Esther: Bible

In the biblical book named after her, Esther is a young Jewish woman living in the Persian diaspora who finds favor with the king, becomes queen, and risks her life to save the Jewish people from destruction when the court official Haman persuades the king to authorize a pogrom against all the Jews of the empire. Written in the diaspora in the late Persian/early Hellenistic period (fourth century B.C.E.), the Book of Esther is a Jewish novella that deals with the enduring issues of preserving Jewish identity and ensuring survival amid cultural pressures and hostile enemies in a foreign land.

The Path to Becoming Queen

Esther first appears in the story as one of the young virgins collected into the king’s harem as possible replacements for Vashti, the banished wife of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes I, reigned 485—465 B.C.E.). She is identified as the daughter of Avihail (Esth 2:15) and the cousin and adopted daughter of Mordecai, from the tribe of Benjamin (Esth 2:5–7). Not much is revealed about her character, but she is described as beautiful (2:7) and obedient (2:10), and she appears to be pliant and cooperative. She quickly wins the favor of the chief eunuch, Hegai, and, when her turn comes to spend the night with the king, Ahasuerus falls in love with her and makes her his queen. All this takes place while Esther keeps her Jewish identity secret (Esth 2:10, 20).

After Esther becomes queen, her cousin Mordecai becomes involved in a power struggle with the grand vizier Haman the Agagite, a descendant of an Amalekite king who was an enemy of Israel during the time of King Saul (1 Sam 15:32). Mordecai refuses to bow before Haman, and this so infuriates Haman that he resolves not only to put Mordecai to death, but also to slaughter his entire people. He secures the king’s permission to do this, and a date is set, Adar 13 (this episode determines the date of the festival of Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim, a popular Jewish festival). When Mordecai learns of Haman’s plot, he rushes to the palace to inform Esther, weeping and clothed in sackcloth (Esth 4:1–3).

Esther Saves the Jews from the Plot Against Them

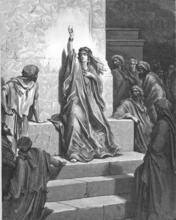

At this point in the story, Esther’s character comes to the fore. When she first learns of Haman’s plot and the threat to the Jews, her reaction is one of helplessness. On pain of death she cannot approach the king without being summoned, and the king has not summoned her in thirty days, implying that she has fallen out of favor (Esth 4:11). However, following Mordecai’s insistent prodding, she resolves to do what she can to save her people, ending with the ringing declaration “After that I will go to the king, though it is against the law; and if I perish, I perish” (Esth 4:16). The pliant and obedient Esther has become a woman of action.

Esther appears unsummoned before King Ahasuerus, who not only does not kill her but promises to grant her as-yet unarticulated request. In a superb moment of understatement, Esther asks the king to a dinner party (Esth 5:4). The king, accompanied by Haman, attends Esther’s banquet and again seeks to discover her request, which she once more deflects with an invitation to another dinner party. Only at the second dinner party, when the king is sufficiently beguiled by her charms, does she reveal her true purpose: the unmasking of Haman and his plot. She reveals, for the first time, her identity as a Jew and accuses Haman of the plot to destroy her and her people. The volatile king springs to the defense of the woman to whom he was indifferent three days earlier, Haman is executed, and the Jews receive permission to defend themselves from their enemies, which they do with great success (Esther 7–9). The book ends with Mordecai elevated to the office of grand vizier and power now concentrated in the hands of Esther.

Unique Features of the Book of Esther

Like the books of Daniel or Tobit, the Book of Esther raises questions about how to live as a Jew in diaspora. However, the Book of Esther is unique in two important respects. First, although Mordecai has an important role and finishes the story at a very high rank, it is ultimately Esther, a woman, who saves her people. This choice of a female hero serves an important function in the story. Women were, in the world of the Persian diaspora as in many other cultures, essentially powerless and marginalized members of society. Even if they belonged to the dominant culture, they could not simply reach out and grasp power, as a man could; whatever power they could obtain was earned through the manipulation of the public holders of power, men. In this sense the Jew living in a foreign land could identify with the woman: he or she too was essentially powerless and marginalized, and power could be obtained only through one’s wits and talents. But, as the actions of Esther demonstrate, this can be done. By astutely using her beauty, charm, and political intelligence, and by taking one well-placed risk, Esther saves her people, brings about the downfall of their enemy, and elevates her kinsman to the highest position in the kingdom. Esther becomes the model for the Jew living in diaspora or exile.

Second, the Book of Esther differs from other biblical diaspora stories by the marked absence of God or any overt religious elements. Fasting is observed, though not accompanied by prayer, and Esther calls for a fast among the Jews at precisely the time they would have been observing Passover.

The apparent irreligiosity of the book has been a source of puzzlement as well as critique for many of its readers. Although very popular among the Jewish people, especially because of its connection with the festival of Purim, its status as a holy book was called into question due to its lack of the divine name of God. The rabbis were troubled by Esther’s failure to live as a Jew: she has sexual intercourse with and marries a Gentile, lives in the Persian court, and does not follow Jewish dietary laws (the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, tries to remedy this by adding prayers and repeatedly invoking God, as well as having Esther declare that she loathes her present lifestyle). In addition, Esther has been taken to task by both female and male commentators for her apparent willingness to participate in Persian harem customs, and by Christian commentators for her evident bloodthirstiness in destroying Gentiles (Esth 9:1–15). All of these criticisms continue to provoke discussion about the purpose of the book.

The Purpose of the Book of Esther

The purpose of the Book of Esther is open to different interpretations. It can be understood as commending human responsibility instead of misguided dependence on God: the Jews in the book must take matters into their own hands to preserve their existence, rather than wait for God to act. Alternatively, despite not mentioning God directly, the many apparent “coincidences” in the book have often been seen as alluding to God working behind the scenes of history. Still another interpretation of the book views its message as an implied critique of diaspora Jews who have become assimilated to the culture around them, disregarded traditional Jewish law, and neglected God, yet are nevertheless destined to overcome their enemies.

The character of Esther and her story serves as a source of reflection for Jewish men and women living in diaspora, both in the time the book was written and down through the centuries to the present day. It confronts readers with questions that are asked anew in each generation: What does it mean to live as a Jew? Can one be Jewish without God or religious observance? What are Jews to do in the face of hostility and the threat of genocide? The contemporaneity of these issues helps to account for the enduring popularity of the book, and Esther herself, in the Jewish community.

Amsellem, Wendy. “The Mirror Has Two Faces: An Exploration of Esther and Vashti.” JOFA Journal 4 (2003): 7. See: https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/vashti-esther-a-feminist-perspective/

Berlin, Adele. The JPS Bible Commentary: Esther. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2001.

Carruthers, Jo. Esther Through the Centuries. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008.

Fox, Michael V. Character and Ideology in the Book of Esther. Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans 2001.

Levenson, Jon, D. Esther: A Commentary. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox 1997.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000.

Reimer, Gail Twersky. “Eschewing Esther/Embracing Esther: The Changing Representation of Biblical Heroines.” In Talking Back: Images of Jewish Women in American Popular Culture, edited by Joyce Antler, 207-19. Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 1997.

White, Sidnie A. “Esther.” In Women’s Bible Commentary, edited by Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, 124–129. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1992; expanded edition, 1998.

White, Sidnie A.. “Esther: A Feminine Model for Jewish Diaspora.” In Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel, edited by Peggy L. Day, 161–177. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989.

Zornberg, Avivah. “Esther—Mere Anarchy Is Loosed upon the World,” in The Murmuring Deep, 108-109. New York: Schocken, 2011.