Mela Muter

Mela Muter was one of the first women in Poland to devote herself to painting professionally. At the age of twenty-five, she left Poland for Paris. Her works were frequently exhibited in Poland, she participated in international Polish art exhibitions, and she showed her work throughout France and New York. Muter employed an artistic formula developed under the influence of post-impressionist painting. She painted landscapes and still lifes, and her portraits were greatly admired. Close to Paris bohemia, she also had many eminent people among her friends. Her sitters included Edgar Varese, Chana Orloff, and Diego Rivera, but she also often painted ordinary, anonymous people and children. While the many artistic currents of her epoch were reflected in her work, her painting was different from that of strict avant-garde.

Maria Melania Muter (née Klingsland) was one of the first women in Poland to devote themselves professionally to painting. At the age of twenty-five she left Poland and settled in Paris. Her works were frequently exhibited in Poland, she participated in international Polish art exhibitions, and always stressed that she considered herself Polish. She painted landscapes and still life and her portraits were greatly admired. Close to the Paris bohemia, she also had many eminent people among her friends. Her sitters included Edgar Varese (1883–1965), Chana Orloff, Diego Rivera (1886–1957) and August Perret (1874–1954), but she also often painted ordinary, anonymous people and children. Throughout her life she employed an artistic formula developed under the influence of post-impressionist painting. While the many artistic currents of her epoch were reflected in her work, her painting was different from that of strict avant-garde.

Early Life and Family

Muter was born in Warsaw into a polonised merchant family with patriotic and artistic leanings. Her father, Fabian Klingsland, supported artists, especially writers, such as the 1924 Nobel prize laureate in literature Wladyslaw Reymont (1868–1925). Her brother Zygmunt Klingsland, a Polish diplomat to Paris, was also a well-known literary critic.

Muter started to learn painting through private lessons. In 1899 she entered the School of Drawing and Painting for Women, headed by Professor Mi?osz Kotarbi?ski (1854–1944). In the same year she married Micha Mutermilch (1874–1947), a writer, critic and socialist activist from a polonised Jewish family. Their marriage took place at the Warsaw synagogue in Tłomackie street. Her only child, Andrzej, was born in the following year. Shortly afterwards, the family left for Paris. In autumn 1901 she started her studies at Académie de la Grande Chaumière, continuing them at the Académie Colarossi under the tuition of Etienne Tournés (1857–1931), Raphaël Collin (1850–1912) and René Xavier Prinet (1861–1946). She soon gave up academic studies, later claiming that she was self-taught and that she was influenced more by the painting of the École de Paris than by her college studies.

Early Works

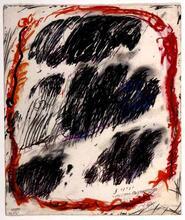

Her earliest surviving works belong to the symbolist school which was characteristic of Polish painting at the turn of the century. They are lyrical compositions, subdued in color and of delicate texture. During her first year in France the main influence on her was the contact she had with painters from École de Pont-Aven, which started during her frequent visits to Concarneau in Britanny. The influence of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) can also be detected in her paintings of this period. In France the colours of her painting became lighter and richer and the way of constructing the painting surface gradually changed. At first she painted using relatively flat and homogenous spots of color. Then she changed the way of putting paint on canvas, arriving at almost a pointillistic type of technique.

Her developed individual style was formed around 1905. Stylistic traits which she elaborated in her painting before WWI changed very little thereafter. The color range of her painting was light and matted, because she painted on a chalk underlay or on ungrounded canvas. The texture of her painting bears traces of short and distinct brush strokes. The paint was put on canvas in a nervous manner, in different directions, thus varying and breaking surfaces to attain an effect of vibration. She remained faithful to the subjects that interested her at the beginning of her artistic development. Portraits were of great importance to her, as were other figural compositions. She very often chose her models from among old, poor people and cripples. Pictures of children are a separate chapter in her painting. “Maternity” is another characteristic motif of her work—pictures of old, life-worn women carrying babies in their toil-worn hands. This kind of subject was linked to her social engagement. However, she treated such themes primarily as subjects for painting, like landscape and still life, though always with a distinct type of expression.

She began to exhibit her painting in 1902, her first individual exhibition taking place in Warsaw at the Society for Promotion of Fine Arts. This was only the second presentation by a woman artist in the history of the institution. In Paris she showed her works regularly at exhibitions organized by Societé Nationale des Beaux Arts, Salon des Indépendants, Salon d’Automne and Salon des Tuileries. In Poland she also participated in exhibitions at the Society for the Friends of Fine Arts in Kraków and Lvov. Before WWI, apart from the exhibition in Warsaw in 1902, she presented her work individually three times: in Warsaw in 1907, in Barcelona in 1911 and in Gerona in 1914.

