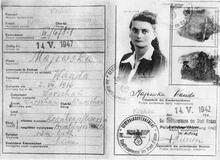

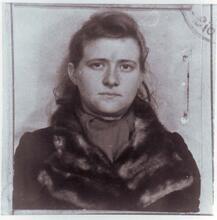

Poland: Women Leaders in the Jewish Underground During the Holocaust

Women played an unusually prominent role in the Jewish underground in German-occupied Eastern Europe. Pictured here are three of the important leaders of the resistance in the Vilna Ghetto (L to R): Zelda Nisanilevich Treger, Rozka Korczak-Marla and Vitka Kempner-Kovner.

Institution: Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

There were prominent female leaders in nearly every Jewish underground in the Polish ghettos during WWII. These women emerged from socialist egalitarian Jewish youth movements which continued their activities during the war. Between 1940 and 1942, women occupied central leadership positions in these youth movements inside the ghettos. The establishment of ghettos also necessitated the creation of a new functionary – a delegate to central leadership who could move between ghettos. These delegates were most often women, and they functioned like high-ranking staff officers in a military organization. Jewish fighting organizations relied on these delegates to deliver arms and military instructions between ghettos. Although men filled most of the fighting roles themselves, some women did serve as commanders. A dual leadership structure, composed of one man and one woman, was common within the Jewish underground.

Introduction

The women activists of the Jewish underground during the Holocaust have been variously memorialized: as virtually mythic “heroic girls” (as Emanuel Ringelblum in the Warsaw Ghetto and Ya’akov Hazan in Israel in the 1940s termed them) and as “courier girls” (as they are more mundanely referred to in modern studies). The true description of women’s role in the Jewish underground may lie somewhere between these two extremes.

The presence of so many young women in the Jewish Underground leadership and their unique role within this leadership are unusual phenomena, not only against the background of a pre-feminist era, but even in comparison with social and political organizations today. In fact, in almost every underground leadership in the Polish Ghettos one can find one or more dominant feminine figures: Zivia Lubetkin and Tosia Altman in Warsaw; Haika Grosman in Bialystok; Vitka Kempner-Kovner and Rozka Korczak-marla in Vilna; Rivka Glanz in Czestochowa; Gusta Dawidson draenger (Justina) and Mire Gola in Cracow; Chajka Klinger, Frumka Plotniczki and Fredka Oxenhendler Mazia in Zaglembie (Zaglebie Dabrowskie) and so on. All of these women were active members of the leadership, had a significant influence on the decision-making processes and were at times leading figures in resistance operations. In short, they were leaders.

The Roots of Jewish Female Leadership

The roots of this unique phenomenon can be found in two overlapping traditions—respectively that of revolutionary Europe and that of the Jewish youth movements. In the second half of the nineteenth century, women held leading positions in revolutionary movements: Vera Figner (1852–1942) in the Narodniks movement in Russia; Vera Zasulich (1849–1919) in the anarchist and social democrat movement in Russia; Rosa Luxemburg in the Polish, Russian and German Social Democracy movement; Emma Goldman, an American anarchist; Mania Shochat (Wilbushewitch) and the young Golda Meyerson (Meir) in Zionism; Dolores Ibarruri (Gomez), La Pasionaria (1895–1989) in the Spanish Civil War. These women were able to emerge as leaders because of the relative egalitarian and anarchist characteristics of their respective movements.

The Jewish movement studied the new phenomenon of female revolutionaries during the time between the two world wars. Stories about Figner, Luxemburg and Shochat were told by the campfire at open-air sessions held by youth movements and published in their pamphlets. Their images were presented as role-models, thus shaping the youngsters’ ideals.

In addition, the Jewish youth movements had their own values and norms, which devised a new social position for Jewish girls. Most of the movements were radical socialist or bore the impact of socialism in one way or another. The equality of women within the social framework was taken for granted since it derived from the idea of equality among all human beings. In this new social context the girls had some advantages over the boys. Most of the youth movement members were under eighteen years of age. In such groups the level of maturity of the girls was clearly superior to that of the boys, with the result that the girls naturally assumed key roles. In consequence, many young women later advanced to central positions in the movement leadership.

The concept of the “intimate group” which originated with Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir and was emulated by many other Jewish youth movements also strengthened the girls’ status in another respect. The individual youth movement groups served as a fraternity or small family in which an emotional attraction, common to both sexes in the group, was a crucial factor. Personal relationships between the members of the group were openly discussed and enhanced the status of the girls as indispensable members of the intimate group. Again, it seems that the relative maturity of the girls, together with the emphasis on their emotional importance within the group, reinforced their role within the group.

