Eastern European Immigrants in the United States

Forty-four percent of the approximately two million Jewish immigrants who arrived in the United States between 1886 and 1914 were women. Immigrant daughters found work in the garment industry, while wives and mothers worked primarily inside the home, tending to boarders and assisting their husbands. Wife desertion was common, and the need to work often thwarted young women’s educational aspirations. Nevertheless, mothers and daughters acted confidently in the political realm, galvanizing the Jewish labor movement – daughters took great interest in left-wing politics, while mothers organized community-based kosher meat boycotts and rent strikes. American Jewish social reformers feared that this disreputable behavior would encourage antisemitism, but they also recognized the potential of immigrant women as agents of assimilation, given the centrality of the mother in Jewish family life.

Of all Jewish immigrants to the United States from 1886 to 1914, forty-four percent were women, far more than for other immigrant groups arriving during the heyday of mass immigration. The more than two million Jews from the Russian Empire, Romania, and Austria-Hungary who entered the United States in the years 1881 to 1924—when the American government imposed a restrictive quota system—came to stay. Only 7 percent chose to return to Europe, as opposed to about 30 percent of all immigrants. Jewish immigrants intended to raise American families. Ashkenazi (European) Jewish culture and American values as conveyed by social reformers as well as by advertising, and the economic realities of urban capitalist America, all influenced the position of women in immigrant Jewish society in America. Jewish immigrant women shared many of the attributes of immigrant women in general, but also displayed ethnic characteristics.

Jewish Immigrants in the American Economy

Immigrant Jews, both female and male, arrived in America with considerable experience of urban life in a capitalist economy. Unlike many other migrants to America’s shores, they had not been peasants in the old country. In the northwest section of Russia’s Pale of Settlement, the western provinces to which Jews were restricted, they accounted for 58 percent of the total urban population. In the Pale as a whole, Jews constituted thirty-eight percent of those living in cities or towns, though only 12 percent of the total population. Similarly, more than a third of the population in urban communities in Galicia were Jews, as were twenty percent in Romania’s provincial capitals. Women worked alongside men, supporting their families primarily through petty commerce, selling all kinds of produce in the marketplace, and also through artisan trades such as shoemaking and tailoring. In the small number of traditional families where husbands devoted themselves to studying Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, women bore the major responsibility as breadwinners for their families.

Settling primarily in the cities of the East Coast, in crowded, tenement-filled districts that were often called “ghettos,” many Jewish immigrants worked in the burgeoning garment industry, in shops often owned by descendants of an earlier immigrant wave of Central European Jews. Others took advantage of their commercial background in the market towns and cities of Eastern Europe to become peddlers, hoping that their entrepreneurial skills would lead to prosperity. Although immigrant Jewish males arrived in the United States with less cash than the average immigrant, they inserted themselves into the economy largely as skilled workers and peddlers, while most newcomers began their working lives in America as unskilled laborers.