Personal Life and Tragedy

In Paris she maintained contact with the numerous Polish artists, painters and writers who had settled there and participated in events organized by Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich (Polish Artists Society). Before WWI she travelled frequently to Spain, fascinated by Spanish landscapes and Spanish painting. She spent the war years mainly in France. In 1917 she met an intellectual and socialist activist, Raymond Lefebvre (1891–1920), who was severely ill at the time. Their relationship caused the breakdown of her marriage. A religious divorce from Micha? Mutermilch was granted by the Chief Rabbi of Paris in 1919. She cared for Lefebvre and, like him, took part in political activity. In 1918 she began co-operation with the magazine Clarté, in which she published pacifist drawings. Aligning herself with left-wing French intellectual circles, she met Romain Rolland (1866–1944), Anatole France (1844–1924) and Henri Barbusse (1873–1935). She planned marriage with Lefebvre, but this never took place, because Lefebvre went to Soviet Russia in 1920 and died in unexplained circumstances during a White Sea cruise. He was probably killed on Stalin’s orders. His death came as a great shock to Mela Muter, whose difficult situation was exacerbated by the illness of her son, who suffered from bone tuberculosis. She had already lost her mother (d. 1908/1909) and sister Gustawa Hirszberg (d. 1911). These tragedies combined to bring about her conversion to Catholicism in 1923.

In spite of all the tragedies, she never ceased painting and exhibiting. The influence of cubism is expressed in her work after 1919—a new interest resulting from her contact with Albert Gleizes (1881–1953), the French Cubist painter, and Gino Severini (1883–1966), the Italian Cubist/Futurist painter. In her memoirs she wrote that these two painters enabled her to understand that a painting “should not be composed but constructed.” Characteristic of her work from the beginning of the 1920s is geometrization and rhythmization of composition, which stressed the expressive aspects of her painting. But she later rejected cubism, describing it as “over-intellectualised because of artificial construction, which is harmful to the work.”

Interwar Period

In the period between the wars she held one-woman exhibitions in Paris in 1918, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1930 and in Warsaw in 1923. In 1921 she was invited to be a member of the Salon d’Automne jury.

When her son died in 1924, she again became immersed in deep depression. The death of her friend Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926) added to the tragedy.

Throughout these years she was known in the Paris milieu above all as a sought-after portrait painter. She created a very characteristic and easy-to-recognize formula in this field. With great talent she rendered visible both physiognomic and psychological traits, as well as the intellectual traits of her subjects. As models she liked above all talented and creative people with vivid intelligence, painting the portraits of many writers, composers and artists. She did not differentiate substantially between portrait painting and still life, and did not like it when others praised the psychological value of her portraits. She wrote: “I don’t ask myself whether a person in front of my easels is good, false, generous, intelligent. I try to dominate them and represent them just as I do in the case of a flower, tomato or tree; to feel myself into their essence; if I manage to do that, I express myself through their personality.” In her reflection on painting she revealed that she often approached natural forms by investing them with human traits. Landscape painting was the parallel form of her work. Motifs which recur in her painting are wide pastures, the architecture of southern France and often rivers and the life in their proximity.

Later Life and Career

In 1927 Mela Muter became a French citizen and her contacts with the Polish milieu in Paris became more detached. During this period her financial situation seriously deteriorated. At the beginning of the 1930s she started giving painting lessons. She leased out a villa designed for her by the architect August Perret and moved to her studio. She spent the war in the south of France, living in Avignon and teaching drawing, art history and literature at the girls’ College Ste. Marie. She received a small flat from the city authorities in which she spent her summer holidays until her death. After the war she was active in the pacifist movement and signed anti-war petitions by French women-painters and sculptors. She also founded a society for the protection of the Polish borders on the Oder and the Nysa. She continued to paint and exhibit a great deal. A large retrospective of her oeuvre took place in 1953 in Paris. She also showed her work in Lyon, Avignon, Marseille, Cologne and New York. In the 1950s she tried unsuccessfully to retrieve her villa, which she had rented to Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), and thus had to live in her humid, dark studio in the rue Pascal. She had serious problems with her sight, which improved after a cataract operation in 1965, so that she was able to rework some of her paintings. She died in her studio on May 14, 1967.

Mela Muter was the first professional Jewish woman painter in Poland. Leaving for Paris in 1901 she anticipated a tendency that became characteristic among Polish painters in the years that ensued. Her work is regarded as being a part of the École de Paris, in its broadest sense. She was an outsider all her life, uninfluenced by fashions or trends. Her portraits, landscapes and still life reveal the influence of major artistic currents of the turn and beginning of the century: synthetism of École de Pont-Aven, van Gogh’s expressionism, French fauvism, cubism. Yet her work was entirely individual, both in its subject matter and in the formal means which she employed.

Mela Muter. Collection of Bolesław and Lina Nawrocki (Polish). National Museum Catalog, Warsaw: 1994.

Polish Women Artists (Polish). National Museum Catalog, Warsaw: 1991.

Paris and Polish Artists Around E.-A.Bourelle 1900–1918 (Polish). National Museum Catalog, Warsaw: 1997.

Nieszawer N., M. Boye, and Foger P. Jewish Painters in Paris: École de Paris 1905–1939 (French). Paris: 2000.