In addition, the intimate group functioned like a family, which had not only its “brothers” and “sisters” but also its “father” and “mother.” These were the male and female youth leader respectively, who represented parental figures for the youngsters. In some branches, there was a separation between girls and boys, each group with leaders of the same sex. Study of two same-age single-sex groups of boys and girls who shared numerous activities reveals that the family structure was also preserved in this formation.

These characteristics of the Jewish youth movement, together with the tradition of the revolutionary woman, were transferred to the Jewish youth organizations during the Holocaust.

Female Leaders in the Ghetto

The Jewish youth movements continued most of their unique activities during the first period of World War II (1939–1942). They appear to have been strong and effective, better adapted to the new reality of the ghettos than adult organizations. In some of the ghettos, their overall activity flourished, sometimes even exceeding that of the pre-war period.

The role of women in this activity was significant from the very first days of the war and the German occupation. Just before the war some movements (Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir and Dror-Freiheit) established an alternative leadership (Hanhagah Bet), comprised mostly of women, in case the male leaders were conscripted to the Polish army. Although these alternative leaderships functioned only partially in the first chaotic months of the occupation, the promotion of women into leading roles soon became evident. The first delegates to the German-occupied area of Poland (from Vilna and Russian-occupied Poland) were women: Frumka Plotniczki, Zivia Lubetkin (Dror-Freiheit, Warsaw) and Tosia Altman (Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Warsaw).

During this period (1940–1942) many branches of the youth movements were led by women, or included women or girls in the local and the central leadership. Indeed, not a single ghetto leadership lacked at least one influential woman.

The ongoing occupation and the ghettos necessitated the creation of a new functionary: an emissary or delegate (shelihah/shaliah – also referred to as kashariyot) of the central leadership. This role was filled mainly by females because of the danger of the “circumcision test” at German checkpoints. However, the delegates of the central movement who traveled illegally from ghetto to ghetto were not mere mail carriers delivering messages and underground press from Warsaw to the provinces. They had to remain at their destination for several days or weeks in order to discuss ideological and educational matters with the local leadership, oversee local educational activity, plan and lead theoretical seminars for the older members of the branch, etc. In short, they had to personally represent the central leadership, its ideas, programs and operations. The shelihah functioned much more like a high-ranking staff officer in a military organization than as an underground courier. Four major shelihot were Frumka Plotniczki, Gusta Dawidson (Akiva, Cracow), Tosia Altman and Haika Grosman (Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Bialystok), all of whom were in leading positions in their movements and acted as authorized representatives of the central leadership.

Women & Fighting Organizations

When it came to fighting, it appears that the new leadership of women was somewhat reduced: they left the combat to the men and were relegated to auxiliary duties such as communication, logistics, first aid, documentation, etc. However, although there was some change in gender status during the days of the armed underground and the fighting (1942–1944), women’s role and status remained significant.

Although men occupied most of the command positions (for example, none of the twenty-two Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa (Jewish Fighting Organization, ZOB) units that participated in the Warsaw uprising was led by a woman), in several cases women did serve as commanders. Rozka Korczak (Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Vilna) was the commander of an important position in the Vilna Ghetto; Vitka Kempner-Kovner (Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Vilna) led small units on railway sabotage operations in the Vilna Ghetto and the forests; and Zivia Lubtekin led the escape through the sewers from the burning Warsaw Ghetto. In many of the underground fighting units, there were women as courageous and daring as the men, and sometimes even more so: Zelda Treger the partisan from Vilna, Frumka Plotniczki in Bedzin, Haika Grosman in Bialystok, Rivka Glanz in Chestochowa. Furthermore, women leaders continued in some important functions from the earlier period. Now more than ever the fighting organizations needed them as delegate-couriers to deliver arms and military instructions from ghetto to ghetto. Young women such as Hella Schüpper-Rufeisen (Warsaw–Cracow), Ina Gelberd (Bedzin–Zawiercie), Fredka Oxenhendler (Sosnowiec–Cracow) and many other delegate-couriers traveled with forged documents, revolvers, ammunition and instructions hidden in their clothing. These girls had not previously belonged to the leadership, but their courage and the importance of their missions made them equal partners with their leaders.

Because of their moral and ideological authority women also proved vital during the days of preparations for the final battles. In several cases, the women were more firm and determined in crisis situations. They were constant in their adherence to the idea of Jewish resistance, morally supporting the fighters, mourning the dead and encouraging their male partners. For many of their comrades they symbolized the spirit of the Jewish uprising. In their words and behavior they combined the biblical prophet Deborah with the modern revolutionaries, Rosa Luxemburg and La Pasionaria.