Family Dynamics

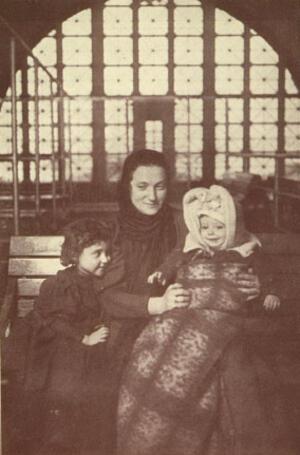

Even though the mass migration of Jews from Eastern Europe was a “family migration,” the process of leaving the Old World for the New often temporarily disrupted families. Jews engaged in chain migration, in which one member of an extended family secured a place in the new country and then bought a ticket for siblings so that they could settle in America. Oftentimes, married men set out in advance to prepare the way economically and planned for their wives and children to join them once they were settled. Sometimes the delay in reuniting the family stretched into years, compelling women to raise their children alone and to take on the full responsibility of arranging a transoceanic voyage. The outbreak of World War I, for example, left Rachel Burstein with her three children in the Ukrainian town of Kamen-Kashirski while her husband labored in America, having returned there from a prolonged visit with his family that began in 1913. Only after six and a half years of separation did Rachel and her children succeed in reaching Ellis Island, where they were quarantined for two weeks, before coming to their final destination of Chelsea, Massachusetts. Hershl, now Harry, Burstein made no effort to meet them at Ellis Island or at the train station in Boston. As their daughter, Lillian Burstein Gorenstein, then age twelve, wrote in her memoirs years later, “On both sides were lines of people waving. … No one waved to us” (169).

Once settled in America, women and men worked together to sustain their families. Because Jewish men were more successful than other immigrants in earning enough to support their households, albeit with the help of their teenage children, fewer married immigrant Jewish women worked outside the home than all other married American women, immigrant or native. Immigrant families could not survive, however, on the father’s wages alone. Until they had children old enough to enter the labor market, women had to supplement their husbands’ wages while caring for their households. They did so by working at home, taking in piecework and especially cooking and cleaning for boarders. In fact, more immigrant Jewish households had boarders than any other immigrant group. A 1911 governmental study found that in New York City, for example, fifty-six percent of Russian Jewish households included boarders, as compared with seventeen percent of Italian households. Other Jewish women assisted their husbands in “mom and pop” stores—grocery stores, candy stores, cigar stores—which were generally located close to the family’s living quarters. Mothers ran back and forth between their customers in the store and the food cooking in their ovens, balancing their conflicting responsibilities. In most official documents, these women appear simply as housewives, but their labor was crucial to the family economy.

Almost all the women worked, of course, but their work patterns depended on their domestic obligations. Married women had full responsibility for managing the household, and the obligations of mothers were particularly heavy. Indeed, women and men alike assumed that wives would quickly develop skill in stretching their husband’s wages; their role as baleboostehs [efficient housewives]—shopping, cooking, and cleaning—complemented their husbands’ role as breadwinners.

Women Entrepreneurs

Some energetic immigrant Jewish women contributed to the family economy by becoming entrepreneurs. Female pushcart peddlers were a familiar sight in immigrant neighborhoods. As the sociologist Louis Wirth wrote in his 1928 book The Ghetto, “In accordance with the tradition of the Pale, where the women conducted the stores … women are among the most successful merchants of Maxwell Street [in Chicago]. They almost monopolize the fish, herring and poultry stalls” (236). Other women provided the initiative for their families’ economic success. One immigrant woman in New York City, for example, put her skills at bargaining and cooking to work in running a restaurant, whose profits were invested in real estate. In the early 1890s, Sarah Reznikoff, mother of the writer Charles Reznikoff, persuaded a garment manufacturer to give her the opportunity to show what fine ladies’ wrappers (loose dresses) she could sew at home. She soon persuaded him to hire as her partner her cousin Nathan, who later became her husband. Sarah made the decisions about hiring and firing workers. She convinced Nathan to become a foreman, in charge of eighty-six machines. When her husband’s fortunes failed years later, when their children were in school, she learned how to make hats and established a successful millinery business into which she brought her husband and brother. That business sustained the family while the children were growing up. Although she clearly had more business sense than her husband, she was content to recede into the background once she had laid the foundation for a family enterprise. No such reluctance to take center stage characterized Anna Levin, who immigrated to Columbus, Ohio, in 1914. She began by selling fish in a garage. Within a decade, her store, which now also sold poultry, fruits, and vegetables, was so successful that her husband gave up his carpentry work to join her in the business.

