Feminist Theology

Like Jewish religiosity as a whole, Jewish feminism is praxis-oriented. Its goal is to move Jewish religious law, history, practice, and communal institutions in the direction of the full inclusion of women. Thus, feminist theological reflection is often embedded in ritual and liturgy, fiction and historical research, textual interpretation and midrash. Jewish feminist theology focuses on central Jewish categories, themes, and modes of expression: the nature of God and the status of God-language, the nature and scope of Torah, the status of halakhah and the dynamics of halakhic change, the centrality of hierarchy to Jewish religious thinking, and the authority of Jewish tradition and of women’s experience. Modern feminist theologians raise questions and theorize about the nuances of these categories.

Because theology is not a central mode of Jewish religious expression, there is not a great deal of formal feminist theology within Judaism. Like Jewish religiosity as a whole, Jewish feminism is praxis-oriented. Its goal is to move Jewish religious law, history, practice, and communal institutions in the direction of the full inclusion of women. Thus feminist theological reflection is often embedded in ritual and liturgy, fiction and historical research, textual interpretation and A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash. This said, however, it is possible to identify distinctive theological strands within Jewish feminism. Jewish feminist theology focuses on central Jewish categories, themes, and modes of expression—for example, God, prayer, Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, and halakhah—and asks who created them and whose interests they reflect. It raises meta-questions about Jewish tradition. Rather than seeking to revise particular The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhot, for instance, it explores The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah as a category from a feminist perspective. Or, in addition to changing individual prayers, it considers the broad question of the language of prayer and how that language affects women and reflects or fails to reflect their experience.

Theological Themes

One way of approaching Jewish feminist theology is through its major themes. A number of important theological issues emerge within Jewish feminist work: the nature of God and the status of God-language, the nature and scope of Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, the status of halakhah and the dynamics of halakhic change, the centrality of hierarchy to Jewish religious thinking, and the authority of Jewish tradition and of women’s experience. While these issues are implicit in non-theoretical modes of feminist expression, they have also received direct theoretical attention.

Nature of God and Status of God-language

The first theological topic to be addressed by Jewish feminists was the centrality of male imagery for God in Jewish tradition. The problem of male language has been a central feminist concern from the mid-1970s and has been explored both in explicitly theological work and through liturgical innovation. In an article first published in 1979 but circulating earlier, Rita Gross argued that Jewish failure to develop female imagery for God is the ultimate symbol of the degradation of Jewish women. She maintains that because exclusively male language for God reflects and reinforces a male-centered definition of humanity, women would be fully included in the Jewish covenant community only were God also addressed as “God-She.” Gross’s insistence that “the familiar ha-kadosh barukh hu (‘the Holy One, blessed be He’) is also ha-k’dosha berukha he (‘the Holy One, blessed be She’) and always has been” (1979, 173), was given early liturgical expression by Naomi Janowitz and Maggie Wenig. In 1976, as undergraduates at Brown University, they wrote an English-language Sabbath prayer book that referred to God throughout using female pronouns and imagery.

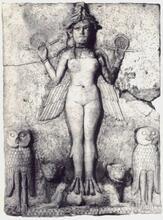

Since the 1970s, feminist reflections on and experiments with God-language have broadened and deepened. Feminist thinkers such as Judith Plaskow, Marcia Falk, and Rachel Adler have developed both a more detailed critique of traditional images for God and a fuller understanding of the theological questions surrounding new, alternative imagery. Plaskow’s Jewish feminist theology Standing Again at Sinai contains a substantial discussion of the problems with picturing God as male and thinking of “him” as outside the world and above it. Adler, in Engendering Judaism, considers the nature and function of metaphorical language and explores such questions as whether personality should be attributed to God and how God’s power should be imagined. Feminist liturgical innovations have also matured. Experiments with female language have evolved into more fundamental changes in the ways that God is conceived, and alterations in the English translations of prayers have been combined with changes in the original Hebrew. Liturgist-theologians such as Lynn Gottlieb have called on God using a myriad of metaphors. They have borrowed traditional Hebrew images like Shekhinah, the feminine aspect of God in Jewish mysticism; drawn on imagery from other religious traditions; and looked for or created Hebrew names with feminine resonances, like Rahmana, mother of wombs, or rakhmaniah, compassionate giver of life. These two lines of experimentation—with new images and new Hebrew—come together most fully in the work of Marcia Falk, whose The Book of Blessings entirely reworks the daily, Sabbath, and Rosh Hodesh liturgies from a feminist perspective. Falk’s new prayers also represent the most complete expression of another tendency evident in many feminist images of God: a focus on God’s immanent presence within the world rather than on God’s distance and transcendence.

