Sarah: Midrash and Aggadah

Sarah, the first of the four Matriarchs, has come to symbolize motherhood for the entire world. The midrash presents her as a prophet and a righteous woman whose actions are worthy of emulation; she converted Gentiles and drew them into the bosom of Judaism. The changing of her name from Sarai was her reward for her good deeds and attests to her designation as a Sarah (i.e., one of the ruling ones) not only for her own people, but for all the peoples of the world. By merit of her good deeds, the people of Israel would merit certain boons; thus, for example, Israel received the manna in the wilderness by merit of the cakes that Sarah prepared for the angels.

Introduction

Sarah is described as preeminent in the household. Abraham was ennobled through her and subordinated himself to her; God commanded him to heed his wife, because of her prophetic power.

The Rabbis are lavish in their description of the beauty of Sarah, who was one of the four most exquisite women in the world and was regarded as the fairest, even in comparison with all the women in the nearby lands. Her barrenness was not perceived by the Rabbis as a punishment, and her pregnancy at the age of ninety was a reward for her good deeds. The Rabbis include in this wondrous occurrence additional miracles that she experienced when God remembered her: He formed a womb for her, and her entire body was restored to youthfulness. When God remembered her, all the crippled and deformed were healed, and all infertile women became pregnant. When she nursed, she could have done so for all the infants of the nations of the world, without wanting for milk; in the wake of this nursing, many Gentiles entered Judaism.

Sarah’s untimely death is perceived as related to the Binding of Isaac. She was the first of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs to be buried in the Cave of Machpelah. Her distinguished funeral teaches of the great esteem in which she was held by the inhabitants of the land, who all locked their doors and came to pay their respects to Sarah.

The different traditions tell of Sarah’s role in spreading the name of God throughout the world. Her maternity expanded and came to symbolize the warm bosom of Judaism, both for her future descendants and for all the world.

Family Ties

Abraham and Sarah were related before they married. Abraham says (Gen. 20:12): “And besides, she is in truth my sister, my father’s daughter though not my mother’s; and she became my wife.”

The Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah relates of their marriage (Gen. 11:29): “Abram and Nahor took to themselves wives, the name of Abram’s wife being Sarai and that of Nahor’s wife Milcah, the daughter of Haran, the father of Milcah and Iscah.” The special structure of this verse led the rabbis to identify Iscah with Sarah; thus, Abraham married his brother’s daughter (BT Sanhedrin 69b).

One tradition has Sarah being born to Haran when he was only eight years old, but others dispute this calculation (BT Sanhedrin 69b; see also Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder Olam Rabbah 2).

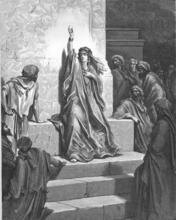

Sarah the Prophet and Righteous Woman

The A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash asserts that all the Patriarchs and Matriarchs were termed “prophets” (Seder Olam Rabbah 21). The Rabbis note that God himself attested to Sarah’s being a prophet when He told Abraham (Gen. 21:12): “Whatever Sarah tells you, do as she says” (BT Sanhedrin loc. cit.). Another exegetical tradition lists Sarah among the seven women prophets, the others being Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah and Esther. Her prophetic ability is also learned from her name Iscah, for she saw [sokah] the spirit of divine inspiration (BT Lit. "scroll." Designation of the five scrolls of the Bible (Ruth, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The Scroll of Esther is read on Purim from a parchment scroll.Megillah 14a).

The Rabbis applied to Sarah Prov. 12:4: “A capable wife [eshet hayyil] is a crown for her husband.” While she was not ennobled through her husband, he was ennobled through her. She is also called her husband’s “lady,” or mistress of the house. Everywhere it is the husband who has the final word, but here (Gen. 21:12), “Whatever Sarah tells you, do as she says” (Gen. Rabbah 47:1). The midrash further tells that on their journeys Abraham would first erect Sarah’s tent before he tended to his own (Gen. Rabbah 39:15).

