Lucy Fox Robins Lang

Lucy Fox Robins Lang contributed greatly to both the labor movement and the anarchist movement as aide and confidante to major figures like Emma Goldman and Samuel Gompers. A confirmed anarchist from age fifteen, Lang married anarchist Bob Robins in 1904. Lang and Robins travelled in a mobile home for ten years, organizing activists around the country. Lang eventually met Emma Goldman and began arranging speaking tours, bail money, and publicity for the famed activist. She also worked closely with labor leader Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), becoming one of the few women to speak at the AFL annual convention. Lang also led several successful activist organizations herself, including a group advocating to free political prisoners of World War I.

A committed anarchist by age fifteen, Lucy Fox Robins Lang participated actively in the labor and free speech movements of early twentieth-century America. She directed regional and national committees in support of persecuted anarchists, antiwar activists, and labor organizers, while earning her livelihood as a printer, waitress, vegetarian restaurant owner, and real estate broker. Eventually, she moved into the mainstream of the labor movement, becoming an adviser to and confidante of Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Although her focus shifted, the impulse behind Lang’s work remained constant. She credited her activism to the legacy of her paternal grandfather, Reb Chaim “the Hospitable,” who helped members of the Jewish community in Kiev, Russia, deal with personal difficulties and conflicts with the authorities.

Chicago and New York: marriage and early activist work

The eldest child of Moshe and Surtze Broche Fox, Lucy was born on March 30, 1884, in Kiev, Russia. She grew up in the nearby town of Korostyshev, in a household and a community governed by Jewish tradition. Her family immigrated to the United States when Lucy was nine, settling briefly in New York’s Lower East Side and then in Chicago with relatives. A silversmith by trade, Moshe Fox found work applying gold leaf to picture frames. Lucy worked in a cigar factory and, as the eldest child, helped to care for her sister and three brothers. At night, she took English and citizenship courses at Chicago’s Hull House, a settlement house.

When Hull House founder Jane Addams asked Lucy to assist a dancing instructor, a crisis erupted in the family. She asked Jane Addams to visit her home to persuade her parents to allow her to participate in the interreligious and coeducational dance class. Lucy was dazzled by what she called Addams’s “bright vision of freedom” and soon moved on to even more daring ventures.

Late nineteenth-century Chicago seethed with left-wing political activities, and Lucy was drawn to the most radical group, the anarchists. She began attending lectures, reading political literature, and participating in meetings and demonstrations. Never an advocate of anarchism’s direct-action wing, she favored practical and results-oriented political activism to achieve anarchism’s aim of maximum freedom for every individual. While still a teenager, she met fellow anarchist Bob Robins and married him in 1904. Adopting the anarchist view that love alone should govern a marriage, Lucy insisted that they sign a legal document limiting the union to five years, allowing her to continue her political activities, requiring the sharing of all household tasks, and stipulating that there would be no children. The couple did separate as specified by their contract, but soon reunited and remained married for twenty years.

The couple moved to New York City, where Lucy met Emma Goldman and was drawn to her interpretation of anarchism. Goldman’s emphasis on the contributions that women could make to social and political causes and her ability to function outside the confines of the immigrant community appealed to Lucy. She began to provide various anonymous and unpaid services to the frequently arrested Goldman and to many other well-known political activists. She arranged speaking tours, rented halls, raised bail money, and directed defense committees to raise public awareness of the activists’ beliefs. Due in part to her efforts, two legal cases involving labor leaders gained national attention: that of James and John McNamara, charged with dynamiting the Los Angeles Times building, and that of Tom Mooney, a California AFL leader falsely accused of bombing a parade held to support military preparations for World War I.

National organizing and the AFL

For more than a decade, the Robinses moved around the country in order to carry out their political activities. Some of their travels were in a mobile home they called the Adventurer, designed and driven by the mechanically inclined Lucy. An insulated room atop a car chassis, the Adventurer featured running water, bookcases, a birdcage, an aquarium, and a printing press that enabled the couple to print pamphlets and earn money as they traveled.