Nature and Scope of Torah

Just as new feminist conceptions of God have emerged from both formal theology and other genres, the same is true of new conceptions of Torah. Torah as the central symbol and complex content of Jewish religious reflection is, like Jewish images of God, profoundly male-centered. Jewish canonical texts were written by men for a male audience, and until the contemporary era the centuries-long conversation interpreting these texts took place entirely among men. This led many Jewish feminists to perceive Torah as partial and incomplete. Only a portion of the Jewish encounter with God has been passed down through the generations, and feminists must now attempt to recover women’s voices within the tradition and to reconstruct the contours of women’s religious experiences.

This task of reconstruction has many dimensions. Judith Plaskow has emphasized the historiographical aspect of broadening Jewish memory. Reading canonical and noncanonical sources with new questions and from a new angle of vision, she claims, feminists can find evidence of women’s religious leadership, of changing patterns of family and gender relations, and of women’s spiritual lives within and outside of mainstream religious institutions. This evidence makes clear that “Judaism” has always been more complex and diverse than official versions of Jewish history allow. Taken seriously, it provides Jews with a richer and fuller history on the basis of which they can construct contemporary Jewish identities. Other feminists have envisioned the project of discovering women’s Torah as part of a process of continuing revelation. As Ellen Umansky has argued, women, in interaction with both traditional sources and one another, must be open to “receiving” new understandings of themselves and of Jewish practices, concepts, and stories. Many Jewish feminists have written new midrash on biblical texts, highlighting hitherto unexplored aspects of the feeling and perceptions of biblical women. Umansky, in sharing a midrash on the binding of Isaac that came to her during a women’s Rosh Hodesh ritual, places the creation of new midrash in a theological context by describing it as an unconscious, visionary response to elements of Jewish tradition. Rachel Adler stresses the importance of audience to new understandings of Torah. As women enter the circle of Jewish interpretation, responding to narratives authored by men, they are able to hear not only what central Jewish stories include but also what they omit and conceal. The judgment and laughter that arise from the tensions between the storytellers’ intent and the perceptions of a new feminist audience are gifts of feminist Torah that may enable Jews to confront the absurdity as well the damage of misogyny and to restore traditional texts as part of a “trajectory toward holiness” (1998, 2).

Status of Halakhah and the Dynamics of Halakhic Change

The important point theologically about these different modes of reclaiming women’s history is that Jewish feminists are defining as Torah the insights emerging from diverse avenues of exploration. Thus, the stories of Genesis are traditionally read and interpreted are Torah, but so is the new historical information to be gleaned from them, and so are the same stories read through a feminist lens and elaborated through feminist midrash or fiction, art, or dance. Torah in its traditional sense is decentered. It is placed in a larger context in which the experience of the whole Jewish people becomes a basis for legal decision-making and for spiritual and theological reflection.

One area within the larger category of Torah that is particularly challenging for feminists is the issue of Jewish law. Because halakhah is central to Jewish practice and self-definition, and because the development and transmission of halakhah has been the preserve of a male elite, halakhah raises numerous difficult problems. As a practical matter, women’s halakhic disabilities, such as their exclusion from a The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyan or inability to initiate divorce, were the earliest focus of Jewish feminists, leading them to question and then to try to change Jewish tradition. Halakhic issues remain central for Orthodox feminists, who seek not only halakhic remedies for particular problems but also access to halakhic learning so as to participate in the processes of communal decision-making. Beyond this, on the theological level, feminists have explored the presuppositions of the halakhic system, reflecting on the nature of halakhah and its place in a feminist Judaism. As Judith Plaskow asked in an early article, if halakhah is part of the Jewish system that women had no hand in creating, then “how can we presume that if women add their voices to the tradition, halakhah will be our medium of expression and repair?” (1983, 231).

