Medieval Spain

Written histories of Jews in medieval Spain rarely include women, so one must seek alternate sources. Marital status was the frequent topic of rabbinic responsa. The rabbis of Spin never took a united stance on polygyny, and some rabbis permitted concubines. Some Jewish women had their own source of income, functioning as merchants and moneylenders. Inheritance laws were problematic for Jewish women–disputes were settled in both Jewish and non-Jewish courts. The forced conversions of 1391 changed the face of Spanish Jewry, although conversas and Jewish women found ways to make contact. The Edict of Expulsion issued in 1492 sealed the fate of the Jewish community; while Jews could no longer practice Judaism in their homeland, the Spanish Jewish way of life continued in the Sephardi Diaspora.

Written histories of the Jews in Spain have rarely included women. The two major historical works in the field, The Jews of Moslem Spain (2 vols.) by Eliyahu Ashtor (1973) and A History of the Jews of Christian Spain (2 vols.) by Yitzhak Baer (1961), offer relatively little information about women. Consequently, one must seek alternate sources, which is by no means an easy task. When dealing with Jewish women in Spain, the available sources range from poems, letters, and rabbinic literature to Latinate wills, court records and Inquisition documents. During the earlier Islamic period (711–1060), it is especially difficult to find relevant sources.

Women Writing in Medieval Spain

Because the general level of education for girls was rather limited in medieval Spain, it is rare to find women’s writings. The exceptions to the rule include the poet Qasmuna, who was taught by her father to write rhymed verses that would complement his own. Qasmuna was apparently reared in an educated family, for her father was a poet, and as is the case in many communities, girls in the upper class or educated elite often received private tutoring at home or would audit their male siblings’ lessons. In the case of Qasmuna, because of a reference in one of her few extant poems in Arabic, there is an ongoing scholarly debate concerning her identity; there are those who are convinced that she was none other than the daughter of Shmuel ha-Nagid (993–1055/56), the eleventh-century poet-warrior of Granada, who was known to have had a daughter. If so, she would have been exposed to a truly elitist environment. The wife of the Nagid, as well as the daughters of the poet Judah Halevi (before 1075–1141), were also know to have been educated women.

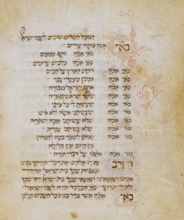

The other outstanding example of an erudite woman from these literary circles was the wife of Dunash ben Labrat, one of the tenth-century Hebrew poets of the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry. This unnamed woman and her poem have a fascinating history. A fragment discovered in the Cairo Place for storing books or ritual objects which have become unusable.Genizah was at first incorrectly identified as having been composed by ben Labrat. Years later, additional fragments were discovered and identified as belonging to the first segment; once properly compiled, scholars were stunned to learn that in effect there were two letter-poems that complemented each other. One was written by ben Labrat, while the other was composed by his wife. The eminent scholar of medieval Hebrew literature, Prof. Ezra Fleisher of the Hebrew University, declared that this woman was probably the first female Hebrew poet in history. Not only is her style sophisticated and flowing, but it is as impressive as that of her husband. In his poem, ben Labrat refers to her as being highly educated, and again, the ability to write poetry in Hebrew on such a high level attests to an unusual education for any Jewish woman.

Other examples of writings by literate women from Spain have been collected by Prof. Joel Kraemer of the University of Chicago, who identified letters in the Cairo Genizah that were dated to a much later period than most of the findings; these letters were written by “Spanish Ladies,” as he refers to them. Most of these women were exiles who left Iberia in 1492, and wrote letters to members of their family in other locales. Kraemer even found examples of women who, after settling in Arabic-speaking countries such as Egypt, learned to write in Judeo-Arabic; nevertheless, the strong influence of their native tongue, Spanish, can be discerned in their writing style. Family ties and values emerge in this correspondence, as does the fact that some of the women cared for their brothers, husbands and families. Many of the letters reveal an unexpected social and legal independence on the part of the women, perhaps because they were uprooted from their homes; most of the women do not seem to be tied to a male family member or limited in their activities solely to the domestic realm.