Gendered Expectations

Yet, varied household responsibilities filled most women’s daily routines, even those women involved in business. With fewer grandmothers and aunts available than was the case in the home country, and with mandated public education that kept older children at school, child care was burdensome. Keeping a crowded tenement flat clean and orderly in a grimy industrial city required much scrubbing. Laundry for the family had to be managed in cramped indoor conditions in cold-water flats. Limited family budgets forced housewives to spend hours circulating among stores and pushcarts looking for the best bargain. Literature written by the children of immigrant women praised their self-sacrifice as well as their capacity to cope with economic hardships, sometimes sentimentalizing the mothers in the process of acknowledging the difficulties of their lives. The critic Alfred Kazin typifies this view of the immigrant Jewish mother:

The kitchen gave a special character to our lives: my mother’s character. All my memories of that kitchen are dominated by the nearness of my mother sitting all day long at her sewing machine. … Year by year, as I began to take in her fantastic capacity for labor and her anxious zeal, I realized it was ourselves she kept stitched together. (66–67)

Many autobiographies and oral history interviews as well as fictional accounts have also commented on the central role played by mothers in the emotional life of the family.

Before marriage, most adolescent girls and young women worked to contribute to their families’ support. Like their fathers and brothers, they found jobs in the garment industries, especially the ladies’ garment trades. Because the wage scale and division of labor were determined by gender, immigrant daughters earned less than their brothers. Working full-time in garment shops, they earned no more than sixty percent of the average male wage. They worked in crowded and unsanitary conditions in both small workshops and larger factories. Their hopes for improving their economic circumstances lay in making an advantageous match, while their working brothers aspired to save enough to become petty entrepreneurs. Moreover, immigrant sons occupied a privileged place in the labor market in comparison with their sisters. In New York in 1905, for example, forty-seven percent of immigrant Jewish daughters were employed as semiskilled and unskilled laborers; only twenty-two percent of their brothers fell into those ranks. Conversely, more than forty-five percent of immigrant sons held white-collar positions, while less than twenty-seven percent of their sisters did. The roles and expectations of daughters within the family also differed substantially from those of their brothers. Even when they were working in the shops and contributing to the family’s income, girls were also expected to help their mothers with domestic chores.

The gendered expectations regarding work and the lower salaries that women earned made mothers particularly vulnerable when no male breadwinner could be counted upon. Women were more likely to be poor than were men. Widows with small children and few kin in America found it impossible to earn enough to feed and house their children. Wife desertion, sometimes referred to as the poor man’s divorce, became more frequent than in Europe. The Jewish Daily Forward, the most popular American Yiddish newspaper, printed the pictures of deserting husbands in a regular feature called the “Gallery of Missing Husbands.” The separation of families in the migration process and the poverty of immigrant workers spurred husbands to abandon their families. The personal and cultural divide between husbands and wives who had immigrated to America at different times occasionally became too wide to bridge.

Jewish philanthropic associations in the early 1900s spent about fifteen percent of their budgets assisting the families of deserted wives, and still more on the families of widows. Jewish communal leaders responded to these social problems not only through direct provision of charity, but also by establishing the National Desertion Bureau to locate recalcitrant husbands and orphanages to house poor children. No more than ten percent of residents of orphanages in the immigrant period were actually orphaned of both parents; rather their surviving parent was unable to care for them. The case of the family of Rose Schneiderman, the labor leader, was typical. After the death of her tailor husband from the flu, Rose’s pregnant mother was compelled temporarily to place her two sons, and briefly Rose, in New York’s Hebrew Orphan Asylum while she cared for her newborn infant.

Political Activities

Despite the differential they experienced in wages and social mobility because they were female, young immigrant women reveled in the freedom that wage-earning work conferred. As one proudly declared years later in an interview, “The best part was when I got a job for myself and was able to stand on my own feet” (Krause 296). Although immigrant daughters were expected to hand over most of their wages to their parents, and to accept this obligation to their families, they also developed a sense of autonomy, as they decided what small portion of their wages to keep back for their own needs. Like other urban working-class girls, they took advantage of the leisure-time activities that the city made available: dance halls, movies, amusement parks, cafes, and theater. Their sense of autonomy, reinforced by their participation in the labor force, extended to courtship and marriage. The custom of chaperonage disappeared in America, perhaps because the parents of young immigrants often remained behind in Europe, and young immigrant men and women considered it their right to choose their own spouses.