Plaskow is ambivalent about halakhah, leaving open the issue of its ultimate compatibility with feminism. She wonders whether a system based on law can be harmonized with a feminist emphasis on relationship and whether the rigidity and abstractness of the traditional halakhic system does not foster a certain distance from the concrete world of people and things. She argues that a feminist halakhah would look very different from halakhah as it has been historically constituted, not just in its specifics, but also in its fundamental presuppositions about the origins and authority of the law.

Rachel Adler, who in Engendering Judaism offers the fullest feminist theological exploration of halakhah, agrees that a feminist halakhah is a transformed halakhah, but she sees the law “as a way for communities of Jews to generate and embody their Jewish moral visions” (1998, 21). Drawing on the work of legal theorist Robert Cover, she argues that Jewish feminists dare not neglect the task of transforming halakhah, because law is a “bridge” between the present religious and moral worlds that Jews inhabit and the “richer and more vital worlds that could be” (35). Adler does not believe that a new halakhah can be generated simply through more enlightened application of the current system, because large numbers of questions about how women might function as autonomous religious agents lie completely outside the realm and imagination of Jewish law. Rather, she calls for a new moment of “jurisgenesis,” of creativity and revitalization, in which Jewish communities create “a universe of meaning out of a shared body of precepts and narratives” and commit themselves to the ongoing processes of interpretation and renewal (34).

For the most part, it is non-Orthodox feminists who have engaged questions of law on a theological level, while Orthodox feminist treatments of halakhah focus mainly on specific legal issues of particular concern to women. Tamar Ross is the one Orthodox feminist who addresses the theological challenges posed by a feminist critique of halakhah. She argues that concrete efforts to alter the legal position of women in Jewish law cannot be divorced from more far-reaching consideration of the status of halakhah and the question of the extent to which halakhic change is possible. Because women’s status in halakhah is a moral issue and not simply a practical one, Orthodox Jews need a theology that will allow them to acknowledge that Torah and halakhah are shaped by culture, and yet still to see them as representing the eternal voice of God. Ross tries to develop an account of halakhah that allows for change in the direction of greater inclusion of women, but she sees that change as part of the unfolding of divine revelation.

Centrality of Hierarchy

Another area in which Torah raises difficult problems for feminists is in its tendency to associate particular groups of people with oppositional categories such as spiritual/material or sacred/profane. Drorah Setel has argued that the central tension between Judaism and feminism does not lie in the fact of Torah being a male-centered text, focusing on male activities and defining men as the normative human beings, but in the underlying Jewish understanding of holiness as separation. In contrast to feminism, which places a profound value on relationship, Judaism has emphasized separation, defining the holy as that which is “set apart” from ordinary or mundane things. The hierarchical difference between men and women is but one important instance of oppositional and hierarchical modes of thinking within Jewish tradition. To be a holy people is both to reject the beliefs and behaviors of surrounding nations and to make internal separations between pure and impure, Sabbath and week, priests and ordinary Jews, and men and women.

In response to this critique, feminists have sought to think about Jewish identity, belief, and practice in ways that are not invidious or hierarchical. They have reflected on what it means to fully include women and women’s differences in the Jewish community. Genuine equality is not to be understood in terms of women’s achieving some taken-for-granted male standard but in terms of full recognition of the diversity of the Jewish community, and of women’s differences both from men and from each other. Feminists have reworked rituals that seem to sanctify hierarchy in order to affirm both separation and connection. While the Lit. "distinction, division." The blessing recited at the close of the Sabbath and Festivals to indicate the distinction between holy and ordinary days.Havdalah ceremony that separates the Sabbath from the week, for example, distinguishes holiness, light, Israel, and the Sabbath on the one side from commonness, darkness, other peoples, and the week on the other, Marcia Falk has rewritten the last blessing of the ritual so as to hallow both sides of the distinction. In a more theoretical vein, Judith Plaskow tries to rethink the notion of chosenness, using a part/whole model to express the relationship between Israel and other nations. She offers the term “distinctness” in lieu of the concept of chosenness, in order to point to the larger (human and cosmic) unity to which Jews and other peoples belong, as well as to the importance of all the individual groups that make up that unity.