Regarding Sarah’s good attributes, it is said that Abraham and Sarah converted the Gentiles. Abraham would convert the men, and Sarah, the women. These converts are (Gen. 12:5) “the persons [nefesh, literally souls] that they acquired [asu, literally, made] in Haran,” because if anyone converts a Gentile, it is as if he created him (Gen. Rabbah 39:14).

Sarah’s Beauty

The Rabbis praise Sarah’s beauty, including her among the four most beautiful women in the world together with Rahab, Abigail and Esther (BT Megillah loc. cit.). Even Abishag the Shunammite was not half as beautiful as Sarah (BT Sanhedrin 39b). To portray Sarah’s beauty, the Rabbis say that, in comparison to her, all other people are as a monkey to humans. Of all women, only Eve was comelier (BT Bava Batra 58a). The exegetes also learned of her beauty from her name Iscah, since all would gaze [sokim] upon her beauty (Sifrei on Numbers, 99). It is further related that throughout the ninety years that she did not give birth, Sarah was as beautiful as a bride under her bridal canopy (Gen. Rabbah 45:4).

Sarah’s beauty is not mentioned when she appears for the first time in the Torah (Gen. 11:29); we first learn of it when Abraham and Sarah go down to Egypt because of the famine in Canaan, in Gen. 12:11: “As he was about to enter Egypt, he said to his wife Sarai, ‘I know what a beautiful woman you are.’” The midrash asks on this: [Sarah] was with [Abraham] all those years, and it is only now that he says to her: “I know what a beautiful woman you are”? Was it only now that Abraham paid attention to his wife’s beauty? Several answers are offered. One is that people usually become debased by the rigors of the journey, while Sarah retained her beauty (Gen. Rabbah 40:4). According to this answer, Abraham was conscious of his wife’s pulchritude, but now he was amazed at the fact that she retained her beauty even after their wanderings from Canaan to Egypt.

Another response explains that Abraham tells Sarah: “We passed through Aram-Naharaim and Aram-Nahor, and we did not find a woman as beautiful as you. Now that we are entering a place of the ugly and the black [i.e., Egypt], ‘Please say that you are my sister’” [Gen. 12:13] (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). This answer, too, indicates that Abraham was aware of his wife’s loveliness, but now that he had crossed several countries, he knew that her beauty exceeded that of all the women in Aram-naharaim, in Aram-nahor, and obviously those in Egypt, which causes him to be so fearful. It may be concluded from the midrashic appellation for Egypt, “a place of the ugly and the black,” that Sarah was fair skinned, in contrast to the Egyptians. Sarah’s beauty is depicted at length in a Jewish composition from the first century BCE (Genesis Apocryphon [ed. Avigad-Yadin], 36).

Abraham and Sarah Go Down to Egypt

Abraham told his wife Sarah: “There is a famine in the land the likes of which the world has never known. It is fine to dwell in Egypt; let us go there, where there is much bread and meat.” The two went, and when they arrived in Egypt and stood on the banks of the Nile, Abraham saw Sarah’s reflection in the river as a dazzling sun. He said to her: “I know [yadati, literally, I knew] what a beautiful woman you are.” The Rabbis deduced from the wording yadati that, prior to this, he had not known her as a woman (Tanhuma, Lekh Lekha 5).

The rabbis wondered why Gen. 12:14 states: “When Abram entered Egypt,” without mentioning Sarah. In the midrashic explanation, Abraham tried to conceal her from the Egyptians by putting her in a chest that he locked. When he came to the tax collectors, they ordered him: “Pay the tax,” he said: “I will pay.” They asked him: “Do you have vessels in the chest?” He replied, “I will pay the tax on vessels.” They asked him: “Are you bringing silk garments?” He replied: “I will pay the tax on silk garments.” They asked him: “Are you bringing pearls?” He said: “I will pay the tax on pearls.” They told him: “We cannot let you go on your way until you open the chest, and we see what it contains.” When they opened it, all the land of Egypt was resplendent with her beauty [literally, light] (Gen. Rabbah 40:5; see the variant in Tanhuma, Lekh Lekha 5). This exposition defends Abraham’s conduct as it is described in the Torah.

