Stella Adler

Stella Adler transformed a generation of American actors through her understanding of Method acting. Born into a family famed for elevating Yiddish theater to a more nuanced art, Adler quickly achieved star status in her own right. Alder was impacted by her studies of the Stanislavsky Method at the American Laboratory Theater School and traveled to Paris to directly challenge Stanislavsky. Surprised that Americans were using his techniques, Stanislavsky helped Adler rethink the possibilities of Method acting. After returning to America to star in several films and direct several plays, Adler opened the Stella Adler Conservatory of Acting to pass on the new Method, training Warren Beatty, Robert De Niro, and Marlon Brando, and wrote the essential book on her craft, The Technique of Acting.

At Stella Adler’s death in 1992, Robert Brustein wrote in The New Republic, “Stella Adler’s death … represents a major loss in the pantheon of theater greats. Through the strength of her convictions, the integrity of her character, and the brilliance of her mind, Adler embodied the art of the dramatic profession and remained an influential figure throughout a career that spanned most of the century.”

Early Life and Family

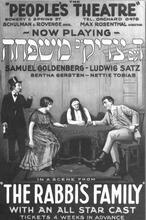

Stella Adler was born February 10, 1902, in New York City, the youngest daughter of Jacob P. and Sara Adler, the foremost actors of the Yiddish stage at the turn of the century. The fourth among five siblings (Frances, Jay, Julia, and Luther) and younger than her known half-siblings (Charles, Abe, and Celia Adler), Adler was enlisted in her father’s troupe as a toddler. At age four, she took the part of one of the young princes in Shakespeare’s Richard III, and at age nine she played the young Spinoza. Her education in New York City public schools always took second place to rehearsals and performances. She played Naomi in Elisha ben Avuya at the Pavilion Theatre in London in 1919, and on her return to the United States had a commercial hit as Butterfly in The World We Live In. In the 1920s, Adler achieved star status on the Yiddish stage, appearing in over a hundred roles in such plays as Jew Süss, God of Vengeance, and Liliom, as well as in classics by Shakespeare and Tolstoy, with the foremost actors of the Yiddish theater, including David Kessler, Siegmund Mogulesko, Bertha Kalich, Keni Liptzin, and Jacob Ben-Ami. There followed a period of time on the road, including tours of Europe and Latin America. Back in New York, she enrolled at the newly established American Laboratory Theater school, where she studied with Richard Boleslavsky and Maria Ouspenskaya, who were then introducing their students to the revolutionary acting technique of Konstantin Stanislavsky. Already a veteran performer, Adler said that the Laboratory Theater, with its roots in the Moscow Art Theater, “opened her up” and gave her a new life.

Early Career

It was at the Laboratory Theater that she met Harold Clurman and Lee Strasberg, who had also come for acting lessons. In 1931, Clurman, Strasberg, and Cheryl Crawford formed the Group Theatre. Their intent was to create an ensemble of players, directors, designers, and writers to produce socially relevant plays that would provide an alternative to commercial theater. To develop true ensemble acting, they decided that everyone connected with a production—playwright, actor, stage designer—had to come to agreement on the meaning and perspective of the play. Strasberg directed the training of the actors based on the methods learned at the American Laboratory Theatre, stressing “affective memory”—the active recall of incidents in the actor’s own life to power her emotion on stage. Clurman invited Adler to join the new theater, initiating a love-hate relationship between the highly individualistic star and the communally committed Group. Although she has written that Clurman was her savior, Adler hated having to submerge her personality into the ensemble, rotating between starring roles and bit parts. Clurman maintained that the discipline was healthy, but Adler felt that the women in the company were coerced into going along with the men. Recalling Adler years later, Clurman described her at this time as “poetically theatrical, reminiscent of some past beauty in a culture I had perhaps never seen, but that was part of an atavistic dream. With all the imperious flamboyance of an older theatrical tradition—European in its roots—she was somehow fragile, vulnerable, gay with mother wit and stage fragrance.”

The earliest members of the group included some thirty actors and playwrights, many of whom went on to stardom, including Morris Carnovsky, Clifford Odets, and Franchot Tone. Elia Kazan joined later as an apprentice. Group Theatre productions, including The House of Connelly, Night over Taos, and Success Story, were highly praised by the critics, and Method acting was launched in the United States. Adler married Clurman, but she split from Strasberg over their differing interpretations of Stanislavsky’s teachings.

