Holocaust Studies in the United States

Jewish American women have made contributions to the field of Holocaust studies in a variety of areas, including general history, women and gender, children, literary criticism, autobiography and biography, curriculum development, religious studies, sociology, psychoanalytic theory, biomedical ethics, and archive and museum curatorship. These scholars come to the study of the Holocaust with diverse experiences, questions, and concerns. However, they all approach the subject with compassion and a profound sense of responsibility to the victims. Many of these scholars are university professors, including Deborah E. Lipstadt, Nechama Tec, and Sidra Dekoven Ezrahi. Although not all female scholars specifically study women, they generally agree that women do need to be accounted for in the study of the Holocaust.

Female American Scholars

Holocaust studies is a dynamic and diverse field of research that embraces various approaches toward the study of the Holocaust. Jewish American women have made critical contributions to this field in a variety of areas, including general history, women and gender, children, literary criticism, autobiography and biography, curriculum development, religious studies, sociology, psychoanalytic theory, biomedical ethics, and archive and museum curatorship. Jewish American women have contributed original research and have reshaped the way the Holocaust is studied through innovative theoretical and methodological approaches. They come to the study of the Holocaust as Jews, as women, and as Americans. With each of these roles and experiences they bring different concerns and questions. Some of these scholars are survivors or refugees or are the daughters of survivors or refugees. Some were born in the United States, some came to the United States during or after the war. Many have focused exclusively on the study of women.

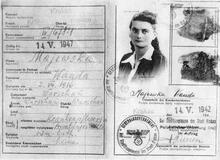

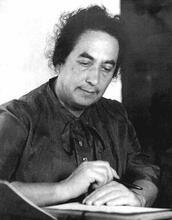

The earliest historical treatments were general overviews that put the Holocaust in its political and social historical context. Lucy Dawidowicz is the best-known American Holocaust historian and also one of the earliest female historians of the Holocaust. She was a professor of history at Yeshiva University in the area of Holocaust studies and wrote extensively on the subject. Her The War Against the Jews: 1933–1945 (1975) examines the Holocaust in terms of its historical context, investigates the Jewish response to the Nazis’ Final Solution, and ultimately explores why the world did not prevent this systematic slaughter.

Historian and author Lucy S. Dawidowicz (1915 - 1990) was a controversial figure not only because of her opinions about Jewish life and history but also because of her methodology. She was not afraid to immerse herself in the world of her people, believing her analyses could combine passion and objectivity.

Institution: American Jewish Historical Society.

Nora Levin is another early contributor to Holocaust studies. Levin was an instructor at Gratz College and is best known for The Holocaust: The Destruction of European Jewry, 1933–1945 (1968), a general history of the Holocaust. Although more recent scholarship has critiqued much of Dawidowicz’s and Levin’s work, these scholars are important because they are Jewish American women who made early and significant contributions to a field that previously had been male-dominated.

Since Dawidowicz and Levin, female American scholars have consistently expanded Holocaust studies by bringing new questions and evidence to the field. Historian Sybil Milton (1941–2000) was a prolific scholar who expanded the boundaries of the historical study of the Holocaust. Milton studied the Holocaust as a major event of the twentieth century within the context of Central European and German history. As such, the Holocaust includes but is not limited to the Nazi genocide of European Jews. Milton continued to explore new dimensions of the Holocaust through her historical consideration of gender issues, non-Jewish children, the fate of Gypsies, postwar trials, and the problem of memorials in Germany and Austria. Milton also critically evaluated the role of visual images as historical evidence and analyzed art and photography as tools of interpretation. She explored this topic in numerous articles and books, including The Camera as Weapon and Voyeur: Photography of the Holocaust as Historical Evidence, where she fully developed her analysis of the role of photography as historical evidence and the problems that visual images pose for interpretation of the Holocaust. Milton was senior historian at the United States Holocaust Museum Research Institute and worked extensively as an archival and exhibit consultant for museums, archives, and memorials in the United States, Europe, and Canada.

Responses to the Holocaust

Holocaust studies also include responses to the Holocaust. Deborah E. Lipstadt is the foremost scholar working in the area of Holocaust denial and has done extensive research into American responses to the Holocaust by examining the public discourses during and after the event. Lipstadt is Dorot Professor of Modern Jewish Studies at Emory University and serves on the United States Holocaust Memorial Council’s executive committee. Lipstadt designed the section of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum that is devoted to the American response to the Holocaust. She is also chair of the museum’s education committee. Lipstadt’s Beyond Belief: The American Press and the Coming of the Holocaust, 1933–1945 (1986) examines how the American press reported on the Nazi persecutions of Jews in Eastern Europe and provocatively explores what the American public knew about the persecution of European Jewry between 1933 and 1945.