The midrash presents Abraham as one who cherishes his wife and is not willing to part with her. Abraham is willing to pay any amount of money to keep Sarah. Sarah, in turn, is portrayed as someone whose value is greater than all the money in the world. The light that she radiates when the chest is opened graphically illustrates that she is worth more than all the pearls in the world.

When the tax officials see Sarah, they exclaim: “This one is not suitable for a commoner, but for the king” (Tanhuma loc. cit.). According to another tradition, one said: “I will give a hundred dinars and I will enter the royal palace with her.” Another said: “I will give two hundred dinars and I will enter the royal palace with her,” thus Sarah’s [monetary value] kept increasing (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

In the midrashic tableau, when Abraham saw that Sarah had been taken to the palace of Pharaoh, he began to weep and pray to God. Sarah, too, cried out, saying: “Master of the Universe! when I heard from Abraham that You had told him, ‘Go forth,’ I believed in what You said. Now I remain alone, apart from my father, my mother, and my husband. Will this wicked one come and abuse me? Act for Your great name, and for my trust in Your words.” God replied: “By your life, nothing untoward will happen to you and your husband.” At that moment, an angel descended from Heaven with a whip in his hand. Pharaoh came to remove Sarah’s shoe—he hit him on the hand. He wanted to touch her clothing—he smote him (Tanhuma loc. cit.). All that night the angel stood there with the whip. If Sarah bade him “Strike,” he would strike him. If she told him “Cease,” he ceased. Even though Sarah told Pharaoh: “I am a married woman,” he did not desist from his efforts to touch her (Gen. Rabbah 41:2). These traditions emphasize what the Torah does not state that nothing indecent happened between Sarah and Pharaoh. The midrashim present Pharaoh as someone who knows that Sarah is a married woman, but nonetheless desires her. Sarah is depicted as a strong woman, whose purity is protected by God by merit of her faith.

As for the afflictions with which Pharaoh and his household were punished, the midrash adds that his ministers were similarly stricken, as it says (Gen. 12:17): “and his household”—including slaves, walls, pillars, vessels and all things. These plagues were worse than any affliction that ever came, or would ever come, upon human beings (Tanhuma loc. cit.).

In the midrashic account, Abraham and Sarah stayed in Egypt for three months, after which they returned to Canaan and dwelled “at the terebinths of Mamre which are in Hebron” (Gen. 13:14). They were accompanied by Hagar, whom Pharaoh had given as a present to Sarah. They dwelt in the land of Canaan for ten years, and then Abraham married Hagar (Seder Olam Rabbah 1).

The Barren Woman

The midrash lists Sarah among the seven barren women who were eventually blessed with offspring: Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, Leah, Manoah’s wife, Hannah and Zion (metaphorically), of whom Ps. 113:9 states: “He sets the childless woman among her household as a happy mother of children” (Pesikta de-Rav Kahana [ed. Mandelbaum], Roni Akarah 20:1).

The infertility of the Matriarchs troubled the Rabbis, since barrenness was thought to be a punishment, while these women were righteous. Moreover, they were chosen by God to be the Matriarchs of the nation; it is incomprehensible how they could fulfill their destiny if they could not bear children. The Rabbis suggested several answers to this question (see the the section “Barren” in Rebekah).

The statement in Gen. 16:1 that relates of Sarah’s barrenness: “Sarai, Abram’s wife, had borne him no children,” is the subject of a disagreement among the Rabbis. According to one opinion, Sarah did not bear children to Abraham, nor was she capable of bearing to any other man. According to a second view, Sarah “had borne him” no children, but if she had been married to another, she would have given birth (Gen. Rabbah 45:1). The second school of thought suggests that Abraham was infertile, and therefore Sarah did not give birth. This view is also expressed in the BT, which states that Abraham and Isaac were infertile, because God longs for the prayer of the righteous (BT Yevamot 64a).