This image stands out in contrast to the one projected in traditional literature, in which the Spanish men, be they Muslim, Christian or Jewish, were anxious to keep their women under tight control. Visitors to the Iberian Peninsula reported that unmarried maidens never ventured into the street and that, in general, women were kept out of the public eye. This attitude is considered to have been the result of the influence of Islamic treatment of women and of the Talmudic precepts and traditions that advocated restricting women to the home domain; however, it was often more of an aspiration than the reality.

The Issue of Polygyny

In order to comprehend the rabbinic stance, one needs to examine the literature, especially the rabbinic Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsa was whereby the Jewish court was asked a legal question and an eminent rabbi would provide his learned reply. As will be shown, this type of material can uncover interesting cases of legal entanglements and reveal the way in which the rabbinic world dealt with problems that involved women. Nevertheless, it is obvious that women’s voices are rarely, if ever, heard in these documents, which are also, unfortunately, anonymous and undated. As will be illustrated, rabbinic responsa can provide one important means, albeit somewhat limited, of studying women’s lives in medieval Spain.

Marital status and related problems often are a frequent topic of rabbinic responsa. As in Genizah society (the Jewish Society of the Mediterranean Basin from 950–1250, as reflected in the documents of the Cairo Genizah), there seems to have been a fair amount of mobility, especially on the part of the men and particularly those engaged in commerce. In fact, the absence of a husband, which was often prolonged, proved to be a main catalyst for requests by women for divorce. As in Genizah society, the option of polygyny was available for the men and its prevalence is usually attributed to the influence of Islamic society. Since only Ashkenazi Jewry accepted the ban on polygyny enacted by R. Gershom (960–1028), the Iberian Jew who could afford a second wife could ostensibly marry one. During the rule of Islam, there was no opposition by the rulers to this practice. During Christian rule (1060–1492), although it was technically forbidden, permission could be obtained from the king, albeit for a considerable fee; this permission was needed in order to guarantee that the offspring of the union would have inheritance rights.

The rabbis of Spain never took a united stance, either in Castile or in Aragon, although they tended not to favor bigamy. Some women had a monogamy clause in their marriage contract which stipulated that the husband could not take a second wife or a maidservant if his wife objected. If he ignored her objection, he was obligated to grant her a divorce and to pay the divorce payment stipulated in the marriage contract. Otherwise, he would be ostracized by the community until he complied. On the other hand, a woman without this clause in her contract would be unprotected. During Muslim rule, this appears to have been a cross-class phenomenon, and many examples appear in eleventh- and twelfth-century rabbinic responsa; needless to say, the wealthy would naturally be more apt to engage in the practice of polygyny, which they could afford.

Adultery, Concubines, & Prostitutes

Sexual liaisons existed between Jewish women and non-Jewish men. One military leader, Sa’id ibn Djudi, was reported to have been slain in the home of his Jewish mistress. In 1320, a case of sexual relations of this sort came to the attention of a Christian ruler who gave the honor of judging the woman to the Jewish court: two rabbis recommended cutting off her nose. A wealthy widow, Doña Vellida of Trujillo, was arrested on three counts between 1481 and 1490; all three concerned adultery with Christian men.

Mobility on the part of the husband due to business demands often led to straying from his wife’s bed; men took a concubine or another wife while away from home. R. Isaac Alfasi (1013–1103) advised husbands to earn a living at home rather than take a second wife. On the other hand, the eminent R. Hasdai Crescas (d. 1412), head of Aragonese Jewry, had two wives, setting a dangerous example for the community.