Lipstadt’s Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (1993, 1994 National Jewish Book Honor Award winner) contains the most comprehensive examination of Holocaust denial and deniers. Lipstadt’s work has expanded and reformulated the historical study of the Holocaust by positioning the problem of denial and deniers as a central issue. The work also transformed her from “academic” to “celebrity,” when David Irving, whom she accused in the book of being a Holocaust denier, sued her and her British publisher for libel. Since the British courts, unlike their American counterparts, place the onus for a libel case on the writer rather than on the subject (in the United States, the subject must show that the reference to him/her is false, while in Britain, the writer must prove the veracity of what he/she wrote), Lipstadt would have to prove that Irving was lying, or conversely, demonstrate the truth of what he alleged to be a lie—that the “events” he claimed never happened had actually occurred. Thus a libel suit became the case that put the reality of the Holocaust on trial. When she won the case, Lipstadt received the gratitude of Holocaust survivors, the admiration of the Jewish public and the approbation of the Israeli government for her contribution to the battle against Holocaust denial.

Sociological Approaches

Sociological approaches to the study of the Holocaust have become increasingly important to our understanding of the social phenomenon that occurred prior to, during, and after the Holocaust. Helen Fein (b. 1934) contributed original research and analysis to both Holocaust studies and genocide studies, combining historical and sociological methods of analysis and interpretation. She was executive director of the Institute for the Study of Genocide and the first president of the Association of Genocide Scholars, an international organization that she helped to found in 1995. Fein’s Accounting for Genocide: National Responses and Jewish Victimization During the Holocaust (1979) challenges the questions that have been asked about the Holocaust. Rather than focusing on the success of the Nazi destruction of European Jewry, Fein analyzes the rate of survival of Jews according to nation-states and proposes understanding the differences of survival rates in terms of national responses. As part of this innovative analysis, Fein examines the empiric responsibility and moral accountability of churches, Jewish leadership, and the Allies in the destruction of European Jewry. Fein extends her analysis of the Holocaust to account for other racial victims such as Gypsies and begins to develop a theoretical account of ideological genocide in the twentieth century. Since then, Fein has continued her work in the area of genocide, connecting it to violation of human rights.

Nechama Tec (b. 1931) was professor of sociology at University of Connecticut, Stamford, and a scholar at the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. She is a member of the advisory boards of the Braun Center’s Foundation to Sustain Righteous Christians and the Braun Center for Holocaust Studies. In Defiance: The Bielski Partisans (1993), using original research, Tec challenges the historical paradigm of Jew as victim during the Holocaust by examining the phenomenon of Jews as rescuers—Jews who rescued others even while they were themselves in danger of being killed. By focusing on the Bielski partisans, Tec critically demonstrates that not all Jews were passive victims. Although her early interest was in Christian rescuers, Tec became interested in Jews who rescued other Jews. Tec makes clear that her own experiences of being a hidden child in Poland (where she lived under an assumed name, pretending to be a Catholic) prompted her interest in the wartime relationships between the rescuers and the rescued. Tec’s and Fein’s reputations testify to the growing centrality of sociological analysis in the historical study of the Holocaust.

Women and the Holocaust

The study of women and the Holocaust is one of the fastest growing areas of research within Holocaust studies. Although not all female scholars are working specifically in the area of women, there is a consensus among them that women do need to be accounted for in the study of the Holocaust. Including women is, Sybil Milton argues, simply a matter of good scholarship. After all, women represented half of the population and half of those who perished. Women also ask questions about the Holocaust that have not been posed by male scholars. Early male scholars often focused on the history of the Holocaust as if it were only the history of men in the Holocaust. Female scholars have opened up the study of the Holocaust to include accounts of women’s roles and experiences and have made the consideration of gender a basic category of analysis.

Joan Ringelheim (b. 1939) was director of the Department of Oral History at the Research Institute of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and pioneered in the study of women and the Holocaust, convening the first conference on the subject in 1983. Her interest in the study of the Holocaust was also influenced by her family’s experience of the Holocaust. Ringelheim’s paternal grandparents and eighty-eight paternal relatives lost their lives in Poland during the Holocaust. Growing up, she had long discussions with her father about prejudice, racism, and the Holocaust. Ringelheim underlines the significance of gender as a category of analysis. However, Ringelheim also is concerned about the assumptions we use when we assert the importance of gender when we study the Holocaust. In her article “Women and the Holocaust: A Reconsideration of the Research” (1985), she demonstrates that the assumptions we make about gender color the questions we ask and influence the conclusions we draw about women and the Holocaust. Ringelheim is concerned that feminist questions about women, intended to challenge traditional understandings of women as passive and oppressed, have a tendency to interpret women’s responses to the Holocaust in the best possible light. For example, if we look at women’s responses to the murder of their children in terms of their ability to “mother” other persons, this positive interpretation obscures the reality of the victimization of women by the Nazis.