In 1918, while in Washington, D.C., to urge government officials to grant a new trial in the Mooney case, Lucy met labor leader Samuel Gompers. The brash and articulate woman criticized Gompers for not acting in support of Mooney. When Gompers produced evidence of his behind-the-scenes negotiations with authorities on Mooney’s behalf, Lucy realized that pressure from outside the system was not the only way to solve labor conflicts. She became a lifelong partisan of Gompers and his organization, the AFL.

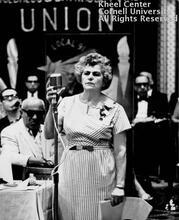

Lucy called Gompers a “philosophical anarchist,” whose outrage at oppression sprang from his Jewish heritage, as did her own. Their common Jewish background forged a strong bond between the two activists. Through Lucy, Gompers gained access to the left wing of the labor movement, including many radical Jewish labor leaders who had openly disdained Gompers’s apolitical unionism. Lucy, in turn, acquired influence among major labor and government figures. On three occasions, she addressed the AFL’s annual convention, one of very few women to do so.

In 1919, she became executive secretary and organizer of the Central Labor Bodies Conference for the Release of Political Prisoners and the Repeal of War-Time Laws. This group spearheaded a national labor campaign to obtain amnesty for thousands of World War I political prisoners, including conscientious objectors, court-martialed soldiers, and those, such as socialist Eugene Debs, jailed for speaking out against the war. Her book War Shadows (1922) documents the successful amnesty campaign.

Later, she became an unpaid, informal assistant to Gompers, and served as executive secretary of the first campaign undertaken jointly by the long-feuding AFL and Socialist Party, raising funds to resist the rise of German fascism. After Gompers’s death, she remained a consultant to the AFL, but at a reduced level of influence due to the increasingly bureaucratic structure of the organization and a less personal relationship with the new president, William Green.

Second marriage and Zionist work

As Lucy became more closely aligned with the AFL, her husband and others with whom she had worked moved in the opposite direction, rejecting anarchism for the communism of the new Soviet Union. The Robinses separated over their political differences and divorced in the mid-1920s. Soon after, she married Harry Lang, a long-time acquaintance and labor editor of the Jewish Daily Forward.

Between 1928 and 1937, the Langs made three trips abroad: to Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Middle East. In Palestine, Lang’s interest in Zionism was stimulated by the efforts of organized labor, women, and young people in national development. Around 1939, she headed a group raising funds to establish Kfar Blum, a cooperative in Palestine for German and Austrian refugees. She continued to conceive of new projects, such as a labor-managed medical center to study, prevent, and cure occupational diseases; but this venture was halted by the United States’s entry into World War II.

Legacy

Despite her refusal to be a paid employee of any political or labor organization and, like many female activists, often working far from the limelight, Lang made significant contributions to American political and labor history. She kept public attention focused on the legal battles of anarchists and labor leaders, and skillfully bridged party affiliations that divided the labor movement. She described herself as motivated more by the plight of individual victims of injustice than by ideology. Yet she never repudiated her anarchist past; in later years, she still called herself a radical idealist and continued to endorse what she considered the fundamental principle of anarchism—respect for the individual.

In the mid-1940s, Lang settled down for the first time when she and her husband purchased a house in Croton, New York. Here, she worked on her autobiography, Tomorrow Is Beautiful (1948). The Langs later moved to Los Angeles, where Lucy Fox Robins Lang died on January 25, 1962.

Selected Works by Lucy Fox Robins Lang

Tomorrow Is Beautiful. New York: Macmillan, 1948.

War Shadows. New York: Central Labor Bodies Conference for the Release of Political Prisoners, 1922.

Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Portraits (1988).

DAB 7.

Gentry, Curt. Frame-Up: The Incredible Case of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings (1967); Goldman, Emma. Living My Life (1931).

Gompers, Samuel. Seventy Years of Life and Labor: An Autobiography (1925).

Kenneally, James J. Women and American Trade Unions (1978).

Mandel, Bernard. Samuel Gompers: A Biography (1963); Marcus, Jacob R. The American Jewish Woman, 1654–1980 (1981).

Obituary. NYTimes, January 26, 1962, 31:2.

Szajkowski, Zosa. Jews, Wars, and Communism (1972).