Exploration of Method Acting

Despite critical and personal success in Odets’s 1935 play, Awake and Sing, Adler was not satisfied with the Method or with the way her career was going. Taking a leave of absence from the company, she traveled to Europe, where she felt energized by the new theatrical techniques being developed in the Soviet Union. In Paris, she challenged Stanislavsky himself. According to her memoir, she accused him of having ruined the theater. He responded that perhaps she had not understood his method correctly, and (possibly on the strength of the Adler family legend) gave her several weeks of private instruction. Apparently, he expressed surprise that directors in America were still teaching theories that he had abandoned, such as the use of affective memory to activate a role. Adler, reinforced now by Stanislavsky, believed that conjuring up real-life personal tragedies in order to exhibit anguish on stage was “sick.” “Don’t use your conscious past,” she urged the company on her return. “Use your creative imagination to create a past that belongs to your character.” According to Group members, her formal presentation of the revised theory galvanized them and improved their work. Adler now began giving acting classes herself. Her last appearance with the Group Theatre was in 1935, in another Odets play, Paradise Lost

Film and Directing Careers

In 1937, Adler took off for Hollywood, where she made several films: Love on Toast, Shadow of the Thin Man, and My Girl Tisa. Glamorized by the makeup artists and baptized “Ardler” by the flaks, she seemed a long way from the Yiddish theater dramas of her childhood. Later, she was associate producer on several MGM films, such as DuBarry Was a Lady, Madame Curie, and For Me and My Gal. In 1938, she returned to the Group for a season to direct several plays, including the critically acclaimed production of Odets’s Golden Boy, which she took to London and Paris. In the 1940s, she was back on Broadway, taking the role of Catherine in Max Reinhardt’s Sons and Soldiers, as Zenaida in Leonid Andreyev’s He Who Gets Slapped, and as Mme. Rosepettle in Arthur Kopit’s black comedy Oh, Dad, Poor Dad, Mamma’s Hung You in the Closet and I’m Feeling So Sad. She reprised the latter role in 1961, as her last professional appearance.

Throughout the years, Adler was building her reputation as a theatrical director. In 1956, she directed the Paul Green/Kurt Weill antiwar musical Johnny Johnson. She became well known especially for developing the talent of new young actors. Deploring American acting standards, she criticized contemporary actors for not understanding what theater is about. She began teaching at Erwin Piscator’s Dramatic Workshop at the New School for Social Research in the early 1940s. After some years, she left to establish the Stella Adler Theater Studio, where she designed a curriculum that included not only speech, voice production, and makeup, but play analysis, characterization, and acting styles. In the workshops that were central to the curriculum, students improvised or performed scenes before an invited audience of theater professionals. Adler taught her students to build characters out of the material provided in the playwright’s text, within the context of the historical period presented in the play, and motivated by the actors’ imagination rather than by their personal experiences.

Conservatory of Acting

By the 1960s, the renamed Stella Adler Conservatory of Acting numbered more than a dozen faculty and included among its more famous students Eddie Albert, Margaret Barker, Warren Beatty, Robert DeNiro, and Marlon Brando. The latter wrote the laudatory introduction to Adler’s book The Technique of Acting. During the 1966–1967 academic year, Adler was an adjunct professor of acting at Yale University’s School of Drama. The New School for Social Research awarded her a doctor of humane letters degree, and Smith College granted her a doctor of fine arts degree in 1987.

Witnesses to Adler’s workshop performances recall them as the most energetic in New York. Her teaching style can be seen in a video recorded in 1989, in which she exemplifies her own advice to students: “Get a stage tone, darling, and energy. Never go on stage without your motor running.” Filmed in part in her Manhattan apartment, the video presents an energetic and witty woman who looks thirty years younger than her eighty-plus years. Clurman, who went on to become a Broadway impresario and theater critic, describes this apartment in his own video as being decorated in a style that was “part Venetian, part Madame Pompadour.”

Legacy

Adler married several times, the first time at age eighteen to Horace Eleascheff, with whom she had a daughter, Ellen. That marriage ended in divorce. In 1943, she married Harold Clurman, a union that was creatively productive but which also ended in divorce in 1960. Her third husband, Mitchell Wilson, a physicist and novelist, died in 1973. Adler died in Los Angeles on December 22, 1992.

Unlike her older half-sister Celia Adler, who remained in the Yiddish theater, with its roots in Europe and the nourishing soil of the immigrant generation, Stella Adler entered the larger world of the English-speaking American theater. From the older tradition, she brought her passionate attachment to the craft and her profound understanding of the dynamics of the profession, learned at the knees of its greatest practitioners, her parents. American-born and educated, she made the transition to the English-language stage successfully at a time when Yiddish theater was dying. Far from leaving the Yiddish experience behind, she used its strengths to develop her own persona and acting skills, and had the intelligence to modify these through her experience with Stanislavsky. More important for the development of theater in America, she transmitted the new acting techniques to her students and energized a generation of younger actors who shared her passion for the theater

Selected Works by Stella Adler

Awake and Dream. Videorecording (1989).

The Technique of Acting (1988).

“The World of My Parents: Reminiscences.” YIVO Annual 23 (1996).

Brustein, Robert. “Stella Adler.” The New Republic 208 (February 1, 1993): 52–53.

Clurman, Harold. The Fervent Years (1945).

Contemporary Theatre, Film and Television. Vol. 3 (1986).

Current Biography Yearbook (1985).

EJ, s.v. “Adler”.

Robinson, Alice M., et al., eds. Notable Women in the American Theatre. A Biographical Dictionary (1989).

Rosenfeld, Lulla Adler. The Yiddish Theatre and Jacob P. Adler (1977).

Sandrow, Nahma. Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater (1977).

UJE, s.v. “Adler”.

WWIAJ (1938).