According to yet a third understanding, both Abraham and Sarah were infertile; they were tumtumin (with underdeveloped genitals), and God had to hew sexual organs for them so that they could procreate. According to yet another view, however, Sarah was not a tumtumit, but an ailonit (a woman incapable of procreation), and even lacked a womb (BT Yevamot 64b). The purpose of these midrashim is to magnify the dimensions of the miracle that was performed for Abraham and Sarah when their prayer was answered. Not only did they bear a child after many years of infertility, and at an advanced age; God opened their sexual organs, or even formed a womb for Sarah. Her womb was fashioned especially for the birth of Isaac, who would be the progenitor of the entire people of Israel.

Sarah Gives Abraham Her Handmaiden Hagar

When Sarah saw that ten years had passed for them in Canaan and she was still childless, she told Abraham: “I know the source of my infirmity. It is not as they say of other women: ‘She needs an amulet,’ ‘She needs a charm,’ rather (Gen. 16:2): ‘Look, the Lord has kept me from bearing’” (Gen. Rabbah 45:2). The Rabbis learned from the story of Abraham and Sarah that if a man is married for ten years and his wife bears no children, he may not be excused from his obligation of procreation (and he must take another, or an additional, wife). They further derived that the time one dwells outside The Land of IsraelErez Israel is not included in this count, for it says (Gen. 16:3): “after Abram had dwelt in the land of Canaan ten years”; consequently, the count of ten years started only when they began to dwell in the land of Canaan, and not when they were in Egypt (BT Yevamot 64a).

Sarah told Abraham (v. 2): “Consort with my maid; perhaps I shall have a son [or: be built up] through her.” The Rabbis deduced from this that anyone who is childless is like a ruined structure that must be rebuilt. Abraham heeded his wife Sarah and the spirit of divine inspiration within her (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). Sarah took Hagar and gave her to Abraham, which the midrash understands as Sarah enticing her with words. Sarah told her: “Happy are you, in that you will cleave to a holy body [Abraham]” (Gen. Rabbah 45:3).

Hagar, Sarah’s Rival Wife

The Rabbis portray Hagar as not showing proper respect to her mistress Sarah, and as one who caused other women to make light of her (i.e., of her worth and standing). Hagar took advantage of her pregnancy to besmirch her mistress’s good name (see Gen. Rabbah 45:4 and the entry Hagar). Sarah is depicted in these expositions as a noble woman who is aware of her station and has no intention of descending to the level of her handmaiden. She does not argue with Hagar, thus highlighting the moral and class difference between them.

The Rabbis were troubled by the question of how it was that the righteous Sarah did not conceive from Abraham for more than ten years, while Hagar became pregnant immediately. They explain that Hagar gave birth to Ishmael with such ease because he is like worthless thorns, in contrast to Sarah’s future birth of Isaac, who would continue in Abraham’s path, and whose conception required much effort and exertion. Sarah’s difficulty in conceiving therefore attests to the quality of the descendant she would produce (see Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). For a description of the tension between Hagar and Sarah, for the criticism that Sarah leveled at Abraham, and Hagar’s harsh treatment by Sarah, see the entry Hagar.

In the midrashic account, when Hagar became pregnant, Sarah told Abraham: “I demand justice from you [before God]! You said [Gen. 15:2]: ‘seeing that I shall die childless,’ and your prayer was heard. If you had said, ‘seeing that we shall die childless,’ what God granted you, He would also have granted me! You said [v. 3]: ‘Since You have granted me no offspring’—if you had said, ‘Since You have granted us no offspring,’ as He granted you, He would have granted me, too!” (Two parables are presented in connection with this subject; see Gen. Rabbah 45:5.)

Changing Her Name from Sarai to Sarah

Gen. 17 relates that God was revealed to Abraham, commanded him regarding circumcision, and informed him of the change of his name, and of that of Sarai to Sarah. In the midrashic expansion, Abraham says to God: “I see that, in the stars, Abram does not bear children.” God replied: “What you say is so. Abram and Sarai do not bear children, but Abraham and Sarah do bear children” (Gen. Rabbah 44:10).