The years spent at work between the end of formal schooling and marriage contributed to the Americanization, and particularly the politicization, of immigrant daughters. Young Jewish women preferred to work in larger factories, where they came in contact with a more varied work force than in smaller shops and where they experienced a female community of their peers. Most importantly, they participated in the labor movement that became a powerful force within immigrant Jewish communities. In fact, their activity helped to shape the nascent Jewish labor movement, as young women activists, demonstrating in picket lines, repeatedly confronted the authorities.

Young immigrant women and immigrant daughters were reared with the sense that the world of politics was not reserved for men alone. Although the public religious sphere of the Jewish community had been closed to women in Eastern Europe, they participated in the public secular sphere of economic and political life. Radical socialist movements like the Bund were not as egalitarian as their rhetoric suggested, but they did recruit women as members. Unlike the women of some ethnic groups who were closely supervised by their men folk, immigrant Jewish women attended lectures and political meetings alone and often discussed the issues of the day. Gentile observers commented that Jewish working women were not concerned simply with their own tasks or skills. With confidence in their right to act politically, they demonstrated a great interest in labor conditions in general and in the left-wing political movements that addressed working-class problems. The immigrant Jewish community, particularly through the Yiddish press, validated their political involvement, providing support for female-led The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.kosher meat boycotts and rent strikes as well as for woman suffrage.

Although the male Jewish leaders in the nascent garment industry unions, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, did not accept women as their peers and discriminated against those who sought leadership roles, women in fact galvanized the Jewish labor movement. In the years immediately before World War I, the union movement achieved the stability that had eluded it until then, largely due to women worker militancy. The Uprising of the 20,000, the massive 1909 strike of women in the ladies’ garment trade, initiated a period of successful labor activism among Jewish workers. Women took their place on the picket lines and suffered arrest along with their male colleagues. Female activists such as Rose Schneiderman, Pauline Newman, Fannia Cohn, and Clara Lemlich Shavelson, along with others, devoted themselves to the cause of improving the economic conditions and the status of workers. They helped to introduce concern for workers’ education and recreation into the American labor movement. Jewish women probably contributed more than a quarter of the total increase in female members of all labor unions in the United States in the 1910s.

The political interest and sophistication of young immigrant Jewish working women continued even when they quit the garment workshops upon marriage. Within immigrant Jewish communities, older women with families engaged in political activity on the local level. From the 1890s through the 1930s, they spoke out and demonstrated on issues that directly affected their roles as domestic managers. When Margaret Sanger opened a birth control clinic in the heavily immigrant Jewish neighborhood of Brownsville, Brooklyn, Jewish housewives thronged to it, even though dispensing birth control information was then illegal. They organized boycotts in response to rising meat prices and conducted rent strikes to protest evictions and poor building maintenance. When New York state held elections on female suffrage in 1915 and 1917, they canvassed their neighbors, going from house to house to persuade male voters of their moral claim to enfranchisement. Because they had fewer institutional affiliations than men, women often have been omitted from scholarly examination of the Jewish community. Yet women found in their neighborhoods, in the streets and stoops where they spent their days, a sense of community that nourished their political activity.

Education

Although immigrant Jews kept their children in school longer than other ethnic groups, they invested more heavily in the education of their sons than their daughters. McClure Magazine’s 1903 story of Bessie, a department store girl with a brother in City College of New York, was not atypical. This family strategy made sense when women’s labor force participation was tied so closely to their marital status. But it also frustrated the dreams of many immigrant girls who had defined the freedom of America as the opportunity of studying as long as they liked.