Some rabbis, including R. Yonah of Aragon (13th c.) permitted concubines. In thirteenth-century Castile, there were Jewish men with both Muslim and Gentile concubines and Christians with Jewish and Muslim concubines. Many female Muslim servants became mistresses of their masters and sometimes poor Jewish women would establish relationships with wealthy men. The community of Toledo attempted to ban the practice of taking Muslim concubines in 1281, but to no avail. Nahmanides himself (1199–1270) advocated allegiance to one woman at a time and preferred a liaison by a Jewish man with a concubine to his having relations with various women, among whom might be prostitutes.

Jewish men went to prostitutes of all three faiths in Spain. There was even a Jewish brothel in existence in thirteenth-century Saragossa and a discussion as to whether seeking the services of a Jewish versus non-Jewish whore was recommended. A fifteenth-century discussion included the argument that Jewish prostitutes prevented men from sinning with married women and was thus preferable to adultery. R. Isaac Arama of Castile (c. 1420–1494) was opposed to frequenting prostitutes and reported that one community, nevertheless, provided stipends for prostitutes. Again, these practices were, on the whole, more prevalent among males of the upper class.

The Danger of Conversion

These findings reflect the influence of Islam on Jewish society as well as various types of interaction between the different religious groups in Spain. One fascinating account from the Cairo Genizah reveals details of the life of a woman who converted to Judaism in the second half of the eleventh century. This story, like that of the wife of ben Labrat, also came to light in fragments, but the final result is illuminating. This nameless woman came from an eminent Christian family in Provence and married David Narboni after converting. Her family was furious with her and proceeded to pursue her for years. The couple sought refuge in a small village near Burgos, and after six years comprised a family of five with three children. Unfortunately the village they chose experienced a pogrom in which Narboni was killed and the two older children were taken captive. At this point, the convert asked a scribe from Andalusia to draft a petition appealing to Jews of various communities to help her redeem her children.

The widow eventually remarried and attempted to rebuild her life, but her former family still pursued her, eventually locating her in the town of Najara. As a result, she was imprisoned, presumably because it was forbidden for a Christian woman to convert and marry a Jew; preparations were made for her execution. However, a wealthy Jew, possibly a relative of her first husband, provided a sum with which to bribe the clergymen in charge of the prisoner; at the last moment, in the dead of night, the convert was whisked away to freedom. Once again, she found herself in need of funds, this time in order to pay the debt of freedom, and once again, she approached the same scribe to prepare another letter for her to present to various Jewish communities. In the end, this Jewish woman fled Spain, realizing that, as a convert from Christianity to Judaism life was simply too dangerous for her under Christian rule; she arrived in Cairo along with her letters, which eventually found their way into the Cairo Genizah. Here one sees how the community rallied around her in support, for once she had converted, she was accepted by the Jewish communal institutions. At the same time, the trials and tribulations she faced reflect the dangers of living in Spain during periods of unrest and religious tensions.

Economic Activities & Widowhood

The inner tensions in the community as well as the upheavals faced by Spanish Jewry clearly affected women’s lives; reflections of such developments can also be found in responsa literature. One outstanding example deals with the attitude towards a woman who has been twice widowed. The term of reference used is “killer wife,” and a fear of allowing such a woman to remarry can be discerned both on the popular as well as on the scholarly level. Moses ben Maimon (Rambam), b. Spain, 1138Maimonides was the rationalist was avidly against forcing a man who had married a “killer woman” to divorce her; Nahmanides was not necessarily against such a sanction. In terms of Spanish Jewish history, proclivities in this matter changed. After the plague of 1348–1349 and the pogroms of 1391, which will soon be discussed in more detail, there was more leniency when making rulings in this regard. Rabbi Crescas declared that this type of widowhood clearly did not qualify the woman as a “killer.” On the other hand, the spread of The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah was also adversely affected the way in which widows were perceived. In mystical circles, women were never encouraged to re-marry due to the belief that the husband’s soul was awaiting that of his wife. Although Maimonides attempted to counter these trends, mysticism held its own on the popular level and many rabbis ruled that a woman twice widowed could not remarry.