Authority of Jewish Tradition and of Women’s Experience

Underlying all these areas of innovation is the central theological issue of authority. In questioning traditional conceptions of God or Torah, in agitating for halakhic change, in creating new liturgies and other forms of Jewish expression, feminists take the power both to criticize ancient traditions and to develop new forms that they hope will be part of the Judaism of the future. What gives them the right to question a religious tradition that claims a divine origin and that, at the minimum, represents the accumulated wisdom of centuries? What makes new images of God or other new feminist forms Jewish? Are there any a priori restraints on feminists in terms of claiming the Jewishness of particular innovations? What assumptions about the origins and authority of tradition lie behind feminist reconstructions?

While much feminist work simply presupposes that Jewish tradition has been constructed by men and can be deconstructed and reconstructed by women, several feminist thinkers have self-consciously reflected on issues of authority and method. Ellen Umansky argues that Jewish feminist theology must be a responsive theology that “emerges out of an encounter with ‘images and narratives from the Jewish past’ and from the experiences of the theologian” (194). Rather than defining in advance what is authentically Jewish, this theology should allow for dialogue between the sources and fundamental categories of tradition and the theologian’s subjective responses.

Judith Plaskow also affirms the importance of grappling with the materials of tradition, but she sees the notion of “women’s experience” as a disruptive principle that feminists bring to Judaism from the outside. The insistence that women are full Jews and full persons is an insight that comes from contemporary feminism and that necessarily challenges many of the assumptions of a tradition in which men are the normative Jews and normative human beings. In beginning with the assumption of women’s full humanity, feminists finally root themselves not in Jewish texts but in Jewish communities struggling for greater justice and inclusiveness and for the transformation of tradition.

Rachel Adler rejects any dichotomy between “women’s experience” and “authentic Judaism,” focusing on praxis as the place where these categories meet. Jewish feminism has focused on practical concerns, she says, because “because law, ritual, and study are the constitutive activities of Judaism.” Women need to become full participants in these activities, at the same time criticizing and transforming androcentric structures and texts. A Jewish feminist method must “mirror the fluid boundaries that exist among theology, halakhah and ethics, liturgy, and textual exegesis,” drawing on the materials of tradition and at the same time challenging gender injustice (1998, xix, xxii-xxiii).

Tamar Ross, focusing on the issue of authority as it emerges in the halakhic context, affirms both the flexibility of halakhah and its absolute nature, arguing for a gradualist approach to halakhic change. Because there is an inner logic to tradition that cannot be tampered with casually or wholesale, women need to find creative new ways to live within a halakhic framework, trusting that some of their solutions to what appear to be halakhic injustices “will eventually become institutionalized and recognized as…genuine factor[s] in halakhic deliberation” (1993, 489f).

Theologians

As the regular reappearance of certain names in the above discussion suggests, it is possible to approach Jewish feminist theology through discussing the small number of women doing work in the field, as well as through exploring certain themes. Two thinkers whose work provides an excellent illustration of the close relationship between theory and practice in Jewish feminist theology are Lynn Gottlieb and Marcia Falk. Gottlieb is a rabbi and performance artist, leader of Congregation Nahalat Shalom in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who has been creating feminist midrash and ritual for many years. Her book, She Who Dwells Within: A Feminist Vision of a Renewed Judaism, describes her earlier work and provides it with a theological foundation. “She who dwells within” refers to the Shekhinah, the indwelling feminine presence of God in Jewish mysticism. The Shekhinah image is central to Gottlieb’s theology, but she does not limit her understanding of Shekhinah to the repertory of images available in the tradition. Drawing boldly on Canaanite and Native American literatures, she invokes Shekhinah using a flood of metaphors: Birdwoman, Dragonlady, Queen of Heaven, Tree of Life, invisible web, and many others. Women’s stories, ceremonies, and acts of social justice, which Gottlieb discusses in successive sections of her book, are ways of connecting with and coming home to Shekhinah and living responsibly in acknowledgement of her presence. In telling women’s stories as if they were central, rather than peripheral, to the biblical narrative, feminists recover and invent “Torat Ha-Shekhinah” [sic], a sacred narrative of women’s lives that gives new meaning to Torah. Ceremonies such as the creation of a Mishkan or portable shrine, the celebration of the new moon, and the marking of various passages in women’s lives create a dwelling place for the Shekhinah and allow women to recognize and appreciate the ways in which Shekhinah dwells within them. Learning to respect the body of the earth through developing a system of eco- The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut, and pursuing justice and nonviolence in every area of life, are ways of honoring both the Shekhinah and the interrelatedness of all beings that are part of the divine unity.