As immigrant Jewish families prospered, they kept children of both sexes in school. The youngest in the family usually had the best chance of getting an education, irrespective of gender. Mary Antin, a precociously successful immigrant who wrote her autobiography at age thirty, recognized her privileged experience in comparison with her older sister’s. As she noted in The Promised Land, “I was led to the schoolroom, with its sunshine and its singing and the teacher’s cheery smile; while she was led to the workshop, with its foul air, care-lined faces, and the foreman’s stern command” (199). Even for the children of the most successful immigrants, however, social mobility was gendered. Sons went to college to become doctors or lawyers, while daughters attended normal school to become teachers. Of course, most immigrant sons did not even graduate from high school in the years before World War I; they became businessmen. Most immigrant daughters entered the world of white-collar work as saleswomen or commercial employees. They became schoolteachers in large numbers only in the interwar years, and only in a city like New York that allowed married women to keep on teaching. When they married, they became housewives, although the Depression compelled many to find employment, at least temporarily.

Because traditional Jewish culture valued education, and because their need to go to work thwarted their aspirations for attending high school and perhaps college, many immigrant Jewish women chose to supplement their meager formal education by taking advantage of free public evening classes and lectures organized by settlement houses, unions, and Yiddish cultural organizations. They saw in education the key to the freedom that America symbolized. As one woman who arrived in America as an adolescent in 1906 reminisced in her old age, “I told my parents, ‘I want to go to America. I want to learn, I want to see a life, and I want to go to school’” (Kramer and Masur 8). Sociological studies conducted both before World War I and in the 1920s documented the disproportionately large numbers of immigrant Jewish women in evening courses. In Philadelphia in 1925, for example, seventy percent of night school students were Jewish women. Many immigrant Jewish women, therefore, had the opportunity to acquire the secular education of which they had been deprived by a combination of economic conditions and governmental discrimination in their countries of origin. But many found that the straitened economic circumstances of their lives prevented them from achieving their dream. As one woman who arrived in America as an adolescent before World War I reflected years later, “I always wanted education. I never got it” (Weinberg 167).

Jewish Education & Religious Life

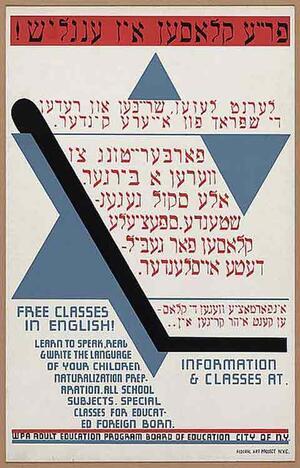

For the more than two million Jews from the Russian Empire, Romania, and Austria-Hungary who entered the United States between 1881 and 1924, mastery of the English language was critical to successfully becoming "American," as this Yiddish/English poster, part of a 1936–1941 Federal Art Project in New York City, demonstrates.

Institution: U.S. Library of Congress

Women had even fewer opportunities for Jewish education. The traditional exemption of women from formal Jewish study continued in the American immigrant community. Although only a quarter of immigrant Jewish children received any Jewish education, the situation of girls was particularly bleak. A 1904 study found that on the Lower East Side, there were 8,616 male students in traditional Jewish supplementary schools, but only 361 girls. In 1917, the situation had improved; one-third of the students enrolled in Jewish schools in New York City were female. But they received a more meager education than their brothers, often limited to Sunday school. A handful of girls did receive excellent Jewish education as well as training to be Hebrew teachers, as educational reformers like Samson Benderly found that they could introduce innovations more easily in schools for girls than in schools for boys. Only as Jewish communal leaders became aware that the Jewishness of the children of the immigrants could not be taken for granted, however, did they focus on the education of girls. Since middle-class Americans considered women to be more sensitive to religion than men and expected mothers to teach moral values to their children, Jews soon realized that the Jewish education of girls was critical to the transmission of Jewish identity to the younger generation.