As regards the significance of this change, the Rabbis explain that initially she was a princess [sarai] over her people, while now she will be a princess over all the inhabitants of the world [sarah] ((Aramaic) A work containing a collection of tanna'itic beraitot, organized into a series of tractates each of which parallels a tractate of the Mishnah.Tosefta Berakhot [ed. Lieberman] 1:13). In an additional exegetical explanation, because Sarai performed good deeds, God added a large letter to her name, and she would now be called “Sarah” (Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Masekhta de-Amalek, Yitro 1). The Rabbis determined that whoever now called Sarah by her former name transgressed a positive commandment (JT Berakhot 1:6, 4[a]).

The midrash relates that the letter yud that was taken from Sarai’s name flew up before God. It complained: “Master of all the worlds! because I am the smallest of all the letters, You removed me from the righteous woman’s name?” God replied: “Before, you were in a woman’s name, and at the end of her name, now I put you in a man’s name, and at the beginning of the name [Num. 13:16]: ‘but Moses changed the name of Hosea [hoshe’a] son of Nun to Joshua [yehoshua]’” (Gen. Rabbah 47:1). According to another tradition, half of the letter yud [with the numerical value of ten] that God took from Sarai was given back to Sarah, and the other half was given to Abraham [each received the letter heh = 5 + 5] (JT Sanhedrin 2:6, 20[c]).

After God changed Sarai’s name, He further said (Gen. 17:16): “I will bless her; indeed, I will give you a son by her. I will bless her.” The Rabbis understand that the first blessing was that she would give birth to a son, and the second, that she would have milk. According to another exegesis, God blessed Sarah by forming a womb for her. In a third view, the blessing did not focus solely on the issue of birth, but extended to her entire being, which became young again. A fourth opinion derives the nature of the blessing from the continuation of this verse: “I will bless her so that she shall give rise to nations.” The meaning of the blessing, which relates to Sarah’s standing in the eyes of the nations, is that Sarah will be respected by the Gentile peoples, who will no longer call her barren. The midrash adds that Sarah conceived that very same year (Gen. Rabbah 47:2).

The Visit by the Three Angels

The midrash specifies that the three angels who visited Abraham and Sarah were Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. Michael came to inform Sarah of the birth of Isaac, Raphael came to heal [le-rape] Abraham after his circumcision, and Gabriel came to annihilate Sodom (BT Bava Mezia 86b). On the fifteenth day of Nisan (the first day of A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover) the angels came to bless Sarah, on the fifteenth of Nisan Isaac was born, and on the fifteenth of Nisan the Israelites went forth from Egypt (Seder Olam Rabbah 5). This midrash imparts special significance to the day on which Sarah was informed of Isaac’s future birth and to the day of his birth. The identification of this date as the historic date on which the Israelites went forth from Egypt links together all the promises made by God to Abraham at the covenant between the pieces: offspring, servitude, redemption, and the inheritance of the land (see Gen. 15).

When the angels came to the tent, Abraham said to Sarah (Gen. 18:6): “Knead and make cakes!” The Rabbis observe that the mazzot that the Israelites prepared when they left Egypt were also called (Ex. 12:39) “unleavened cakes,” from which they learned that the cakes that Sarah prepared for the angels were mazzot, for they came to the couple during Passover. The midrash adds that by merit of the cakes that Sarah prepared for the angels, the Israelites were given manna in the wilderness (Gen. Rabbah 48:12).

The Rabbis noted that when Abraham serves the food to the angels, no mention is made of the cakes that Sarah prepared. According to one exegetical view, that day Sarah saw the first signs of her menstrual period. Care was taken in Abraham’s household to eat all foods in purity, and he therefore did not serve the cakes that Sarah had prepared (Gen. Rabbah 48:14). This midrash teaches of the fulfillment of God’s promise to restore Sarah’s youth, which happened on the same day on which the angels appeared and informed Sarah of the birth of Isaac.