Marion Kaplan (b. 1946) is professor of history at Queens College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York as well as a consultant to the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. Kaplan’s interest in Holocaust studies was shaped by being the daughter of German Jewish refugees. She describes her own work as an attempt to enrich both Jewish history and German history with evidence and questions from both areas. By studying Jewish and non-Jewish German women, Kaplan demonstrates in The Jewish Feminist Movement in Germany: The Campaigns of the Jüdischer Frauenbund, 1904–1938 (1979) that women shared common experiences. At the same time, in Jewish Life in Nazi Germany (1997) Kaplan highlights the distinctive experiences of women as Jews under Nazism. Kaplan argues that Jewish women were doubly stigmatized by antisemitism and sexism.

Many scholars combine their interest in the area of women and the Holocaust with other areas of study. Judith Tydor Baumel (b. 1959) is an Israeli-American scholar who works in the area of women and the Holocaust but is also interested in collective memory. Baumel has raised important questions about the role of women during and after the Holocaust through her work on Jewish refugee children and on survivors. She is lecturer in the department of Jewish History at the University of Haifa. She describes her focus on the Holocaust as stemming from a natural response to her family’s history, with her work on refugee children and postwar Jewish experiences being prompted by her family’s experience of the Holocaust. Together with Walter Laqueur, Baumel is associate editor of the Yale Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (1998). Ringelheim, Kaplan, and Baumel are exemplary representatives of a growing number of Jewish American female scholars who are not only challenging the way we understand women and the Holocaust but also are transforming the ways we study and think about the Holocaust.

Deborah Dwork (b. 1954) has contributed important research into the history of the children of the Holocaust. Dwork’s mother was born in the United States, but her mother’s adopted sister was born in Poland and was a survivor of the Holocaust. Dwork grew up with an awareness of how the Holocaust had affected her family. Although there has been tremendous research into the Holocaust, there had been no historical study of children. In her classic, Children With a Star: Jewish Youth in Nazi Europe (1991), Dwork argues that it is the history of the children that particularly and painfully underlines the horror of the Holocaust: It is the children who show that there can be no excuse for the Nazi Judeocide. Dwork has organized her research into patterns of children’s experience during and after the war. By studying the lives of the children during the Holocaust, Dwork also explores how adults, particularly women, were active in trying to hide and protect children. Dwork is Rose Professor of Holocaust Studies at Clark University. She also works with the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous, where she has developed an educational resource for teachers of the Holocaust. She is a consultant for the Anti-Defamation League, is on the national advisory board for Facing History and Ourselves, and works with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and other organizations centrally concerned with the future disposition of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Literary Analyses

In addition to the historical study of the Holocaust, Holocaust studies includes literary criticism and biography and autobiography. Austrian-born Ruth Kluger (b. 1931; formerly known by her married name, Ruth Angress) has made contributions to Holocaust studies through her award-winning autobiography and her literary criticism. Her autobiography begins with her earliest memories of being a child before the war, describes her experiences in the camps, and ends after the war when she was twenty-one. Kluger became an American citizen in 1952. Kluger’s experiences during the Holocaust in Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Gross-Rosen have had a major impact on her scholarship. She explains that her experiences have led her to be more critical and less empathetic about German literature, creating a tension that she sees as essential to her analysis of the literature. The literature must be analyzed in light of the historical reality of the Holocaust. Kluger was the first chair of German at both Princeton University and the University of Virginia. She recently retired as professor of German at the University of California at Riverside and is currently on the council of the Fritz Bauer Institute of Holocaust Studies in Germany.

Sidra Dekoven Ezrahi (b. 1942), is associate professor of comparative Jewish literature in the Institute of Contemporary Jewry and the Rothberg School at the Hebrew University and lectures regularly at Yad Vashem. Born and educated in the United States, Ezrahi was among the first scholars to investigate and critically analyze Holocaust literature. Her powerful analysis has had important implications for both Holocaust studies and literary analysis. Her By Words Alone: The Holocaust in Literature (1980) interprets Holocaust literature by examining cross-cultural types of imaginative responses to the Holocaust. Since then, Ezrahi’s most recent work examines the problems of representation in Holocaust literature.