The public space of the immigrant synagogue, as was the case in Eastern Europe, was reserved largely for men. We still know little about the religious practice of immigrant women in America. Women’s religious expression seems to have remained domestic. As so much Jewish observance is home-centered, immigrant housewives were responsible for the Jewish ambience of the entire household. Even in families whose traditional observance had lapsed, women prepared a special family dinner for Friday evening and made sure that appropriate foods were available on Jewish festivals.

Becoming American

Despite their political activity and secular knowledge, immigrant Jewish women were generally perceived by social reformers, both gentile and Jewish, to be obstacles to the successful Americanization of their families. Since they typically spent their days in their own households, they were presumed to be transmitters of Old World values. Recently, historians have revealed a far more complex role for women in the adaptation of immigrant Jews to American conditions.

Immigrants took the first steps toward becoming American when they put on ready-made American clothes. Working in garment factories and therefore familiar with the latest fashions, which changed more dramatically in ladies’ than in men’s wear, young women were often the first to outfit themselves in American styles and influenced the entire household’s clothing purchases. But dressing well did not mean spending a fortune. Jewish women became adept shoppers and learned how to put together a fancy outfit at little expense. As immigrants experienced upward social mobility, a wife’s clothing and jewelry signified the family’s success. Women purchased more than the family’s clothing. As domestic managers, they did most of the household shopping. As new consumer items became available and their husbands achieved economic success, Jewish women had numerous opportunities to select American merchandise, ranging from Uneeda Biscuits to parlor furniture, all widely advertised. Mass marketers used the Yiddish press to target Jewish housewives as consumers, perhaps aware of Jewish men’s relative economic success compared to other immigrant workers. Because of their long experience with the marketplace in Eastern Europe, and the cultural value of shrewd bargaining as a marker of the successful baleboosteh, immigrant Jewish women apparently became effective consumers. They introduced large numbers of American products into their homes, making them more American in the process.

American Jewish social reformers, the middle-class and highly acculturated descendants of earlier waves of immigration, recognized the potential of immigrant women as agents of assimilation, but felt that they needed to be directed to exert appropriate influence on their families. The social reformers impressed on immigrant mothers the values of cleanliness, social order, and class deference in order to turn them into good Americans. The eagerness with which Jewish social reformers embraced this task resulted from their realization that gentile Americans were unlikely to distinguish between different types of Jews. The new immigrants were so numerous and visible in their Yiddish-speaking ghettos, so conspicuous in their radical politics, that they threatened to displace the prosperous, respectable German Jewish banker or merchant as the representative Jew in the popular imagination. In short, they worried that immigrant foreignness would provoke antisemitism. For American Jewish social reformers, teaching appropriate gender roles to the immigrants from Eastern Europe involved curtailing what reformers considered the “deviant” behavior of immigrant women by making them Americans on the middle-class model.

Jewish Reputation

Social reformers particularly feared disreputable behavior on the part of women as likely to contaminate the reputation of all Jews. This led Jewish women reformers to focus on the disturbing issue of Jewish prostitutes and, to a lesser extent, Jewish pimps. Although relatively few Jewish women were involved in prostitution, the fact that 17 percent of women arrested for prostitution in Manhattan between 1913 and 1930 were Jewish prompted serious concern. Furthermore, Jewish prostitutes and pimps were a stock-in-trade of purveyors of antisemitism. Similarly, reformers recognized the presence of unwed mothers among immigrants as a sign of family breakdown. When the National Council of Jewish Women addressed these issues by stationing a dock worker at ports of entry to protect immigrant Jewish women and girls traveling alone from procurers, or by establishing the Lakeville Home for Unwed Mothers, they sought to ameliorate the situation of unfortunate women. Male-dominated Jewish organizations seemed to be motivated as much by concern for the prevention of antisemitism as by the victimization of Jewish women. For all Jewish social welfare providers, evidence of women’s deviant behavior shook one of the foundation stones of the Jewish claim to moral superiority, the reputation of the Jewish family for unblemished purity.