Marcia Falk, a poet, liturgist, and artist who lives in Berkeley, California, is the author of a prayer book that is simultaneously a work of feminist theology. Not only do the many prayers found in The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath, and the New Moon Festival convey a coherent religious vision, but the book also contains an extended commentary on the author’s liturgical choices in which Falk explicitly discusses the theology in which her prayers are grounded. Unlike most other feminist theologians and liturgists, Falk is not interested in replacing images of God as Lord and king with female metaphors, even as one dimension of liturgical language. She questions the need to address God as a “you,” either male or female, imagining God instead as “an awareness, or a sensing, of the dynamic, alive, and unifying wholeness within creation” (419). Many of her prayers use natural or nonpersonal images of God that seek to dislodge what she sees as the pernicious anthropocentrism or “species-ism” of the traditional prayer book. Other prayers refer to God only indirectly, locating divinity in certain experiences of the world rather than any explicit invocation of the sacred. Unlike Gottlieb, who refers to the Shekhinah as “she who dwells within” but clothes her in many vivid images, Falk abjures any image of God that suggests that God is separate from a unifying wholeness.

In evoking the divine as entirely immanent in creation, Falk does not offer just one substitute for the traditional formula “Blessed are you, YHVH our God,” but rather experiments with many new blessing forms. She explains that she is troubled not simply by the patriarchal nature of the traditional invocation, which seems to make an idol out of maleness, but by any strictly formulaic language. All immutable forms, she argues, are potentially idolatrous in that they absolutize particular images, seeming to revere them rather than what they signify. Falk’s insistence on the need for continual liturgical innovation accords with her understanding of monotheism as “honoring the diversity within the unity of creation” (432). As she sees it, authentic monotheism is not “a singularity of image but an embracing unity of a multiplicity of images” (1987, 41).

Judith Plaskow’s Standing Again at Sinai: Judaism from a Feminist Perspective and Rachel Adler’s Engendering Judaism: An Inclusive Theology and Ethics are the only two full-length Jewish feminist works to focus entirely on theology. Plaskow, a professor of Religious Studies at Manhattan College, structures the core of her book around the central Jewish categories of Torah, Israel, and God. What would these crucial concepts look like, she asks, were women full participants in their formulation? Plaskow argues that, since Jewish tradition as it has been handed down through the generations is the product of a male elite, placing women at the center of Jewish life alongside men would necessarily mean reworking many aspects of tradition. Rethinking Jewish theology is crucial to Jewish feminism, because women’s concrete disabilities are rooted in theological assumptions about human and divine nature that have a pervasive influence in Jewish life. Torah, for example, records the experiences of encounter with God of only part of the Jewish people, rendering invisible women’s efforts to make meaning in response to the central events of Jewish history. Defining Torah as Jewish memory as it continues to be active in and shape the present, Plaskow calls for a Torah/memory that lifts up the experiences and deeds of women erased in traditional sources. “The central events of the Jewish past,” she says, “are not simply history but living, active memory that continues to shape Jewish identity and self-understanding” (29). Jewish feminists cannot reshape Judaism in the present without reclaiming their history, because it is in telling the stories of the past that Jews learn who they are today.