While the aforementioned tale of the convert makes it clear that she did not have her own source of income, there were Jewish women in Spain who did. Women of limited means were sometimes supported by the community or might have jobs such as in the ritual bath or bathing the dead for the burial society. Some were wet-nurses and midwives; the latter, if successful, could even be found in the courts. There is evidence of Jewish women practicing medicine, which could result in malpractice suits on one hand or in authorizations from the king, on the other. Many working women were engaged in the traditional crafts of spinning, needlepoint, and weaving. Women can be found going to market, ostensibly to sell their wares, be they crafts or produce, since there were Jews in Spain who owned land, particularly vineyards. In fourteenth-century Navarre, there are records of women selling chicken, eggs and wine, as did the non-Jewish peasants. Women of the middle class were involved in the economy as merchants as well as moneylenders, especially when husbands were out of town or when they passed away and the widow needed to support herself and her children. Many women were able to make productive use of their dowries, and one can find details concerning them in marriage contracts, in wills and in litigations. Sometimes the king might even become involved in protecting dowry rights. One wealthy woman from Pamplona was so well established that the king granted her special privileges during the second half of the fourteenth century. This woman, Doña Encave, even provided the court with merchandise such as embroidered purses, silk, silver and jewels.

Once property was acquired, a woman could buy or sell, exchange or donate it as she pleased. Needless to say, the widow was the woman with the greatest degree of freedom regarding use of her dowry or other property or resources. In twelfth-century Perpignan, for example, it was rare for widows, both Jewish and Christian, to remarry; remarriage would mean losing custody of one’s children as well as of financial guardianship. Many women in this community, whether married or widowed, engaged in moneylending together with their husbands, guardians or other family members, as well as on their own. Most of them dealt with smaller amounts than did their male counterparts, but they were engaged in a respectable and profitable profession and handled the same kinds of business as did the men. Wives tended to be more active in this field when there was financial stress in the family and no male relatives to help out, or in cases of bankruptcy or, on the other hand, if there was a booming business that required their participation.

The wealthier widows dealt in larger amounts, as would be expected. One widow, Regina, was also named as guardian for her sons and was such a successful businesswoman that she had Christian investors supporting her in the 1280s. She was one of the twenty leading moneylenders in Perpignan. Information concerning these activities can be found in Latin notarial registers; this prosperous community was part and parcel of the developing Mediterranean economy and the Jews were supplying credit to members of this town and of those nearby. The Jews took care to register any important financial transactions, and thus loans, investments, lawsuits, and wills were recorded by notaries. When a widow was appointed as guardian, she was usually assigned co-guardians as well; these were usually individuals upon whom she could rely in case of distress. Another Regina, the widow of Bonsenyor Jacob, proved herself efficient as a guardian, but had four men on her panel of guardians, including the eminent Hebrew poet, Yedayah ben Abraham Bedersi (1270–1340). Her appointment was, nonetheless, far more than symbolic; although she turned to others in moments of need, she succeeded in securing the prosperity of the estate of her wards. While rabbis like Solomon ben Abraham Adret of Barcelona (the Rashba, 1235–c. 1310) ruled that women were incapable of conducting their own affairs, women were actually encouraged by their communities by virtue of the fact that they were named as their children’s guardians. Here is an example of the gap between theory and practice which exemplifies how women in some communities in Spain attained a surprising degree of economic independence.

Latin documents also reveal that women sometimes had their wills recorded by Christian notaries; no doubt this was true only of the affluent. Some of the heirs included in their wills were God, a sister who was to commission the writing of a Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah was scroll in 1338, and dowries for unmarried girls. A strong philanthropic element emerges in most of these wills, some of which were quite simple whereas others were rather complex. One woman left the synagogue her bed, together with her bedclothes and furnishings; many left money and property to other women, mostly relatives and friends. One unusual will from 1306 belonging to Astruga declares that her husband can have her money as long as he remains unmarried and supports her mother in his house. If, however, he remarried or did not remain chaste, the money would pass to her mother. She also contributed to the synagogue, and left her children clothing and other goods.

