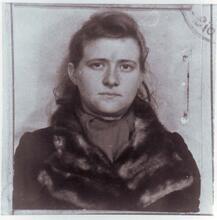

Sophia Dubnow-Erlich

Sophia Dubnow-Erlich studied at Bestuzhev in St. Petersburg, where her first published poem, “Haman and His Demise,” caused a scandal in 1904 for its satiric portrayal of the czar’s minister of the interior. After finishing her education, Dubnow-Erlich became an active member of both the Social Democratic Labor Party and the Jewish Labor Party and wrote for Bund journals before fleeing Vilna for Warsaw in 1918. Dubnow-Erlich emigrated to America in 1942; she lost both her father and her husband in the Holocaust. She remained politically active in the United States, fighting for civil rights and protesting the Vietnam War, and wrote poetry, essays, translations, political histories, a biography of her father, and an autobiography, Bread and Matzo.

Although the Jewish academic community has typically cast her as either the daughter of the historian Simon Dubnow or the wife of the Bundist leader Henryk Erlich, Sophia Dubnow-Erlich was in fact a poet, political activist, critic, translator, and memoirist in her own right. Her literary corpus tells the remarkable story of one Eastern European Jewish woman’s entry into two very disparate spheres of activity. Over a lifetime spanning 101 years (forty-four years spent in the United States), Dubnow-Erlich engaged in Jewish socialist party politics, on the one hand, and Russian Silver Age poetry, on the other.

Early Life

Born on March 9, 1885, in Mstislavl, Belarus, Sophia Dubnow-Erlich (Sofiia Dubnova-Erlikh) was the eldest child of Simon and Ida (Friedlin) Dubnow. At age five, she and her parents, along with siblings Olga and Yakov, moved to Odessa. Her father began to instruct her according to John Stuart Mill’s educational system until age fourteen, when she entered a gymnasium. Upon graduation in 1902, she studied at the Bestuzhev Higher Courses in St. Petersburg, a four-year degree program equivalent to that of the university, offered to women with parental permission and the annual tuition of fifty rubles.

Simultaneously, she began her foray into both the literary and political worlds in 1904, when her first poem, “Haman and His Demise,” appeared in the Russian Jewish weekly Budushchnost’ [Future]. Her satire of the czar’s minister of interior, Plehve, was immediately confiscated by the censors, while her proud father wrote the Zionist leader Ahad Ha-Am: “Our daughter is the hero of the day.” That same year, university officials expelled her from her courses for participating in a student protest. Undeterred, she entered the history-philology department of St. Petersburg University in 1905 and later studied comparative religion and the history of world literature at the Sorbonne (1910–1911).

Political Participation

Meanwhile, her family had moved to Vilna, the hotbed of Jewish politics in the Russian Empire, where she became an active member of the Social Democratic Labor Party and the Jewish Labor Party, and an antimilitarist propagandist. As she explained in her 792-page Russian-language memoir, “The anxiety of our generation was destined to become intertwined with the anxiety of our era.” She sealed that fate in 1911 by marrying Henryk Erlich (1883–1941), a prominent leader of the leftist Bund in Poland.

In deed and in printed word, the couple worked to promote the ideals of Jewish cultural autonomy and socialist internationalism. Dubnow-Erlich, for instance, wrote for various Bund journals, including Nashe Slovo [Our word] and Evreiskie Vesti [Jewish news], during World War I and the Russian Revolution. By 1918, the political situation drove the Dubnow-Erlich and her husband to relocate to Warsaw, where they remained for over twenty years with their sons, Alexander and Victor. When Warsaw fell to the Nazis in 1939, Henryk Erlich was arrested by Soviet authorities, and Dubnow-Erlich moved her family to Vilna, where they lived until 1941. When she reached the United States in 1942, she learned of her husband’s death and her father’s murder by the Nazis. Dubnow-Erlich remained politically active in her new land as well, advocating for civil rights and protesting the Vietnam War.

Later Life

Despite the early sensation over her poetic debut, Dubnow-Erlich’s writing career soared well into her nineties. She contributed over fifty poems, essays, and translations to Russian and Yiddish-language journals and newspapers on her dual interests in the high arts and politics, as well as producing three volumes of symbolist poetry, several histories on topics relating to the Bund, and a biography of her father. A sampling of her writings shed light on the experiences of women in general and mothers in particular.

Sophia Dubnow-Erlich died on May 4, 1986, in New York. Her fascinating life and extensive literary oeuvre of varied genre, most of which has not yet been translated into English, deserves the full attention of students of history and literature alike. The tapestry of her life is woven into the very fabric of Eastern European Jewish history of the twentieth century.

Selected Works

Biografye un Shriftn. Leyvik Hodes (Bund leader in Vilna in Yiddish). Edited by Sofie Dubnov-Erlikh (1962).

Di Geshikhte fun ‘Bund’ (collective history of the Bund in Yiddish). 5 vols. Edited with Jacob S. Hertz, Gregor Aronson, et al. (1960–1981).

Garber-bund un Bershter-bund Bletlekh fun der Yidisher Arbeyter-bavegung. Translated from the Russian by Khaim Shmuel Kazdan and Leyvik Hodes (history of two intercity Bundist unions in Eastern Europe in Yiddish) (1937).

Khmurner-bukh (on Josef Leszczynski and the Bund in Poland in Yiddish). Edited with Leon Oler [Ohler] (1958).

The Life and Work of S.M. Dubnov. Translated by Judith Vowles. Edited by Jeffrey Shandler (1991; original in Russian, 1950).

Mat’ (poetry collection on motherhood in Russian) (1918; reprint 1969).

Osenniaia Svirel’: Stikhi (poetry collection in Russian) (1911).

Stikhi Raznykh Let (poetry collection in Russian) (1973).

Khleb i Matsa (Bread and matza). 1994. Dubnova-Erlikh, Sofii︠a︡., and Shaw, Alan. Bread and Matzoth. Tenafly, N.J.: Hermitage, 2005.

Aaronson, G. Ia. “Dubnov-Erlikh, Sofie (9 March 1885–).” Leksikon fun der Nayer Yidisher Literatur 1 (1958): 466–467.

Dubnow-Erlich, Sophie. Archives. YIVO, NYC, and Professor Kristi Groberg, University of Minnesota, Duluth.

Dubnova-Erlikh, Sofii︠a︡, and Alan Shaw. Bread and Matzoth. Tenafly, N.J.: Hermitage, 2005.

EJ 6:844–845, s.v. “Ehrlich, Henryk.”

Erlich, Victor. Child of a Turbulent Century. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2006.

Groberg, Kristi A. “Dubnov and Dubnova: Intellectual Rapport Between Father and Daughter.” In Simon Dubnov 50th Yortsayt Volume, edited by Avraham Greenberg and Kristi Groberg (1994).

Groberg, Kristi A. “Dubnova, Sofiia Semenovna.” Dictionary of Russian Women Writers (1994).

Groberg, Kristi A. “Sophie Dubnov-Erlich.” In European Immigrant Women in the United States: A Biographical Dictionary, edited by J.B. Litoff (1994).

Obituary. NYTimes, May 6, 1986.