Dual Leadership

Perhaps the most interesting characteristic of women leaders in the Jewish underground during the preparations and the battles was their indispensable role in what one may call the “dual leadership.” This was a unique model of leadership, which for reasons of “unity of command” is usually hierarchic, with only one leader at each level of any given social organization. Nevertheless, in some historical cases—for example, the Prussian-German army (1860–1918) and the Red Army (1918–1942)—there have been two leaders within a single level of a military organization. In the first case, the German commander and his chief of staff shared the military responsibility according to short-term and long-term parameters. In the second, the Red Army commander had the military responsibility while his political officer (commissar) had the moral-ideological responsibility. However, in both cases the division of functions was not wholly rigid and the capacity of the two leaders to act in accord was heavily dependent on their mutual understanding.

A comparable “dual leadership,” composed of one man and one woman, emerged in many of the Jewish undergrounds in the ghettos. The main reason for this development lay in the family structure of the intimate group in which the male and female youth leaders were viewed by the youngsters as the group’s “father” and “mother.” During the war, there was an additional reason: romance.

The leaders of the youth movements during the war were young people in their twenties. Under normal circumstances they were supposed to immigrate to The Land of IsraelErez Israel and establish A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim; most of them were also planning to marry and raise families. But immigration was postponed because of the war and they were confined in the ghettos, occupied with their new missions. They simply needed to love and be loved—and the persons most available and attractive to them were their comrades of the opposite sex in the youth movement leadership.

Love affairs between the youth movement leaders were quite common in the Polish ghettos. The most famous were Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin; Gusta Dawidson and Shimshon Draenger; Haika Grosman and Adek Buraks; Vitka Kempner and Abba Kovner; and Chajka Klinger and David Kozlowski (Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Bedzin). These couples supported each other on both the collective and personal levels, frequently sharing responsibilities during the days of the underground. Although the man was usually considered to be the representative leader, in practice the woman sometimes became the actual leader. Though there was no clear distribution of power and responsibility between the two; it seems that the woman typically had more “emotional” functions (which are very important in underground activity) while the man was considered more “rational.” He used weapons and dealt in combat while she used words and provided moral support.

In other cases, the women were considered more as the “leader’s girl” than as leaders per se. This was true of Tema Sznajdermann and Mordechai Tenenbaum-Tamaroff (Dror-Freiheit, Bialystok); Mira Fucherer and Mordechai Anielewicz (Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Warsaw); Fredka Oxenhendler and Juzek (Azriel) Korzuch (Ha-Noar ha-Zioni, Sosnowiec); and Hella Schüpper-Rufeisen and Lotek Graubard (Akiva, Warsaw). However, even these women were not passive assistants to their beloveds but rather their equal partners in special missions and their paramount supporters in dark times.

There was also dual leadership without a love relationship: Hershel Springer and Frumka Plotniczki together led Dror in Bedzin without being lovers but with considerable mutual understanding. Sometimes a single woman became a leader among the surrounding men, as did Mire Gola in Cracow, Tosia Altman and Rivka Glanz.

In some of the dual leaderships the woman and the man both perished. In one case, that of Gusta Dawidson and Shimshon Draenger (1943), this was the fulfillment of a secret contract between the two: she surrendered to the Germans when she heard that Shimshon had been captured. In two cases—Antek Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin and Abba Kovner and Vitka Kempner—both parties survived to lead a happy life in Israel. In most cases only the women survived; in their memoirs they focused on the story of their dead comrades. The initial historiography of the Jewish uprising was thus written by women who tended to minimize their own role in the events and emphasize their partner. The later historiography was written by men and again the role of the women was reduced. It seems that the time has come to give these women their due.

Draenger, Gusta Davison. Justyna’s Narrative. Edited by David H. Hirsch and Eli Pfefferkorn. Translated by Roslyn Hirsch and David H. Hirsch. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996

Grosman, Haika. The Underground Army: Fighters of the Bialystock Ghetto (translated from the Hebrew by Shmuel Beeri). New York: Holocaust Library, 1987

Klinger, Chajka. A Diary from the Ghetto (Hebrew). Kibbutz Ha-Ogen: N.p., 1959

Korczak, Rozka. Flames in the Ashes (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: N.p., 1949, 1965

Lubetkin, Zivia. In the Days of Destruction and Revolt (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 1981

Mazia, Fredka Oxenhendler. Friends in the Storm(Hebrew). Jerusalem: N.p., 1964

Tenenbaum, Mordechai. Pages from the Flames (Hebrew), second edition. Beit Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: Hakibbutz Hameukhad, 1986

Ronen, Avihu and Yehoyakim Cochavi, eds. Third Person, Singular: Biographies of Youth Movements’ Activists during the Holocaust (Hebrew) 2 volumes. Tel Aviv: N.p., 1995