As has been seen, women with means were active with regard to their property. Often they would make sure to have their closest male relatives present as witnesses for transactions in order to prevent any contestation at a later date. In 1220, a woman who negotiated the sale of various plots took care to have the notary mention that her brother and step-son, her potential heirs, were present at the transaction. Another woman sold her husband’s plot with the consent of her father-in-law while her husband was away. She was determined to pay her husband’s debts but knew that technically she had no right to do so in his lifetime; the explicit consent of the father-in-law which she had procured would serve to protect her. Among these Latin documents, there were Jewish men from Catalan who signed in Hebrew, but no women; illiterates used a sign in tandem with a witness’s Hebrew signature, but illiteracy did not preclude either men or women from engaging in business.

Court Appearances & Settling Disputes

Women appear in both Jewish and non-Jewish courts. One Bonadona attempted to claim her marriage contract in 1329 while her husband was still alive because of her fear that he was about to declare bankruptcy; she appeared with both Jewish and Christian legal representatives. Her contention was that by having financial control of her dotal estate, her assets could not be claimed by her husband. The rabbis did not approve of this demand, which had no legal precedent. Husbands often managed their wives’ dowries during the duration of their marriage and could obviously abuse this privilege as well.

Another woman filed a complaint with R. Adret stating that her sister-in-law had no right to take control of two seats in the synagogue and that the Jewish court had not dealt with this problem to her satisfaction. Her contention was that while there was a local ordinance regarding ownership of seats, this ordinance was applicable only to the males of the community. Her rationale as that the women were not aware of these ordinances because such decrees were part and parcel of the public domain from which the women were excluded; in short, women were at home and incommunicado. Surprisingly enough, the rabbi rejected this contention and stated that under certain circumstances, women could not stay at home. For example, women with assets had to venture outside their domicile in order to take oaths regarding their tax assessments; otherwise a special petition had to be made to the king for the right to take oaths at home.

At the same time, it is clear that women were attending and being seen at the synagogue as well as making donations for its upkeep. It is precisely in the synagogue itself that women were able to address the community if they had a grievance that was not being properly taken care of by the community. This practice, whereby the prayers were interrupted, was an option for any member of the community, although women would use it only under dire circumstances. For example, a widow in Catalonia in 1261 claimed that the guardians of her marriage contract were not behaving appropriately. An investigation by the Jewish court determined that this was indeed the case, and that she had not received appropriate funds. The court chose a plot of land to sell in order to obtain the funds that were owed her; she, in turn, chose strategic plots to purchase in order to protect her own and her daughter’s interests. In the course of this struggle, this widow had no compunctions about appearing twice before the court on her own; the claimant had come to the conclusion that no one else could be trusted to represent her own interests. There are many cases of women appearing with guardians or appointing agents for sales of land or loan collection, but if truth be told, there were also men who appointed agents or representatives in court.

Inheritance laws were problematic for women. Jewish law stood out in contrast to that of the other co-existing religions: Christian widows automatically inherit half of their husband’s estate and Muslim women inherit a portion, while their daughters receive half of their son’s share. Rabbis in fourteenth-century Toledo, for example, did not agree upon which law to follow. Sometimes men bypassed the Jewish law because it left the widow no more than her marriage contract; by recording wills with Christian notaries, they could leave whatever they desired to their wives and often did precisely that.

At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the rabbis of Toledo passed an ordinance that concerned women and bequeathing property which was accepted by many of the other communities. If a wife pre-deceased her husband, the widower would inherit half of her property and her children would inherit the other half. The emphasis here is on her children, in order to prevent children born of another wife from inheriting. If she had no children, her family received that half; this appears to reflect the influence of Christian inheritance practices.

