Detroit: 1993.

Cohen, Haim J. The Jews of the Middle East, 1860–1972. New York and Toronto: 1973.

Filsinger, Eric E. “Love, Liking, and Individual Marital Adjustment: A Pilot Study of Relationship Changes within One Year.” International Journal of Sociology of the Family 13, no. 1 (1983): 145–157.

Fischel, Walter. “The Jews of Kurdistan,” Commentary 8, no. 6 (1949).

Gale, Naomi. “From the Homeland to Sydney: Kinship, Religion, and Ethnicity among Sephardim.” Ph.D. thesis, University of Sydney, 1988.

Idem. “Love and Marriage, Past and Present: The Case of the Oriental Jews in Sydney.” International Journal of Sociology of the Family 24 (1994): 61–86.

Hartman, Moshe. “The Role of Ethnicity in Married Women’s Economic Activity in Israel.” Ethnicity 7, no. 3 (1980): 225–255.

Izady, Mehrdad R. The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Cambridge, MA: 1992.

Katz, Jacob. “Traditional Society and Modern Society.” In Jewish Societies in the Middle East: Community, Culture and Authority, edited by Shlomo Deshen and Walter P. Zenner, 35–48. Washington, D.C: 1982.

Layish, Aharon and Samuel Shaham. “Islamic Law in the Middle East.” The Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (1991): 1–29.

Neusner, Jacob. Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism in Talmudic Babylonia. New York: 1986.

Patai, Rafael. Family, Love and the Bible. London: 1960.

Idem. The Vanished World of Jewry. London: 1981.

Sabar, Yona. The Folk Literature of the Kurdistani Jews. New Haven: 1982.

Smooha, Sammy. Israel: Pluralism and Conflict. London: 1978.

Yona, Mordechai. Kurdish Jewish Encyclopedia, Vol. 1. Miami: 2003.

Hebrew

Amedi, Yitzhak. “The Customs of Kurdish Jews.” In Hithadshut: The Journal of the Kurdish Jews in Israel 7 (2000): 168–189.

Bar-Yosef, Rivka. “Household Management in Two Types of Families in Israel.” In Families in Israel. edited by Leah Shamgar-Handelman and Rivka Bar-Yosef, 169–196. Jerusalem: 1991.

Ben-Arieh, Yehoshua. “The Jewish Settlements in Erez Israel.” In The History of the Jewish Community in Eretz-Israel since 1882, edited by Moshe Lissak and Gavriel Cohen, 75–142. Jerusalem: 1989.

Ben-Ya’acob, Avraham. Jewish Communities in Kurdistan. Jerusalem: 1981.

Ben-Zvi, Yizhak. The Lost Jewish Tribes. Tel Aviv: 1963.

Gavish, Haya. “The Immigration of the Jews of Zakho in Iraqi Kurdistan.” Master’s thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1990.

Marcus, Shimon. “The History of the Jews of Kurdistan”. Mahanaim (1964): 93–94.

Melammed, Uri and Renee Levine-Melammed. “Rabbanit Asenath: The Head of the Yeshiva in Kurdistan.” In Pe’amim: Studies in the Culture Heritage of Oriental Jewry 82 (2000): 163–178.

Sabar, Yona. “The History of the Jews in Kurdistan”. In Hithadshut: The Journal of the Jews of Kurdistan (1990): 51–56.

Idem. “Historical Introduction.” In The Jews of Kurdistan: Daily Life, Customs, Arts and Crafts, by Ora Shwart-Be’eri. Jerusalem: 2000.

Sered, Susan. Women as Ritual Experts: The Religious Lives of Elderly Jewish Women in Jerusalem. Ramat-Gan: 1993.

Shimoni, Baruch. “Life Histories: The Jews of Zakho in Iraqi Kurdistan”. MA thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem: 1992 (also in Hithadshut: The Journal of the Kurdish Jews in Israel 7 (2000): 129–144).

Shimoni, Haviv. “The History of the Jews of Kurdistan”. In Hithadshut: The Journal of the Kurdish Jews in Israel 7 (2000): 95–100.

Ya’acov, Ya’acov. “The Status of Kurdish Jewish Women in Kurdistan.” In Hithadshut: The Journal of the Kurdish Jews in Israel (2000): 321–322.

Yona, Mordechai., “Marriage and Wedding Ceremonies.” In Hithadshut: The Journal of the Kurdish Jews in Israel. (2000): 195–199.