Expanding Torah also entails rethinking the identity of the community of Israel, because Torah as male memory is the logical counterpart of an understanding of Israel in which men are the normative Jews. Feminists must insist on the full inclusion of women in every aspect of Jewish life, not simply as individuals but as a class that has, until now, been constructed as Other. This means grappling with the issue of the role of difference in community and asking what it means to create a pluralistic community in which there is room for many sorts of differences. Because a community’s values are also expressed and legitimated by the ways in which it thinks about God, the reconstruction of Torah and Israel is bound up with reimaging the divine. On the one hand, images of God as male serve to sanctify and naturalize the marginalization of women in Torah and community. On the other, the fuller participation of women in Jewish religious life has been accompanied by a burst of new names for God that witness to and support women’s presence in community. Plaskow discusses a wide range of new feminist imagery for God, including personal images, some of them female; natural images, and nonpersonal and conceptual images. All of these capture important dimensions of an inclusive monotheism, she argues, and need to be explored and developed.

Rachel Adler, who teaches Modern Jewish thought and Judaism and Gender at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles, argues that Torah, God, and Israel are not sufficient categories for a feminist Judaism. In her view, the fact that Plaskow devotes the last two chapters of Standing Again at Sinai to issues of sexuality and Jewish feminist activism suggests that feminists need to move outside traditional categories in their reconstruction of Judaism. Adler playfully suggests that the “shit” method, from the Yiddish “throw”—as Eastern European grandmothers were said to “throw” a little of this and a little of that into their cooking—is an appropriate image for a feminist methodology. In a context in which halakhah and Jewish historical and textual traditions all privilege men and downplay the roles of women, feminists must be able to experiment with a variety of approaches to Jewish sources and combine these approaches in fresh and imaginative ways. Adler presents her theology through a close but multidisciplinary reading of particular Jewish texts, because she believes that God becomes present in the midst of community through the conversation between traditional texts and the lived experiences of religious communities.

Adler’s chapter on law, for example, begins with a Yiddish folktale about women’s dissatisfactions with halakhah and ends with a feminist reading of two rabbinic stories about Rabbi Nahman’s wife Yalta that touch on legal issues affecting women. Her discussion of these texts frames a more theoretical analysis of the problems with traditional and liberal halakhic methodologies and the possibilities of creating a feminist halakhah. The image of law as a bridge, mentioned above, allows her to insist on the importance of halakhah as the way in which Jews embody and live out Jewish values, without identifying halakhah with a particular set of texts and their interpretations within Orthodoxy. Adler’s chapter on worship asks what it means to include women in Jewish prayer. Less text-centered than other sections of her book, it addresses problems of inclusion ranging from the contradictions of an egalitarianism that welcomes women as participants in prayer while ignoring their distinctive concerns, to the creation of women’s prayers, to issues of God-language and imagery. In contrast to the chapter on prayer, Adler develops an ethic of sexuality and relationship through close engagement with a series of pivotal biblical texts, including the creation accounts of Genesis, Leviticus 18, the Song of Songs, and the book of Ruth. Drawing on the insights of psychology, literary criticism and other fields as called for by her “shit” method, she seeks to reclaim the holiness of difficult sources without denying their patriarchal nature. She critiques the ethic of domination that pervades many texts on sexuality and still finds in them trajectories toward mutuality and intersubjectivity. Adler’s conviction that praxis is central to a feminist Judaism shapes the final chapter of Engendering Judaism, which seeks to transform the traditional wedding ceremony into a marriage between two subjects. Her interest in textual analysis and her theoretical arguments concerning law, worship, and sexuality are all brought together in a concrete proposal for altering the contractual nature of marriage so that it genuinely reflects the vision of redemptive union found in the seven marriage blessings.