Jewish social reformers shared the prejudices of their class. They sought not only to train women for their domestic roles as respectable wives and mothers. Because they were dealing with their social inferiors, they also aimed to teach their clients that workers should respect their “betters” in the middle class and that women should defer to men. The Clara De Hirsch Home for Working Girls, which was at the same time a boarding house and a vocational school, limited its training to marketable skills that were also of use to women as homemakers, such as hand and machine sewing, dressmaking and millinery, even though it recognized that its working-class clientele would have to support themselves through wage labor and would benefit economically by learning diverse skills. The girls at the school resoundingly rejected the home’s program in domestic service. Unlike the directors of the institution, they did not presume that their class status was fixed; they thought America promised middle-class comfort to all who worked hard. They also shared a Jewish disdain for domestic service, which was culturally devalued by Jewish migrants from both Central and Eastern Europe. The Hebrew Orphan Asylum went even further than the Clara de Hirsch Home. The asylum supervised discharged adolescent girls and discouraged them from seeking employment, such as working as waitresses or salesgirls in department stores, that might lead to immorality. Although the Educational Alliance, the largest Jewish settlement house in New York City, could not control its clientele as did the residential facilities, it devised programs to inculcate appropriately American behavior in youth. The alliance provided different recreational programs for boys and girls. Boys were encouraged to join competitive athletic teams whose success in meets with other settlement houses might refute the stereotype of Jewish males as weak and cowardly. A similar program did not exist for girls. Instead, they were taught housekeeping and cooking so that they might, in the words of the institution’s 1902 annual report, “cultivate a taste for those domestic virtues that tend to make a home-life happier and brighter” (Educational Alliance 21).

The Influential Position of Jewish Wives & Mothers

Immigrant Jewish writers of Yiddish-language advice manuals also appear to have recognized the influence of wives and mothers on the members of their families. Their books addressed a primarily female audience and focused on issues assumed to fall within women’s domain, such as child rearing, fashion, table manners, and birth control. As Chaim Malitz noted in his 1918 book entitled Di Heym un di Froy [The home and the woman], “Take away the mother from the home, and there remains no home” (41). Ironically, male purveyors of advice literature singled women out for attention, because they felt women had not yet succeeded in their task as agents of Americanization. Yet the authors acknowledged that women were the family members most likely to introduce middle-class standards of behavior and taste into their homes. Women could transform their husbands and children into Americans.

Oral history interviews and memoirs suggest that immigrant women, in fact, used their domestic position to mediate between home life and the public world of school, work, and recreation. Daughters, in particular, have commented upon how their mothers supported their aspirations and desires for independence and education. Women’s fiction, too, often depicts immigrant mothers as wielding their influence, not always successfully, to mitigate a father’s rigid religious traditionalism that would deny their daughters freedom to choose a spouse or to go off to study. Some historians and cultural critics lament what they perceive as a transfer of power within the immigrant Jewish household from the father to the mother, but they share with those who write positively about the immigrant mother a recognition of her centrality in her home.

Women who immigrated to America from Eastern Europe discovered their lives stamped by the economic, social, and cultural impact of their migration. Although the cultural tradition the immigrants brought with them permitted women more autonomy than was the case among other immigrant groups, economic circumstances constricted Jewish women living on the Lower East Side. Moreover, Americans’ understanding of success in America limited women’s aspirations. Americans assumed that if a married woman engaged in paid work, she was not appropriately feminine, and her husband was a failure. This meant that volunteer social work became the main outlet for the creative energies of Eastern European immigrant Jewish women who enjoyed the luxury of leisure time and sought meaningful work. These Eastern European immigrant women followed a similar path of an earlier generation of women who founded Jewish women’s organizations like Hadassah and the National Council of Jewish Women. Eastern European immigrant women also set up a host of local organizations, ranging from day nurseries to maternity hospitals to old-age homes. Hopes that immigrant women had harbored for themselves were often transferred to the younger generation. As Sarah Reznikoff concluded in her memoir, “We are a lost generation. … It is for our children to do what they can” (99).