Sara R. Horowitz (b. 1951) is associate professor of English and comparative literature and director of the Jewish Studies program at the University of Delaware. Horowitz’s work focuses on issues of gender, genocide, and Jewish memory. She describes her work as examining Holocaust literature as a form of deep meditation. In terms of gender, Horowitz perceives significant difference in the ways men and women are represented in Holocaust literature. Horowitz argues persuasively that these differences often correspond to differing gendered experiences of the Holocaust. In her recent Voicing the Void: Muteness and Memory in Holocaust Fiction (1997), Horowitz examines a wide variety of Holocaust fiction by authors of different nationalities, genders, and styles in terms of muteness—the painful inability to account meaningfully for and respond to the horrors of the Holocaust.

Jewish American women come to the study of the Holocaust with diverse experiences, questions, and concerns. However, they all come to the subject with compassion and a profound sense of responsibility to the victims.

Baumel, Judith Tydor. Kibbutz Buchenvald: Survivors and Pioneers (1997), and Unfulfilled Promise: The Jewish Refugee Children in the United States 1934–1945 (1990), and A Voice of Lament: The Holocaust and Prayer. (Heb.) (1992).

Dawidowicz, Lucy S. From That Time and Place: A Memoir, 1938–1947 (1989), and The War Against the Jews: 1933–1945 (1975).

Dwork, Deborah. Children With a Star: Jewish Youth in Nazi Europe (1991).

Dwork, Deborah, and Robert Jan van Pelt. Auschwitz, 1270 to the Present (1996).

Ezrahi, Sidra Dekoven. By Words Alone: The Holocaust in Literature (1980), and “The Grave in the Air.” In Probing the Limits of Representation: Nazism and the Final Solution, edited by Saul Friedlander (1992), and The Holocaust and the Limits of Representations (1994).

and “Representing Auschwitz.” History and Memory 7, no. 2 (Winter 1996).

Fein, Helen. Accounting for Genocide: National Responses and Jewish Victimization During the Holocaust (1979), and The Persisting Question: Social Contexts and Sociological Perspectives of Modern Antisemitism (1987), and “Reading the Second Text: Meanings and Misuses of the Holocaust.” In The Challenge of Shalom: The Jewish Tradition of Peace and Justice, edited by Murray Polner and Naomi Goodman (1994).

Grossmann, Atina. Reforming Sex: The German Movement for Birth Control and Abortion Reform, 1920–1950 (1995).

Horowitz, Sara. “Memory and Testimony in Women Survivors of Nazi Genocide.” In Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing, edited by Judith Baskin (1994), and “Mengele, the Gynecologist, and Other Stories of Women’s Survival.” In Judaism Since Gender, edited by Miram Peskowitz and Laura Levitt (1997), and Voicing the Void: Muteness and Memory in Holocaust Fiction (1997).

Kaplan, Marion. The Jewish Feminist Movement in Germany: The Campaigns of the Jüdischer Frauenbund, 1904–1938 (1979), and Jewish Life in Nazi Germany (1997).

Kluger, Ruth. Katastrophen: Uber Deutsche Literatur (1994), and Weiter Leben: Eine Jugend (1992).

Kremer, Lillian S. Witness Through the Imagination: Jewish-American Holocaust Literature (1989).

Levin, Nora. The Holocaust: The Destruction of European Jewry, 1933–1945 (1968).

Lipstadt, Deborah. Beyond Belief: The American Press and the Coming of the Holocaust, 1933–1945 (1986), Denying the Holocaust: The Growing Assault on Truth and Memory (1993), and History on Trial: My Day in Court with David Irving (2005).

Milton, Sybil. The Camera as Weapon and Voyeur: Photography of the Holocaust as Historical Evidence (forthcoming); The Holocaust: Ideology, Bureaucracy, and Genocide: The San Jose Papers. Edited with Henry Friedlander (1980), and In Fitting Memory: The Art and Politics of Holocaust Memorials (1991), and “Women and the Holocaust: The Case of German and German-Jewish Women.” In When Biology Became Destiny: Women in Weimar and Nazi Germany, edited by Renate Bridenthal, Marion Kaplan, and Atina Grossmann (1984).

Ringelheim, Joan. “The Unethical and the Unspeakable: Women and the Holocaust.” The Simon Wiesenthal Annual 1 (1984): 69–87, and “Women and the Holocaust: A Reconsideration of the Research.” Signs 10, no. 41 (1985): 741–761, reprinted in Jewish Women in Historical Perspectives, edited by Judith Baskin (1991).

Tec, Nechama. Defiance: The Bielski Partisans (1993), and Dry Tears: The Story of a Lost Childhood (1984), and In the Lion’s Den: The Life of Oswald Rufeisen (1990), and When Light Pierced the Darkness: Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland (1990).