It is not surprising that almost all the Jewish feminists who do theological work are non-Orthodox. Not only does their writing profoundly challenge traditional understandings of authority, but it also explores and extends problems of authority, law, God, and human selfhood that are central to liberal Judaism. Tamar Ross, who teaches philosophy at Bar Ilan University and Jewish Thought at Midreshet Lindenbaum Women’s Yeshiva near Jerusalem, is an important exception to this generalization, in that she is an Orthodox feminist who finds it essential to address the theological challenges that underlie agitation for halakhic change. Ross cut an exceptional figure at the three international conferences on Feminism and Orthodoxy held in New York between 1997 and 2000, in that, while the programs of all three conferences focused on particular halakhic and personal issues, she chose to speak about theology. Halakhic observance, she noted at the first conference, rests on certain theological premises that seem to be threatened by feminism, chief among them the notion of Torah as God’s word. Feminist criticisms of the male bias of Jewish tradition and of its patriarchal and hierarchical character seem to suggest that Torah is simply the projection of male wishes and of a patriarchal social system. In response to this challenge, Ross develops an account of revelation through history that draws on certain strands in The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah and on the thought of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook. “God’s Torah is by definition eternal, perfect and all encompassing,” she said, but all receptions of God’s word “are time- and culture-bound,” conditioned by social and historical circumstances and by the capacity of particular Jewish communities to hear and understand the meanings of revelation. Such time-bound conditions are not themselves accidents of history, however, but “continuing reverberations of God’s eternal word” (2000: 26). This perspective allows Ross to view patriarchy as a stage in Jewish history that had its own importance and logic and yet entertain the idea that certain forms of feminism also represent a further, and morally more refined, understanding of God’s word. It allows her to affirm Torah as “from heaven” and still make room for halakhic change.

The feminist scholars discussed here, who explicitly address theological issues, represent only the most self-conscious strand in a more far-reaching feminist theological discourse. Insofar as all Jewish feminist efforts at change necessarily make certain assumptions about the authority of tradition and the nature of self, God, and community, they engage theological questions on many different levels.

Adler, Rachel. Engendering Judaism: An Inclusive Theology and Ethics. Philadelphia and Jerusalem: 1998

Adler, Rachel. “‘I’ve Had Nothing Yet, So I Can’t Take More.’” Moment 8 (September 1983): 22–26; Falk, Marcia. The Book of Blessings: New Jewish Prayers for Daily Life, the Sabbath and the New Moon Festival. San Francisco: 1996

Falk, Marcia. “Notes on Composing New Blessings: Toward a Feminist-Jewish Reconstruction of Prayer.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 3 (Spring 1987): 39–53

Falk, Marcia. “Response to Feminist Reflections on Separation and Unity in Jewish Theology.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 2 (Spring 1986): 121–125

Gottlieb, Lynn. She Who Dwells Within: A Feminist Vision of a Renewed Judaism. San Francisco: 1995

Gross, Rita. “Female God Language in a Jewish Context.” In Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, edited by Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow, 167–173. San Francisco: 1979

Gross, Rita. “Steps Toward Feminine Imagery of Deity in Jewish Theology.” In On Being a Jewish Feminist: A Reader, edited by Susannah Heschel, 243–247. New York: 1983

Janowitz, Naomi and Maggie Wenig. Siddur Nashim: A Sabbath Prayer Book for Women. Privately circulated, 1976. Selections are reprinted as “Sabbath Prayers for Women.” In Womanspirit Rising: A Feminist Reader in Religion, edited by Carol P. Christ and Judith Plaskow, 174–178. San Francisco: 1979

Plaskow, Judith. “Jewish Theology in Feminist Perspective.” In Feminist Perspectives on Jewish Studies, edited by Lynn Davidman and Shelly Tenenbaum, 62–84. New Haven and London: 1994

Plaskow, Judith. “The Right Question is Theological.” In On Being a Jewish Feminist: A Reader, edited by Susannah Heschel, 223–233. New York: 1983

Plaskow, Judith. Standing Again at Sinai: Judaism from a Feminist Perspective. San Francisco: 1990

Ross, Tamar. “Can the Demand for Change in the Status of Women Be Halakhically Legitimated?” Judaism 42 (Fall 1993): 478–492

Ross, Tamar. “Modern Orthodoxy and the Challenge of Feminism.” In Jews and Gender: The Challenge to Hierarchy, edited by Jonathan Frankel, 3–38. Oxford: 2000

Setel, T. Drorah. “Feminist Reflections on Separation and Unity in Jewish Theology.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 2 (Spring 1986): 113–118

Umansky, Ellen. “Creating a Jewish Feminist Theology: Possibilities and Problems.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 187–198. San Francisco: 1989

Umansky, Ellen. “(Re)Imaging the Divine.” Response 41–42 (Fall-Winter 1982): 110–119.