After 1391: Interactions between Conversas & Jewish Women

Perhaps the greatest effect that Christian society had on Jewish society was as a result of the forced conversions in 1391. Tens of thousands of Jews were forced to choose to convert or to die. The face of Spanish Jewry was completely changed due to the loss of those choosing martyrdom, the loss of property as the result of pillaging and the fact that so many former brethren, including friends, family members, rabbis and others, became Catholics overnight. Since the fate of the conversas, or women who converted, and their offspring is discussed elsewhere, attention will be paid here to the way in which this development affected the lives of women who remained Jewish.

In the Edict of Expulsion, the Jews were blamed for teaching the conversos Jewish rites and laws and for setting an example and providing inspiration for the judaizer or crypto-Jew. Interestingly enough, the image that emerges on the basis of testimonies, in particular confessions by judaizing women, is one of mutual support. In other words, while Jews might have provided information or services to crypto-Jews, at the same time the impoverished Jewish community sometimes turned to the conversos for support.

For example, poor Jewish men and women sometimes came to converso homes requesting alms. In the trial of Catalina Sánchez of Madrid (1502–1503), the conversa was accused not only of giving the community alms and oil for the synagogue, but of providing money for shrouds and proper burials for Jewish men and women who could not afford them. In 1509, Elvira Martínez of Toledo confessed to having employed a Jewish wet nurse because she was unable to find a Christian one. This same conversa had close relations with the Jewish community, for she also explained that she found refuge during a plague with a Jewish family, visited Jews during the holiday of Lit. "booths." A seven-day festival (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei to commemorate the sukkot in which the Israelites dwelt during their 40-year sojourn in the desert after the Exodus from Egypt; Tabernacles; "Festival of the Harvest."Sukkot was and occasionally received mazzah, fruit and other food from Jews.

A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover was often the catalyst for contact between the communities. Two conversa sisters testified to the fact that they entered a Jewish home and baked mazzah there together with the residents. In fact, there are many examples of conversas arranging to obtain mazzah on Passover, sometimes by purchasing it, sometimes by exchanging goods and sometimes by receiving gifts from Jews. Obviously, each crypto-Jewish woman had her own method of obtaining the unleavened bread and her own relationship with her Jewish suppliers.

Servants attested to the fact that Jewish women would enter the homes of conversa women; although they rarely knew why these visitations occurred, they sometimes noticed the presence of books or the fact that the women chose to meet in secluded portions of the house. Servants seem to have identified the Jewish visitors by their dress. One conversa confessed to having hired a Jewish woman to teach her to read, although she complained that it had not been a successful venture. In 1485, another conversa explained that she had lent her personal jewels to Jews for some of the festivals; this implies that there was a great deal of trust between these women.

The holidays often provided an opportunity for contact between the two groups, and many a converso visited a synagogue or a Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.sukkah was during the festival holiday. Sometimes the women gave their visitors refreshments. María González of Casarrubios del Monte sent her servants to obtain mazzah and other Jewish food from Jewish homes, obtained Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher was wine from her Jewish relatives or brought Jews to her home to make wine, sent for Sabbath stews if she had none at home, and received Jews in her home. The food and stews were being provided by Jewish women, either friends or relatives, who were generous with this conversa. After the birth of their children, conversas also invited Jewish friends and relatives to celebrate with them in a medieval ceremony called hadas; testimonies refer to having invited Jews and their wives as guests. Again, while the distinctions between Jew and crypto-Jew were clear to the Church, the women seemed not to make such clear-cut divisions and offered both moral and material support to one another.

