Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse created innovative sculptural forms using unconventional materials such as latex and fiberglass and gave minimal art organic, emotional, and kinetic features. She scorned good taste and the decorative, creating sculptures out of repeated units which embodied opposite extremes. These extremes were born from the extremes of her own life; Hesse’s family escaped Nazi Germany in 1939, and her mother committed suicide in 1946 when Hesse was just ten years old. While in Germany on a sponsored work stay in 1964, Hesse had her artistic breakthrough – she turned away from painting and began experimenting with plaster and string. Idiosyncratic placement was one of Hesse’s contributions to sculptural structure; her large fiberglass and latex works are recognized as major works of that artistic era.

Eva Hesse is recognized as one of the most innovative and powerful artists to emerge in the 1960s New York art world. She created new sculptural forms using eccentric materials such as latex and fiberglass, and has become known for giving minimal art organic, emotional, and kinetic aspects. Her material and formal inventions, with their sensuous and emotional extremes, were balanced by an active verbal intelligence that won her the respect of the art community—as her warmth and wry humor won her many friends.

Extreme Contradictions

Both Hesse’s life and art were fraught with extreme contradictions. Almost impossibly demanding of herself, she was nevertheless completely open to the unknown. She scorned good taste and the decorative, believing the authentic was never reached through subject matter, messages, or programs. The dynamic of her work was not expression, but discovery. She wrote, “It is my main concern to go beyond what I know and what I can know.” She pulled new meanings from deep in her psyche and gave them new formal structures that related to order, yet also resisted it. Usually these structures involved repeated units—the same but not exactly the same—that embodied opposite extremes: order/chaos, hardness/softness, directness/irony, horror/humor, mechanical/organic. The absurd is as inescapable in her work as it is in Samuel Beckett’s. Her subject, not merely her expression, is abstract. Her central theme is existence itself: the possibility of identity in a deranged world.

Early Life & Education

Eva Hesse was born in Hamburg, Germany, on January 11, 1936 to educated Jewish parents, Wilhelm Hesse, a criminal lawyer, and the artistic Ruth Marcus House. In 1938, to escape the Nazis, she and her sister Helen (later Helen Charash), who was three years older, were separated from their parents. The next year the family made it to New York. There her mother, severely depressed, took her own life in 1946, a year after her divorce from Wilhelm Hesse and his subsequent remarriage to Eva Nathanson.

The legacies of the Holocaust and of her disastrous family history were the subjects of the horrible fears and anxieties which Hesse battled throughout her life. Creative and “difficult” in her youth, she found much of her artistic identity outside her formal education. She graduated from the High School of Industrial Arts in 1952. She then attended Pratt Institute of Design for one and a half years and Cooper Union for three years, graduating in 1957. In 1959, she received her B.F.A. from the Yale School of Art and Architecture and immediately moved back to New York. There she continued an intense regimen of drawing and painting, attending exhibitions, and reading art history and twentieth-century literature. She also began to establish herself among her peers, including Sol LeWitt and Mel Bochner. In 1961, Hesse married the well-known American sculptor Tom Doyle.

Finding Her Artistic Identity

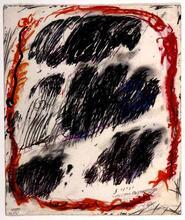

In an extraordinary group of small ink and gouache works on paper she produced in 1960–1961, forms emerged that uncannily predicted her great late sculptures. Translucent and dark, fragile and potent, abstract or all-but-abstract—these images of boxes, circles, and strings claimed her ambiguous structural and emotional territory.

Over the next few years, Hesse worked urgently to extract her artistic identity from painting, but it resisted her needs. It was in the drawings from 1962 to mid-decade that she made the strange linear and spatial discoveries that she later developed in grids and serial treatments.

From early adulthood to the end of her life, Hesse kept diaries in which she examined her struggle for authentic psychological and artistic identity. Her analytic intelligence, constantly judging, worked uphill against her debilitating terrors to achieve the high aesthetic ground her own standards and ambition required. The encouragement of her peers and friends, particularly Sol LeWitt, helped—both in New York and when she accompanied Doyle to Germany on a sponsored work stay in 1964–1965.

Breakthrough & Recognition

In Germany, it was Doyle’s suggestion which provided the connection Hesse had sought so desperately: to forget painting and work with plaster and string, to make things with her hands. This sparked her breakthrough into the bright wound string reliefs with found objects and jazzy titles. These in turn led, after Hesse was back in New York, to the monochromatic or gradated black and gray sculptures with more wound string, wrapped forms, and such non-art materials as net bags, rubber tubing, and dangling cords.

The year 1966 was disruptive; Hesse’s father died and her marriage came to an end. Yet in terms of her art, it was excellent. Major new works by Hesse were featured both in “Abstract Inflationism and Stuffed Expressionism” at the Graham Gallery and in Lucy Lippard’s “Eccentric Abstraction” at the Fischbach Gallery, and new drawings were shown at the Visual Arts Gallery.

By 1967, though still haunted by fear and panic, Hesse had arrived at a period of high accomplishment and recognition. Black or gray grids of circular forms, often with strings dangling from their centers, and rows of rectangular boxes were her dominant motifs. These evolved eccentrically into, for example, raw latex floor pieces with the round units jumbled and out of order. This sort of idiosyncratic placement was one of Hesse’s contributions to sculptural structure: similar but not identical units placed neither too close nor too distant, neither too ordered nor too disordered. Such placements in relation to wall or floor grids or to rows—yet unchartable—characterized the sculpture in her major exhibition, “Eva Hesse: Chain Polymers” at the Fischbach Gallery, and in the historic “9 at Leo Castelli” show at the end of the year. Her large fiberglass and latex works have been recognized by museums and writers worldwide as major works of the era.

End of Life

Despite being diagnosed with a brain tumor and undergoing operations in April and August of 1969 and in March of 1970, Hesse overcame her physical weakness with a tremendous appetite for both art and life. She continued to think and work energetically to the end.

Eva Hesse died on May 29, 1970, in New York City.

Barrette, Bill. Eva Hesse Sculpture. New York: Timken Publishers, 1989

Cooper, Helen A., with Maurice Berger et al. Eva Hesse: A Retrospective. Exhibition Catalog. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992

David, Catherine and Corinne Diserens. Eva Hesse. Exhibition Catalog. Valéncia: IVAM Centre Julio González, 1993

Frank, Elizabeth. Eva Hesse Gouaches 1960–1961. Exhibition Catalog. New York: Robert Miller Gallery, 1991

Johnson, Ellen H. Eva Hesse: A Retrospective of the Drawings. Exhibition Catalog. Oberlin, Ohio: Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1982

Kozloff, Max. Eva Hesse Paintings. Exhibition catalog New York: Robert Miller Gallery, 1992

Lippard, Lucy R. Eva Hesse. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992

Nemser, Cindy. Art Talk: Conversations with Twelve Women Artists. New York: Scribner, 1975

Nixon, Mignon, ed. Eva Hesse. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002

Obituary. NYTimes, May 30, 1970, 23:5

Reinhardt, Brigitte, with Naomi Spector et al. Eva Hesse: Drawing in Space—Paintings and Reliefs. Stuttgart, Germany: Cantz, 1994

Shearer, Linda, with Robert Pincus Whitten. Eva Hesse: A Memorial Exhibition. Exhibition Catalog. New York City: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1972

Sussman, Elisabeth, ed. Eva Hesse. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002.