When the angels wished to bless Sarah, they asked Abraham (Gen. 18:9): “Where is your wife Sarah?,” to which he replied (ibid.): “There, in the tent.” The Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud maintains that their question was meant to teach us of Sarah’s modesty (because she remained in her tent, even when guests came). According to another interpretation, the ministering angels knew that Sarah was in the tent, but they asked about her so that she would be beloved by her husband (in order that he would mention her and her good traits). Yet another reason given for their question: they did so to send her the cup of blessing (BT Bava Mezia 87a).

When Sarah heard the prophecies by the angels, she laughed to herself, and said (Gen. 18:12): “Now [literally, “after”] that I am withered, am I to have enjoyment—with my husband so old?” The rabbis understood her statement not as amazement, but as a depiction of the change that she would undergo in the wake of this prophecy. “After I am withered”—after her skin withered and was full of wrinkles, “am I to have enjoyment [ednah]”—her flesh miraculously was rejuvenated [nitaden], her wrinkles vanished, and her former beauty returned (BT Bava Mezia loc. cit.). Another exegesis derives the word ednah from adi (jewel). Sarah said: “As long as a woman gives birth, she is adorned; after I grew old, now I am adorned.” Yet another etymological exegesis derives ednah from eidan, the time of a woman’s period. Sarah said: “As long as a woman gives birth, she has periods, and I, after I grew old, had a woman’s period” (Gen. Rabbah 48:17).

The Rabbis discerned that when Sarah responds, she says (v. 12): “with my husband so old,” but when God repeats her statement to Abraham in v. 13, He says: “old as I am” (i.e., Sarah related, as it were, to her own old age). This teaches the greatness of peace: even God changed Sarah’s words for the sake of peace between man and wife (BT Bava Mezia loc. cit.). In order that Abraham not be offended by what his wife said, and to prevent a quarrel between them, God altered Sarah’s statement.

The prophecy of Sarah’s becoming pregnant is delivered to Abraham and Sarah hears this from her tent. Only three words are addressed directly to her (Gen. 18:15): “You did laugh.” The midrash comments that Sarah is the only woman with whom God converses directly. God never had to speak with a woman, except for that righteous woman, and that only for a good reason [He spoke with Sarah only after she denied having laughed]. How many circuits did He make before He addressed her [how much effort did God show in order to speak with her]! (Gen. Rabbah 48:20).

And the Lord Took Note of Sarah—the Birth of Isaac

The Rabbis say that a special angel is appointed for desire and pregnancy, yet Sarah was not visited by an angel, but by God Himself, as it says (Gen. 21:1): “The Lord took note of Sarah.” The Rabbis ascribe Sarah’s pregnancy to her good deeds: the Torah says, “The Lord took note [pakad] of Sarah,” because the Lord is the master of deposits [pikdonot]. Sarah deposited with Him commandments and good deeds, and He returned to her commandments and good deeds [by giving her Isaac]. According to another exegetical position, Sarah merited becoming pregnant by a specific incident: for entering the houses of Pharaoh and of Abimelech and emerging pure. Since she was proper in her sexual conduct, she merited pregnancy.

Isaac was born after nine full months of pregnancy, so that it would not be said that he was from the seed of Abimelech. In another view, the pregnancy extended for seven full months, that are nine incomplete months [i.e., a part of the first month, the seven in the middle, and a part of the last] (Gen. Rabbah 53:5–6). The first opinion is based on the juxtaposition of the narrative of Sarah in the house of Abimelech (Gen. 20) with her conceiving (Gen. 21). The second expressed the well-known Rabbinic position that Sarah became pregnant on The Jewish New Year, held on the first and second days of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. Referred to alternatively as the "Day of Judgement" and the "Day of Blowing" (of the shofar).Rosh Ha-Shanah, and Isaac was born in Nisan (BT Rosh Hashanah 10b); consequently, her pregnancy extended for only seven months. It is therefore still customary to read Gen. 21:1: “The Lord took note of Sarah” on Rosh Hashanah (BT Megillah 31a).

The midrash relates that when Sarah became pregnant, all the barren women became pregnant, all the deaf became capable of hearing, all the blind were given sight, all the mutes were cured, and all the madmen became sound of mind. All said: “Would that He take note of Sarah a second time, that we, too, could have been remembered with her!” (Pesikta de-Rav Kahana, Sos Asis 22:1).