Primary Sources

Antin, Mary. The Promised Land. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1912 (Reprint, 1969).

Educational Alliance. Annual Report of 1902.

Gorenstein, Lillian. “A Memoir of the Great War, 1914–1924 (In Memory of my beloved brother, Morris).” YIVO Annual 20 (1991): 125–183.

Kramer, Sydelle and Jenny Masur, eds. Jewish Grandmothers. Boston: Beacon Press, 1976.

Marcus, Jacob Rader, ed. The American Jewish Woman: A Documentary History. New York: KTAV Publishing House, 1981.

Reznikoff, Sarah. “Early History of a Seamstress.” In Family Chronicle, edited by Charles Reznikoff. London: Norton Bailey, 1969.

Schneiderman, Rose, with Lucy Goldthwaite. All for One. New York: P.S. Eriksson, 1967.

Secondary Sources—Books

Baum, Charlotte, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel. The Jewish Woman in America. New York: Dial Press, 1976.

Bristow, Edward. Prostitution and Prejudice: The Jewish Fight Against White Slavery, 1870–1939. New York: Schocken Books, 1983.

Ewen, Elizabeth. Immigrant Women in the Land of Dollars: Life and Culture on the Lower East Side, 1890–1925. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1985.

Friedman, Reena Sigman. These Are Our Children: Jewish Orphanages in the United States, 1880–1925. Waltham, MA: University Press of New England [for] Brandeis University Press, 1994.

Glanz, Rudolf. The Jewish Woman in America: Two Female Immigrant Generations, 1820–1929. Vol. 1, The Eastern European Jewish Woman. New York: KTAV and National Council of Jewish Women, 1976.

Glenn, Susan A. Daughters of the Shtetl: Life and Labor in the Immigrant Generation. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Heinze, Andrew. Adapting to Abundance: Jewish Immigrants, Mass Consumption and the Search for American Identity. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Hyman, Paula E. Gender and Assimilation in Modern Jewish History: The Role and Representation of Women. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995.

Joselit, Jenna Weissman. The Wonders of America. New York: Hill and Wang, 1995.

Kazin, Alfred. A Walker in the City. Boston: Harcourt, 1951.

Kessner, Thomas. The Golden Door: Italian and Jewish Immigrant Mobility in New York City, 1880–1915. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Orleck, Annelise. Common Sense and a Little Fire. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Raphael, Marc Lee. Jews and Judaism in a Midwestern Community: Columbus, Ohio, 1840–1975. Columbus, OH: Ohio Historical Society, 1979.

Smith, Judith E. Family Connections: A History of Italian and Jewish Immigrant Lives in Providence, Rhode Island, 1900–1940. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985.

Weinberg, Sydney Stahl. The World of Our Mothers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

Secondary Sources—Articles

Hyman, Paula E. “Gender and the Immigrant Jewish Experience in the United States.” In Jewish Women in Historical Experience, edited by Judith R. Baskin (1991), and “Immigrant Women and Consumer Protest: The New York Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902.” American Jewish History 70, no. 1 (1980): 91–105.

Kessler-Harris, Alice. “Organizing the Unorganizable: Three Jewish Women and Their Union.” In Class, Sex, and the Woman Worker, edited by Milton Cantor and Bruce Laurie. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977.

Krause, Corinne Azen. “Urbanization Without Breakdown: Italian, Jewish, and Slavic Immigrant Women in Pittsburgh.” Journal of Urban History 4, no. 3 (1978): 291–306.

Kuznets, Simon. “Immigration of Russian Jews to the U.S.: Background and Structure.” Perspectives in American History 9 (1975): 35–124.

Sinkoff, Nancy B. “Educating for ‘Proper’ Jewish Womanhood: A Case Study in Domesticity and Vocational Training, 1897–1926.” American Jewish History 77, no. 4 (1988), 572–599.