After 1492: The Sephardi Diaspora

The final century of life in Spain was a troubled one for the Jews. The forced conversions of 1391 destroyed and divided their communities, but contacts between Jew and converso were common. In 1492, the fate of the Jewish community was sealed by the Edict of Expulsion. A substantial number chose to remain in Spain and, as a result, joined the conversos; the truth is that the presence of Jewish men and women who converted in 1492 injected new blood and knowledge into the crypto-Jewish community. From among this group, one can find followers of the messianic movement that developed in 1500, in particular in the village of Herrera. A substantial number of former Jewish women were tried by the Inquisition at this time because they were unable to maintain the façade of Catholicism despite their conversion.

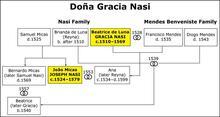

Among the families who chose exile, one can learn of women who proceeded to North Africa, Portugal, Italy, the Ottoman Empire and the Land of Israel. Some of these women were quite prominent, like Benvenida Abarvanel, who became a patroness of Jewish scholars and ventures in Ferrara, Italy and Doña Gracia of the House of Mendes-Nasi who was born in Portugal in 1510 to parents who were Spanish exiles. At the same time, the rabbinic literature reveals many of the complex legal problems experienced by these women: If a woman left Iberia and her husband refused to do so, did she need a divorce or was she to remain forever bound to him? If a man’s daughter accompanied him to resettle in a Jewish community whereas his son, living as a Catholic, did not, did she automatically inherit his estate? The rabbis were constantly attempting to trace the parentage of the conversos who left the Peninsula; if the mother was of Jewish origin, the converso or conversa would be recognized discreetly by the community. Although the Spanish Jews could no longer continue to live as Jews in their homeland after 1492, the Spanish Jewish way of life continued in the Sephardi Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora was. The language that survived, particularly in the Balkans and in Turkey, was Judeo-Spanish, a medieval Spanish infused with Hebrew words and phrases and originally written in Hebrew letters. The traditions, be they liturgical, culinary or ritual, continued, often for centuries; for example, hadas were still being celebrated in pre-World War II Salonika. The Spanish women were exiled, but their traditions remained with them and developed along with their communities in the Sephardi Diaspora.

Ashtor, Eliyahu. The Jews of Moslem Spain. 3 vols. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1984.

Assis, Yom Tov. The Jews of Santa Coloma de Queralt. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1988.

Baer, Yitzhak. A History of the Jews in Christian Spain. 2 vols. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1961, 1966, 1992.

Beinart, Haim. Trujillo: A Jewish Community in Extremadura on the Eve of the Expulsion from Spain. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1980.

Burns, Robert I. Jews in the Notarial Culture: Latinate Wills in Mediterranean Spain, 1250–1350. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996.

Dillard, Heath. Daughters of the Reconquest: Women in Castilian Town Society, 1100–1300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Hinojosa Montalvo, José. The Jews of the Kingdom of Valencia. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1993.

Klein, Elka. Power and Patrimony: the Jewish Community of Barcelona, 1050–1250. Ph.D. Dissertation, Harvard University: 1996.

Koch, Yolanda Moreno. La Mujer Judía. Córdoba: Ediciones El Almendro, 2007.

Lamdan, Ruth. A Separate People: Jewish Women in Palestine, Syria and Egypt in the Sixteenth Century. Leiden: Brill, 2000.

Leroy, Beatriz. The Jews of Navarre in the Late Middle Ages. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1985.

Levine Melammed, Renée. Heretics or Daughters of Israel: The Crypto-Jewish Women of Castile. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “The Jewish Woman in Medieval Iberia.” In The Jew in Medieval Iberia 1100-1500, edited by J. Ray, 257-285. Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2012.

Mirrer, Louise. Women, Jews and Muslims in the Texts of Reconquest Castile. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996.

Regne, Jean. History of the Jews in Aragon. Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1978.

Roth, Cecil. Doña Gracia of the House of Nasi. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1977.

Winer, Rebecca. Women, Wealth and Community: Christian, Jewish and Muslim Women in Thirteenth-Century Aragon. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2003.