Isaac was born in the middle of the day on Nisan 15, at precisely the same time that the Israelites would go forth from Egypt (Seder Olam Rabbah 5; Gen. Rabbah 53:6).

The Torah states that when Abraham weaned his son Isaac he held a great feast (Gen. 21:8). In the midrashic expansion, all the nations of the world gossiped and said: “Did you see that old man and old woman, who brought a foundling from the marketplace, and claim that he is their son? And this is not all—they are holding a great feast, so that what they say will seem to be the truth!” What did Abraham do? He went and invited all the great ones of the generation, and Sarah invited their wives. Each one brought her baby with her but did not bring the wet nurse. A miracle was performed for Sarah: her breasts opened like two fountains, and she nursed them all. Gen. 21:7 therefore declares: “that Sarah would suckle children”—that she nursed the children of all the women (BT Bava Mezia 87a).

In another tradition, the nations of the world would say: “It was not Sarah who gave birth to Isaac, rather Hagar, Sarah’s handmaiden, gave birth to him!” What did God do? He withered up the breasts of the women of the nations of the world. Their noblewomen would come and kiss the ground at Sarah’s feet, and they said to her: “Do a good deed and nurse our children.” Abraham told Sarah: “Sarah, this is not the time for modesty. Sanctify God’s name. Sit down in the marketplace and nurse their children” (Pesikta de-Rav Kahana loc. cit.).

Sarah stood and revealed herself, and her two breasts spouted milk like two spouts of water. The nations of the world brought their children to Sarah for her to nurse. Some brought their children so that she would nurse them, and others brought their children to examine this. Neither lost. Those who came sincerely converted, and therefore it is said, “she would suckle children [banim],” that they would be built [shenitbanu] in Israel. And those who came to examine were elevated in this world, with honor and greatness [but since they set themselves apart, rulership was taken from them]. All those who convert in the world, and all those who fear God in the world, are from among those who nursed from Sarah (Pesikta Rabbati [ed. Friedmann (Ish-Shalom)], para. 43).

Despite this, people still murmured and said: “Will Sarah, who is ninety years old, give birth? Will Abraham, who is a hundred years old, beget children?” Isaac’s countenance immediately changed to resemble that of Abraham. All of them then declared (Gen. 25:19): “Abraham begot Isaac!” (BT Bava Mezia loc. cit.).

Sarah’s Death and Burial

Sarah died at the age of 127, which was young in comparison to Abraham, who lived to the age of 175. The Rabbis explain that Sarah died before her time out of fright and connected her death with the Binding of Isaac. Although Sarah does not appear in the Binding narrative, this is the last event to be mentioned before her death. The midrash tells that Isaac was concerned about his mother’s welfare, and when he was tied to the altar and thought that he was about to die, he asked of his father: “Father, do not tell my mother [of my death] when she is standing by a pit or when she is standing on the roof, lest she cast herself down and die.” That moment a heavenly voice went forth and said to Abraham (Gen. 22:12): “Do not raise your hand against the boy.”

Satan went to Sarah and appeared to her in the countenance of Isaac. When she saw him, she said to him: “My son, what has your father done to you?” He answered her: “Father took me and raised me up to the mountains and brought me down into the valleys. He took me up to the top of one mountain, built an altar, arranged the woodpile, and placed the logs. He bound me on the altar and took a knife to slaughter me. If God had not told him: ‘Do not raise your hand against the boy,’ I would already be slaughtered.” Satan did not finish speaking, and Sarah passed away (Tanhuma, Vayera 23). It therefore is said (Gen. 23:2): “And Abraham proceeded [va-yavo, literally, and he came] to mourn for Sarah”—where did he come from? from Mount Moriah (Gen. Rabbah 58:5). This early aggadic tradition is depicted in a synagogue mural in Dura-Europus (an ancient city on the Euphrates), with a portrayal of Isaac, and at a distance, Sarah gazing upon the scene from within her tent.