Articles

Abad, Anna Rich. “Able and Available: Jewish Women in Medieval Barcelona and Their Economic Activities.” Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 6, no. 1 (2014): 71-86.

Assaf, Simha. “The Anusim of Spain and Portugal in the Responsa Literature” (Hebrew). Me’assef Zion 5 (1933): 19–60.

Assis, Yom Tov. “The ‘Ordinance of Rabbenu Gershom’ and Polygamous Marriages in Spain” (Hebrew). Zion 46 (1981): 251–277.

Assis, Yom Tov. “Sexual Behaviour in Mediaeval Hispano-Jewish Society.” Jewish History: Essays in Honour of Chimen Abramsky, edited by Ada Rapoport Albert and Steven J. Zipperstein, 25–59. London: Macmillan, 1988.

Beinart, Haim. “Judios y conversos en Casarrubios del Monte.” Homenaje a Juan Prado: Miscelánea de estudios biblicos y hebraicos, edited by Lorenzo Alvarez Verdes, 645–657. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1975.

Beinart, Haim. “Herrera: Its Conversos and Jews” (Hebrew). Proceedings of the Seventh World Congress of Jewish Studies B, 53–85. Jerusalem: N.p., 1981.

Bellamy, James A. “Qasmuna the Poetess: Who was She?” Journal of the American Oriental Society 103, no. 2 (1983): 423–424.

Cardoner Planas, A. “Seis mujeres hebreas practicando la medicina en el reino de Aragon.” Sefarad 9 (1949): 442–443.

Fleisher, Ezra. “About Dunash ben Labrat and his Wife and Son.” Jerusalem Studies in Hebrew Literature (Hebrew) 5 (1984): 189–202.

Grossman, Avraham. “From the Heritage of Spanish Jewry: Treatment of the ‘Killer’ Wife in the Middle Ages” (Hebrew). Tarbiz 67, no. 4 (1998): 531–561.

Grossman, Avraham. "The Struggle against Abandonment of Wives in Muslim Spain” (Hebrew). Hispania Judaica 10 (2014): 5-19.

Ifft Decker, Sarah. “Jewish Women, Christian Women, and Credit in Thirteenth-Century Catalonia.” The Haskins Society Journal 27 (2016): 161-178.

Klein, Elka. “Protecting the Widow and the Orphan: a Case Study from Thirteenth-Century Barcelona.” Mosaic 14 (1993): 65–81.

Klein, Elka. “Public Activities of Catalan Jewish Women." Medieval Encounters 12, no. 1 (2006): 48-61.

Klein, Elka. “The Widow’s Portion: Law, Custom and Marital Property among Medieval Catalan Jews.” Viator 31 (2000): 147–163.

Kraemer, Joel L. “Spanish Ladies from the Cairo Genizah.” Mediterranean Historical Review 6 (1991): 237–266.

Nichols, James Manfield. “The Arabic Verses of Qasmuna Bint Isma’il Ibn Bagdalah.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 13 (1981): 155–158.

Orfali, Moisés. “Influencia de las sociedades cristiana y musulmana en la condición de la mujer judía.” Árabes, judías y cristianas: Mujeres en la Europa medieval, edited by Celia del Moral, 77–89. Granada: Universidad de Granada, 1993.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “The Jews of Moslem Spain, A Gendered Analysis.” Journal of Sefardic Studies 2 (2014): 77-88.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “Sephardi Women in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods.” Jewish Women in Historical Perspective, edited by Judith R. Baskin, 128–147. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1999 (2nd ed.).

Winer, Rebecca. “Family, Community, and Motherhood: Caring for Fatherless Children in the Jewish Community of Thirteenth-Century Perpignan.” Jewish History 16, no. 1 (2002): 15–48.

Yahalom, Yosef. “The Manyo Letters: The Handiwork of a Country Scribe from North Spain” (Hebrew). Sefunot 7 (1999): 23–33.