In another tradition, Sarah dies prematurely because she was punished for telling Abraham (Gen. 16:5): “The wrong done me is your fault! […] The Lord decide between you and me!” Whoever calls down Divine judgment on his fellow is himself punished first; consequently, Sarah died before Abraham (BT Rosh Hashanah 16b).

The units of the count of Sarah’s life—hundreds, tens, and units—are listed separately (Gen. 23:1): “Sarah’s lifetime came to one hundred and twenty-seven years [literally: “one hundred years, and twenty years, and seven years”], from which the Rabbis found evidence of her merit: when she was twenty, she was as seven for beauty […] when she was one hundred, she was as twenty for sin (Gen. Rabbah 58:1).

In the midrashic recounting, Abraham was unsuccessful when he searched for a place to bury Sarah. God had promised him (Gen. 13:17): “Up, walk about the land, through its length and breadth, for I give it to you.” Despite this, he had to purchase the Cave of Machpelah from Ephron the Hittite for four hundred shekels of silver. Nonetheless, he did not question God’s attributes (BT Sanhedrin 111a).

Sarah was buried in Kiriath-Arba, which was so named, as the Rabbis explain, because the four [arba] matriarchs were buried there: Eve, Sarah, Rebekah, and Leah (Gen. Rabbah 58:4). Another etymology explains that it was given this name on account of the four couples interred there: Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and Jacob and Leah (BT Eruvin 53a).

The midrash states that all the inhabitants of the land locked their doors and came to pay their respects to Sarah [by accompanying her funeral] (Gen. Rabbah 58:7). All those who accompanied Sarah to her final resting place merited to do so for Abraham, as well [they enjoyed longevity, and lived an additional thirty-eight years, so that they would also be present at Abraham’s funeral] (Gen. Rabbah 62:3).

According to one tradition, Shem and Eber walked before Sarah’s bier. They saw an empty chamber in the Cave of Machpelah, that was intended for Abraham’s burial, and they interred Sarah in the place that was designated for him. Therefore it is said: “there Abraham was buried, and Sarah his wife,” for they were buried together (Gen. 25:10).

In the Time of the Rabbis

The midrash relates that R. Akiva was standing and expounding, and he saw that his listeners were drowsing. Seeking to awaken them, he asked: “Why did Esther reign over 127 provinces in the kingdom of Ahasuerus? Esther, who is the daughter of the daughter of Sarah, who lived for 127 years, will come, and she will rule over 127 provinces” (Gen. Rabbah 58:3). Although R. Akiva spoke in jest, to arouse his listeners, his exposition creates an interesting connection between these two important women in Jewish history. One, who was named “Sarah” (see above), was a princess over nations, and the other, one of her descendants, was a queen over many provinces.

The Talmud relates that R. Bana’ah would mark out tombs [for the observance of the ritual purity laws]. When he came to Abraham’s cave, he found his servant Eliezer standing before the entrance. R. Bana’ah asked him: “What is Abraham doing?” Eliezer replied: “He is lying in the embrace of Sarah, and she is looking fondly at his head.” R. Bana’ah told Eliezer: “Go tell him that Bana’ah is standing at the entrance.” Abraham told Eliezer: “Let him enter.” The Rabbis comment that: “It is well-known that the sexual urge exists only in this world.” R. Bana’ah entered, surveyed the cave, and went out (BT Bava Batra 58a).

This midrash describes Abraham and Sarah’s “life” in the Cave of Machpelah as the continuation of their existence in the world. The hierarchy continues, the servant stands at the entrance to serve them and guards their privacy. The depiction of Abraham in Sarah’s bosom is one of tranquility and harmony and reflects the closeness and love of their relationship. This tableau clearly shows that, despite the numerous tensions with Hagar, and despite Abraham’s marriage to Keturah, Sarah was, and remained, the only woman in his life, and it is with her that he spends the life after death. The fact that Abraham lies in the bosom of Sarah, and not the opposite, perpetuates their relationship, as it was described by the Rabbis. Abraham subordinates himself to Sarah: she is the mistress of the house, and he is ennobled through her.